Rough Notes and Early Observations on the Blockchain (and art)

Over the course of the last 6 years a strange, almost mystical technology has appeared in our midst, known as the blockchain. Emerging as Bitcoin, a decentralised digital currency, described in a white paper, and unleashed on the world in code by the pseudonymous and now AWOL Satoshi Nakamoto. As this strange bit based currency began to circulate, gain traction and velocity, it’s value seemed to grow almost exponentially, and with it curiosity grew in the underlying technology that was enabling what appeared as a new paradigm of finance. Whilst for the most part the use of this technology has remained an elusive dark art, practiced mostly in strange corners of the internet by the few individuals that possess the desire for a “frictionless” and “trustless” future. But having now recently achieved the acceptance of regulators and investors, the inception of its upgrade; Ethereum, bitcoin 2.0, or “the world computer” in 2015, could signal a change in sentiment. Rebuilt from the ground up and designed as a distributed blockchain based platform focused on planetary scale computation1, smart contracts and decentralised autonomous organisations. Its creation has significant implications for bitcoin’s initial promise of disintermediating nation states and monetary markets. Despite being less than a year old, this platform has already seen the deployment of multiple decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) and decentralized apps. Raising an endless stream of very complicated regulatory questions; What happens when legal paragraphs and mission statements turn into code? What about questions of ownership, jurisdiction and legal liability? Taxes? Subsidies? And what are the latent possibilities for wide scale adoption of code based organisations that are registered nowhere, and available everywhere?

This short text cannot offer you a primer or even a technical understanding of how blockchain in the context of Ethereum works, because that would require it’s own text and others have said it with greater concision, if you’re not already familiar, search now for “Programmable Blockchains in Context” by Vinay Gupta. Instead this is a collation of rough notes, early observations and fragments from a series of ongoing conversations about how blockchain might relate to art, and what might be possible, with a conscious view to remain pragmatic and fairly vanilla about its implications. It should be noted though before these observations are laid out that there are many world altering, difficult to understand, metaphor breaking possibilities currently being built and deployed using the innovations of blockchain technology; decentralised prediction markets, leaderless venture capital funds, identity systems, land registries, immutable file sharing services, sovereign immaterial nations and the possibilities roll on. Speculation and hype is rife, and it only continues to accelerate daily.

With a Nudge and a Shift

Mutual funds, artist run initiatives, cooperatives, these sorts of organising structures for processes of mutual aid and insurance for artist’s futures have existed for a long time. Iterated upon throughout history, from recent efforts to diversify risk like the Artist Pension Trust to the dominant paradigm of medievalism – the craft guild. What’s strange is the relative lack of development in the current moment to produce new supporting or alternative structures for artists to organise and act collectively.

The very basic effect to understand between this in relation to smart contracts (as a blockchain based technology) and the current legal system is in essence usability and access to template-able contracts and executable organisational governance. Writing “Articles of Association” and incorporating a legally recognised organisation can be hard, intimidating and cumbersome.

Clicking your way through a basic mobile application that gives you a functional organisation instantaneously with voting rights, a shareholder structure and the ability to transact payments internationally is obviously going to change things, a lot. (See www.wings.ai)

Taxes and Criminality

Artworks are quite often used as a means to launder illicit funds, write off taxes or completely avoid them. Cryptocurrency can be enormously difficult to track and audit, particularly in the case of off the books exchange of physical objects that are increasingly hidden away in Swiss free ports.

Everyone Hates the Art Market – Bring back the guilds?

Everyone is aware that the commercial gallery system in its current form is struggling to fulfill its traditional role. Simply put; not enough art is being sold to support all of the people that want to be artists, or gallerists for that matter. Add to this that increasingly younger artists are acutely aware that the promotional and platform niche that small galleries once offered has been supplanted by their own use of social media and the ability to interact, connect and be seen globally. The time is ripe for an overhaul and rethink concerning the necessary support structures that are required by artists working today. Whilst it’s obvious that the blockchain isn’t some kind of magical miracle salve that will change this overnight. It is clear that the experimentation in organisational design it offers and will spur, could be significant in causing a sizeable shift to the way in which the artworld industrial complex does business.

Fractional Ownership of Artworks

Basic, obvious and easy. There can be many reasons to share ownership of an art work, collectively produced, bank rolled by a benefactor or a work could be heavily indebted to the ideas of another producer. You can right now produce a paper based contract, signed by all parties, that could (if there was a disagreement) be upheld in a court of law. But this is arduous, legally complicated and can feel like an extreme measure for something that, when produced in the moment, isn’t initially concerned with it’s own commodification. But what if one could bind shared ownership rights to a certificate of authentication produced with a simple application on ones phone? The implications of a basic smart contract that becomes the standard between artists could fundamentally shift the wealth distribution of works that rely on a creative environment at their conception to establish their high auction prices later in life.

Mediation

“For art, the intervention of capital always signals a further degree of mediation. To say that art is commodified is to say that a mediation, or standing-in-between, has occurred, and that this betweenness amounts to a split, and that this split amounts to ‘alienation’. […] The tendency of high-tech, and the tendency of late capitalism, both impel the arts farther and farther into extreme forms of mediation. Both widen the gulf between the production and consumption of art, with a corresponding increase in ‘alienation’.”

Language

The most exciting or most terrifying innovation of the Ethereum platform depending on which way you want to look at it, is the realisation of DAOs, organisations that can run themselves based entirely in code on top of a planetary scale operating system that no one can switch off, due to it’s decentralised disposition. In the film Terminator this is called Skynet – in the world of Ethereum the script keeps changing with each upgrade to its software.

Decentralised Automated Corporations;

Decentralised Autonomous Corporations;

Decentralised Autonomous Organisations;

Democratic Autonomous Organisation.

Accordingly, the acronym for what the DAC/DAO is, can be, should be and is constantly shifting. This is important to observe given that language shapes reality; how people respond to it, which people adopt it and which people reject it will be almost entirely played out based on a reaction to the language deployed. Artists tend to know a thing or two about this.

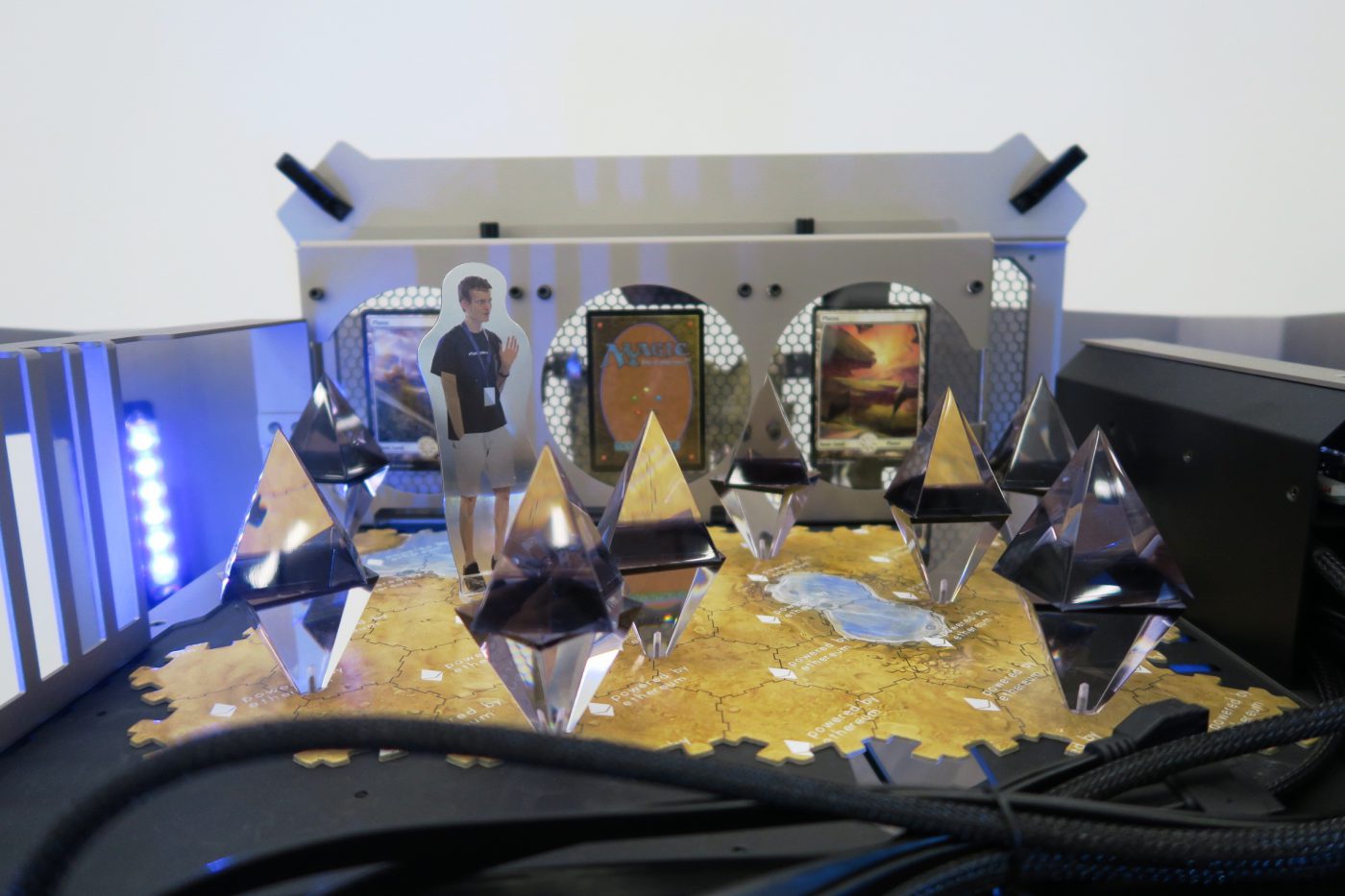

P2P Art Collections

In 2012 I along with a group of artists created a new kind of art collection, which turned out to be more of a force multiplier for individual success than I think anyone had anticipated. Now with these recent programmable developments it could be rewritten in code and replicated. Here’s the recipe we used:

* Start with a group of 5 founding members;

* Each founding member should invite 5 artists to join the collection, these should be artists whom you share an affiliation or respect;

* Thus the collection would discretely represent 30 artists in total;

* Entry to the collection requires only that each artist reserve an artwork and upload an image to a shared Dropbox – these works define the ‘collection’;

* The collection has no public face, it’s existence is intended to travel exclusively via word of mouth;

* Members of the collection are encouraged to extend opportunities not applicable to them to others in the collection – in order to effectively pool all forms of social capital;

* During press opportunities or interviews it would be encouraged that members name-drop other artists in the collection;

* The group should be structured with similar aged artists, to emphasise the invisible hand of a possible new movement;

* Individuals would ideally be distributed between different capital cities;

* Promotion of others work in the collection is incentivised by an equal distribution of profit generated by sales from the collection

* Upon sale of works 10% is retained in the collection fund, 35% divided between the 30 artists, 50% to the individual artist selling, 5% to designated charity.

Note: These observations are not entirely my own, they are merely a collation and structured set of ideas from an incredibly rewarding ongoing dialogue with Ruth Catlow, Vinay Gupta, Kei Kreutler and Takeshi Shiomitsu et al.

1 Ethereum like other blockchain platforms requires distributed computing power to keep it’s network and technology online, at current count there are over 30,000 individual nodes supporting the network. Ethereum refers to this as “the worlds computer”

2 Legal contracts written and executed in code, without the need of 3rd party institutions or expertise.

A Dutch translation of this text was published in Metropolis M No 4-2016 Sharing. Order by email: [email protected]

Ben Vickers

Curator of Digital at Serpentine Galleries, London