A festival on economy, without the economists

What the experts have warned for in the seventies has by now become reality. The invisible hand of Adam Smith has turned into an automated economy, a kind of black box that we cannot decipher or understand. Only the in- and output are aspects we seem to know. Today, after a major financial crisis, no satisfying or viable alternative has yet been set into motion, so we continue on the same foot as before. Economia, a three-day festival in the Baltan Laboratories in Eindhoven, tries to break out of this old way of thinking in order to reclaim economy as a social and cultural construction.

Organizers Olga Mink and Wiepko Oosterhuis invited an international company of activists, artists, filmmakers and many more to re-think and rework economics, without the participation of actual economists. The festival consisted of five threads that ran throughout the program: artists were asked to present their view on the economy, keynote lectures and hands-on experience were meant to de-mystify economics, fictive and non-fictive filmic perspectives were offered, an exhibition decontextualized economy in the arts, and a ‘renewable futures conference’ aimed to invent new avenues. All in all, a packed program of interesting speakers that interwove into a well informed and inspiring festival.

Baltan Laboratories, located in the hip and happening Strijp-S area in Eindhoven, seems to be the perfect place to hold a festival like this, emphasizing the interaction of future thinking, art, and research within an open-minded atmosphere. The former Phillips Natlab harbors multiple spaces, cinemas and an auditorium, where the innovative and experimental spirit of Phillips is still present today.

Within the context of the festival, “the renewable futures conference” focused on pushing the boundaries of thinking about economics. Speakers were divided among different “re-imaginations of economy,” such as economy as magic, game, fiction, or evolution. Rasa Smith Kirsten Bergaust and Lily Diaz, for example, explored the realities of a hybrid economy that consisted of a market-based system: sharing economies, commerce and art. Olga Kisseleva explored another utopia, namely that of a post-oil Kuwait.

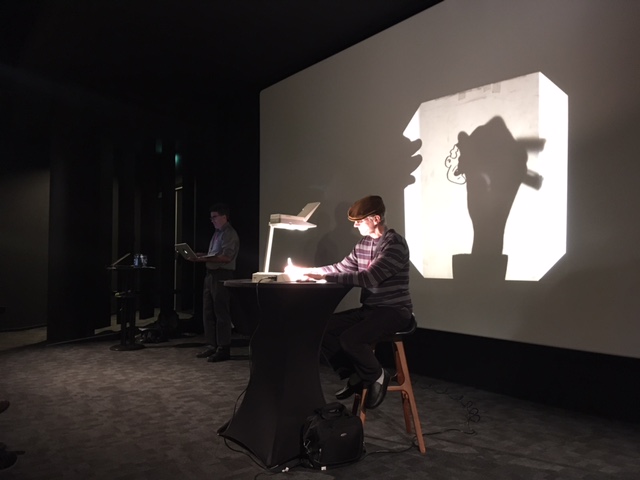

While some tried to explore the futures and utopias ahead, others tried to expose the systems at work. During the three days of the festival, writer Michael Goodwin and illustrator Dan E. Burr focused on the latter. While Goodwin shared his ideas and findings with the audience, a nonchalant Burr visualized these ideas by means of an overhead projector. In one of their daily talks, they explained the complex system of Adam Smith, where everyone’s actions are restricted by the actions of others, so the system continuously adapts to its environment. How does this complex system work? Goodwin and Burr visualized it as a black box, where everyone can see the outcome, but no one can see how it actually works and what mechanisms are behind it. In trying to describe it, they ended up with our world today; where technology reigns and big businesses dominate the economy.

On the second day, keynote speaker Evgeny Morozov, one of the most important critics of cyber-utopianism, spoke about how digital technologies shape our economy and society. Tech companies, especially the four largest ones, have increasingly more power, which has economic and political consequences for our society at large. The market expects that the big companies (like amazon) will destroy the smaller shops, such as your local bookshop. Counter to this narrative, runs the idea that we have nothing to worry about and that this is a revolution with a positive outcome, which justifies a certain lack of anxiety about these developments. What buttresses this positive narrative is the immense flexibility these firms inject into the economy. Something that seems flexible on the surface, such as Uber – where one can be a chauffeur at ones own desirable times -, is sold back to us as something nice. Uber can do this because of their deep pockets, facilitating low prices, contributing to their goal: the destruction of competition. In addition, paying much less or nothing for services such as Gmail, seems like a good deal. But is it really ok that Google scans our emails to show ads? According to Morozov, there is a hidden dimension, which we not yet fully understand.

Every time we use smart technology such as Uber, we train the bots, or algorithms, to become more intelligent. We train the system with every action on the platform. Although this dynamic can make our lives more convenient and efficient, something is happening to our privacy: “data extractivism” is not without its risks. These services, Morozov argues, are contributing to the acceleration of decline of our privacy and autonomy, but all we see is the positive rhetoric of the 70s that these companies want to highlight the most: connectedness and togetherness. Morozov fears that once our governments run out of money, we have little control over how we structure our society, politics and more. Although, he reassures us, ‘this is highly unlikely scenario’.

One alternative approach of data collection and Artificial Intelligence (AI) that he strives for is a democratic one. Who owns the data and how can we take control: re-own our own data? How this could be achieved is still hard to figure out, but what can be concluded from his talk is that the rise of technology, or rather the rise of Big Data, is one of the biggest challenges we are facing today.

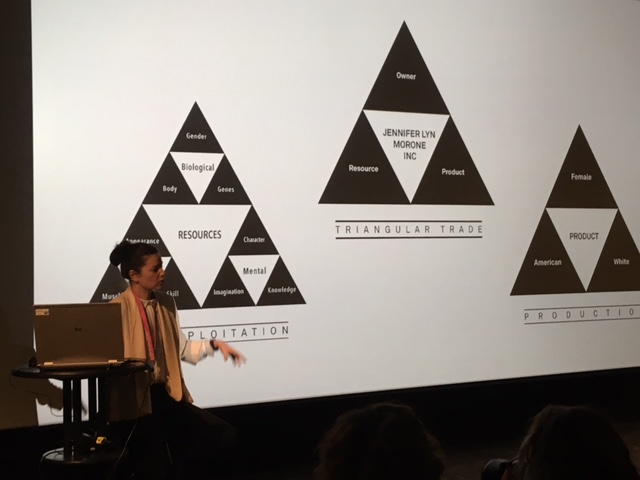

Artist Jennifer Lyn Morone taps into the same themes with her artist talk and work shown in the exhibition. Jennifer Lyn Morone™ (founded in 2014) is a multidimensional project in which she turned herself into a corporation, selling personal data as a business model. Her work deals with the progression of the tech industry and questions the workings of their benefits: their value comes from our information. She tries to determine the value of that information and gets into the mind-set of the system in order to change it. How can the system by disrupted, its public made aware and turned against this fabricated market? How can we get people together in a choreographed moment of disobedience? Her work draws attention to the legal aspect; in a way, we have a contract with the big tech companies, between owner and user, and this should change. According to Morone, we are not getting any money for the motor of technology which we supply: our data. She poses questions such as: How do they use me as a product? And what do I need in return for that exchange? She also makes a reference to Marx, which sums up an important point: maybe we have to go through capitalism to get to the antithesis. Her chart of a new economic model suggests such an antithesis, where the GDP is crossed out, the middleman is cut and profit is shared. What needs to be done is taking re-ownership of building our own future.

A hands-on workshop that deals with these notions of ownership and subversion was led by conceptual artist Paolo Cirio and hacker/activist Brett Scott. The two-day long workshop focused on finance and art hacking, where they guided the participants through the Machiavellian mystery of the finance sector to help them with their own projects, such as the creation of alternative currencies and shareholder activism. The expertise of Cirio, who deals with legal, economic and semiotic systems of our information society, and Scott, former broker and author of The Heretic’s Guide to Global Finance: Hacking the Future of Money, united into a workshop that aimed to expose the elements of finance and jam them. What became clear is that political and corporate players do not act in the broader interest of our (future) society. “We need an economy that doesn’t wreck our ecological stability”. “We need to create equality instead of inequality”, statements, or rather goals that reoccurred throughout the conference. Referring to the tech industry that Morozov talked about, Scott argues that its influence is quite terrifying. Especially the combination of finance and technology has a dangerous potential: it could create a giant panopticon; a world wherein our actions are monitored, almost like a sci-fi dystopian vision.

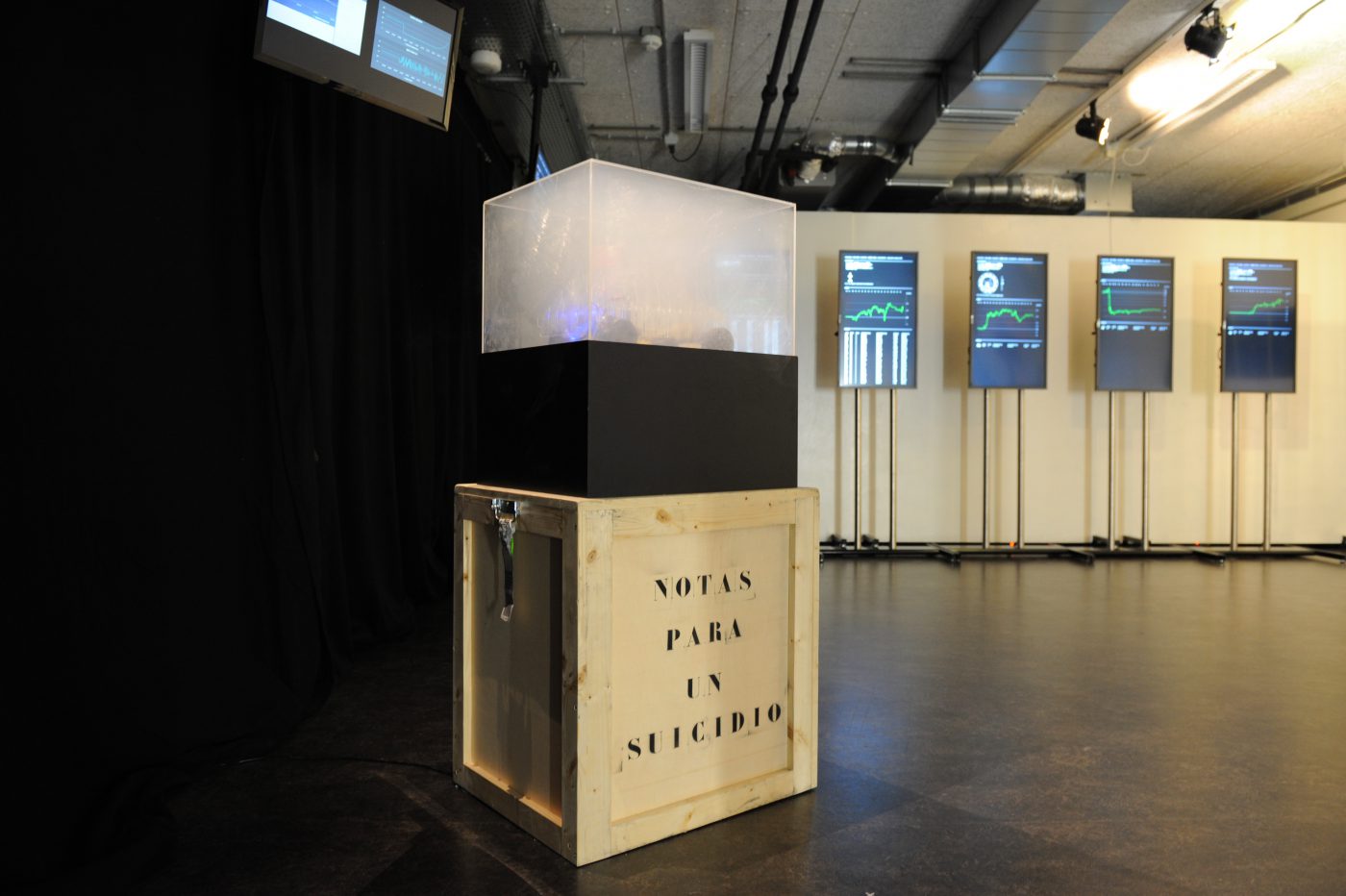

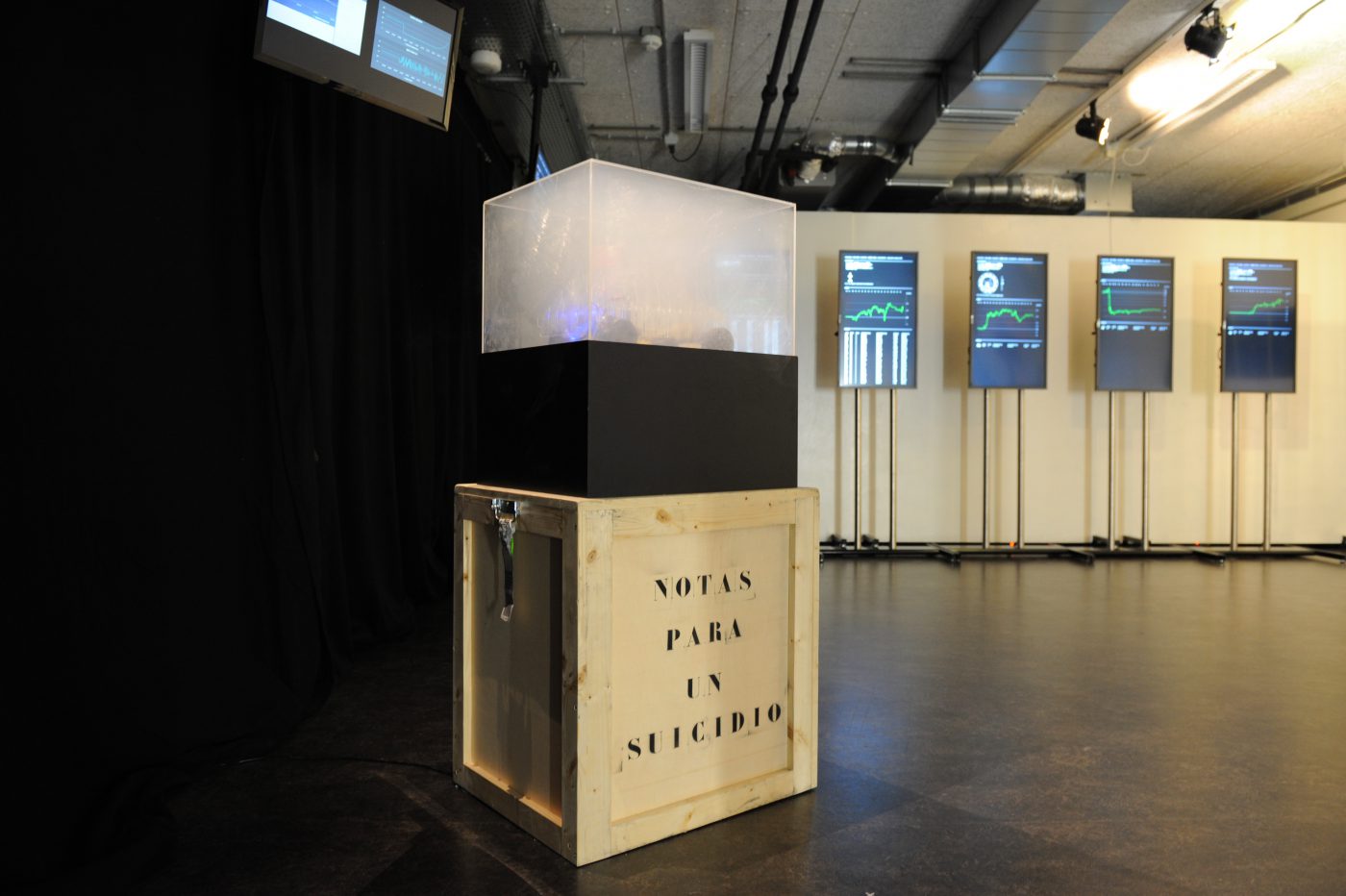

In his work Notes on a Suicide, artist Andrés Costa deals with the aforementioned imbalance between economy and ecology. His installation is composed of a perspex box with a miniature version of a Yugoslavian copy of a Fiat 600 as owned by the artist’s father, connected to a screen monitoring the oil prices and registering the car’s emission. The car reacts to its environment, within the box, and outside and accelerates once the oil prices rise. The installation reflects the world right now. It is the idea of a closed system, where we know the limits of. But above all, the artwork reflects the oil market, and the way in which we base our lives on oil: it is suicide. Costa states that we cannot stop the momentum of our society; it weights too much and we need too much energy to stop it. It is like a snowball that keeps on rolling. We know that oil resources will finish sooner or later, but it is hard to move into a different direction.

What keeps coming up throughout the festival is the problem of inequality, which the invited artists tried to expose by means of deciphering the esoteric markets. It also says something about the position of economy in our society and the ‘financialization of language’, that is one of many symptoms of a deeper contamination. This festival was meant to discuss that, searching for the sources of that contamination, eliminating it, and moving forward in a different way. Economia clearly achieved this objective, by describing and analysing the various aspects of economy, re-thinking it, and re-claiming that which is ours: our own information, our own data, and own futures through a wide variety of cultural, digital and social interventions.

‘Economia’ took place from 28 – 30 April, Natlab, Eindhoven.

More information on the festival, HERE!

Photos by: Diewke van den Heuvel

Corine van Emmerik

is art historian