Overview of the studio of Nishiko at Billytown

Studio visit #1: Nishiko – How to repair an earthquake?

First up in a new series of studio visits (formerly known as studio estafette) Debbie Broekers meets up with Nishiko in her studio at Billytown to talk about the repair project which is currently on view at Stroom Den Haag.

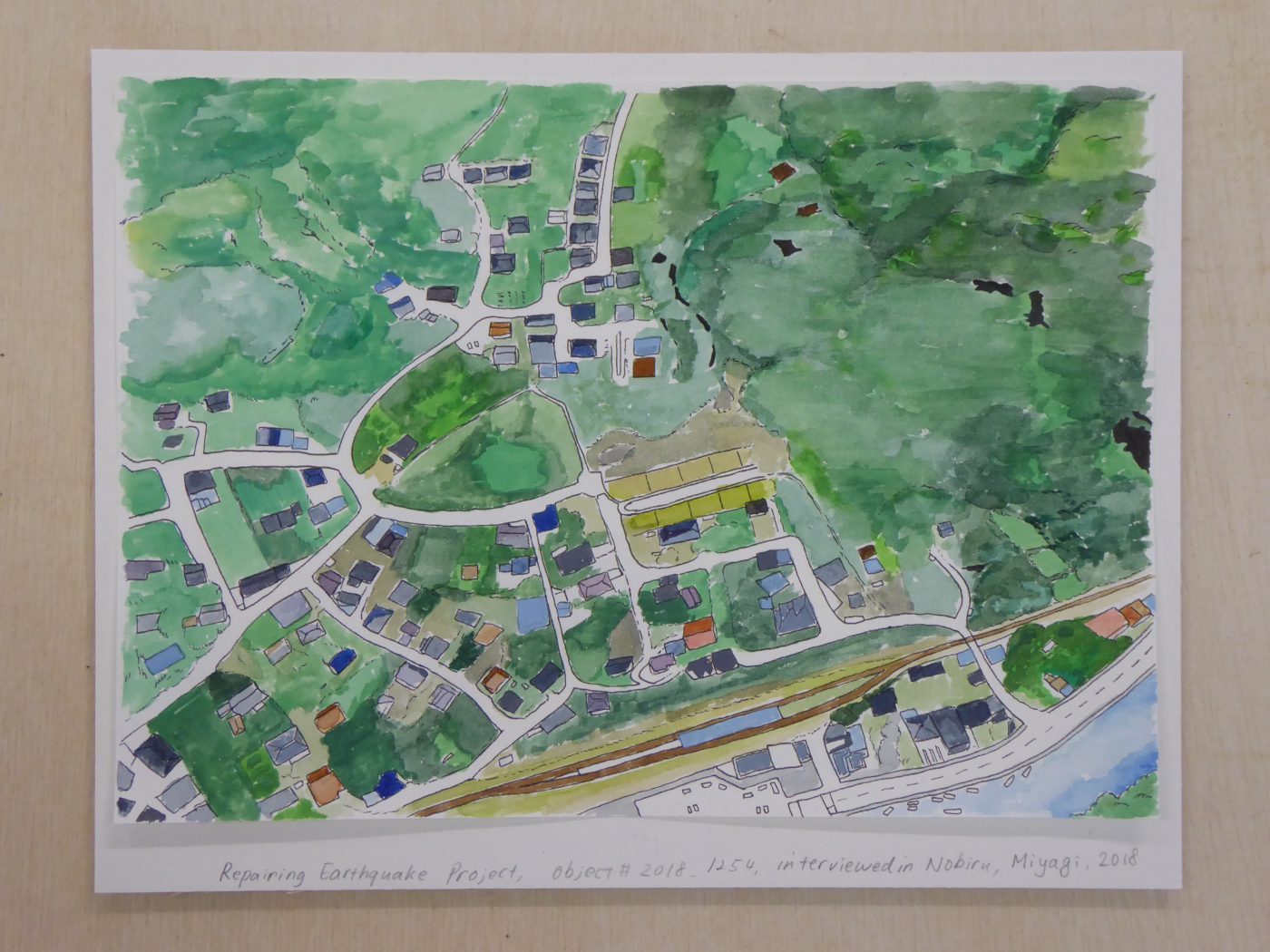

Nishiko (Kagoshima, Japan, 1981) welcomes me into her studio at Billytown with a warm cup of coffee. She just finished her magnum opus project Repairing Earthquake Project, which is currently on view at Stroom. After the earthquake and tsunami of 11 March 2011, Nishiko travelled to Japan’s Tohoku region to look for objects that were left behind in their wake. She wanted to clean and repair them, to find out the stories behind the objects and possibly return them to their rightful owners. They are small gestures aiming to remember a big event. Over the course of seven years, Nishiko collected countless eyewitness accounts and objects both big and small. To this day she continues to look back.

[question Debbie Broekers] Do you remember when you knew that you wanted to go to art school?

Unlike most people in Japan, I didn’t go to university straight after high school. I didn’t know what I wanted to do. So while all my friends continued studying, I got myself a job. My parents live very near the Narita International Airport and I got a job there at the FedEx company, working through hundreds of applications for luggage that people want to import. I worked there for two years, but after one year I started to get bored. Around that time, I started sneaking into the schools where my friends were studying and I got fascinated by advertisement and graphic design. This was a whole field of study, which I didn’t know existed. I didn’t think about design as something that was actually being made by someone. I think that was the moment I knew I wanted to do something creative. Because I was working, I got more financial freedom and started to travel quite a lot, always taking photos. In our house, we had a mac computer with programs like Photoshop and InDesign and I was already using and playing with them. I ended up going to art school in Tokyo, where I enrolled in the photography department, although it was more one class and part of the graphic design apartment. I had a lot of graphic design friends. It was only later, when I came to the KABK that fine art came.

[question Debbie Broekers] So, as an exchange student, you initially focussed on photography?

Yes, but only for the first two days, haha. I knew that the KABK would be totally different than Tokyo because of what my friends from the KABK-exchange program had told me. My work didn’t fit in the photography department, which was totally fine because I was more interested in a conceptual approach anyway. Photography, especially in Japan, is such a closed-off field. So pretty soon I went into the fine art department, which I really enjoyed, because it was completely free! I could do all the things I couldn’t do in Tokyo and people understood them better, I think, so that was really nice.

[question Debbie Broekers] Could you tell me a bit more about your work as an artist? What kind of subjects draw your attention?

For some reason I am interested in the accidental or unexpected moments, when something happens by chance or by accident, that is something I really enjoy.

[question Debbie Broekers] I remember one project of yours that began when you lost a filling from one of your teeth?

Yes! I lost a filling and used the shape as a design for a park. It would be so nice to make that park for real! Those kind of unexpected moments and occurrences were and still are my main interest.

[question Debbie Broekers] Your current studio is a part of Billytown, could you tell me a bit more about this initiative?

Somehow I never seem to remember the actual number, but I believe we are working here with sixteen artists, who all have their studio here. Billytown was founded in 2003 as an artist initiative and I am here since 2011, already for seven years. We also have a guest studio next to mine, where Lennart Lahuis, who currently has a solo show at Fries Museum (Constant Escapement), was working. Billytown is very active and that’s nice. For instance, every Thursday evening we have a weekly dinner where one of us has to cook. I have to say, we’ve got pretty good at it! Downstairs we have two exhibition spaces, the gallery – an artist run commercial gallery which is currently showing the group exhibition 24 kleurplaten and the Kitchen, a project space run by a few artists from Billytown. I’m also running a tiny bookshop there, which was really a dream of mine.

[question Debbie Broekers] Oh! Tell me more about the bookshop.

The Bookshop started at the first Billytown building, but only in my own studio. I started with a tiny bookshelf and called it the Bookshop and that was five years ago already! Slowly books came in and Bookshop grew and now it’s a bit like a shop. I would like to extend and built a proper space for it, though. I just downloaded CAD, so now I can draw my dream.

You need a space to be yourself completely free from all the other things you have to do. It is more a mental space, a bubble.

Overview of studio of Nishiko at Billytown

Overview of the studio of Nishiko at Billytown

[question Debbie Broekers] Since when has Billytown been located in this building?

Since last July, so not that long yet. Since we moved here [Helena van Doeverenplatsoen 3], it has been a bit quiet. A lot of people were away for vacation and the routine of eating together broke. Recently, we’ve started to pick it up again. Also the studios still need a lot of work. To keep it affordable we do a lot of it ourselves.

[question Debbie Broekers] Was it a deliberate choice to have your studio within a larger platform of others?

Yes. I think it’s really nice that Billytown is so active and that you have a lot of active artists around. The flow is positive. Also it is a good place to hang around, I find it really motivating. With other people around, you can very easily discuss and exchange ideas, but also practically, exchange skills.

[question Debbie Broekers] What is the most important aspect of having a studio?

Probably the space itself. You need a space to be yourself completely free from all the other things you have to do. It is more like a mental space, a bubble. I don’t make so many things, I do other stuff in my studio: things for the bookshop, like making shelves, administration etc. Although I don’t really make things, I still find it important to have this space to think.

Exhibition view, Repairing Earthquake Project, Stroom, 2018-2019

Exhibition view, Repairing Earthquake Project, Stroom, 2018-2019

Object from Repairing Earthquake Project

You’ve just finished the Repairing Earthquake Project, a long term project which you started in 2011 in reaction to the devastating tsunami which hit Japan on the 11th of March of the same year. What drove you to make an art project in the context of this event?

There was a lot of discussion among artists-friends from Japan after the tsunami whether or not you could make an art project out of this. One of my friends said that you shouldn’t, and I agreed. I had been working with the subject of accidents for a long time, but I had only been dealing with my own accidents and this occurrence wasn’t mine: I didn’t know anyone there and I didn’t have a relationship with the tsunami-hit areas. But after many people asked or worried about my friends and family in Japan, I realized that I was actually a part of it. Repairing broken stuff was something I had been doing since academy time, so it came together. I think it would have been wrong to create something new. At every step during the project I had to think about ethical questions. When I was there, I had to be very careful in the way I was communicating with people, to avoid takingadvantage of them.

You travelled to Japan’s Tohoku region to look for objects and remnants that were left behind after the tsunami.

In September, half a year after the tsunami, I was able to travel to the Tohoku region with the help of several people. I first contacted Mami Odai, who was then director at Arcus Studio, she introduced me to one of her staff-members who is from the tsunami-hit area originally, who helped me out a lot. Another friend of mine introduced me to one of her friends who could help me out in another region with collecting objects and stories. It was very important for me to talk to the people living there, because I didn’t know what the area looked like before the tsunami, so I wasn’t able to see all the differences and the impact of the event. All these stories, they are incredible.

It must have been very emotional for people to talk about it.

Yes, but I find that people also like to talk about it. This year, in June, I was visiting those two areas and again I asked people about their experience with the tsunami and people said that almost nobody asks such questions anymore, but they seem to be happy to talk about it. The event is slowly fading away. Everyone is moving on and busy with their new life, but sometimes it is good to remember events like this, so you can appreciate the present better.

I like it when there is direct conversation or contact between people and art, or between visitors of the exhibition and the people of the tsunami-hit areas. So I tried to create a place where that could happen.

Exhibition view, Repairing Earthquake Project, Stroom, 2018-2019

Looking back to these seven years, what is the most special or unusual object that you found?

As I write in the booklet accompanying the exhibition, I really like the phone, the t-shirt and the two small plates. I like the phone because it took me such a long time to clean and restore it. I actually had a lot of fun repairing all the objects. I also really like the door, which is the largest object in the exhibition. The door was repaired at Stroom by Johan, a technical guy who eventually brought a door from his own attic in order to repair it. The handle of the Japanese door was still missing and I knew I didn’t have enough time to fix it before the exhibition. I figured that when the handle would function, and you could open and close the door, it was fixed. I told the team at Stroom about the door and said that it would have been nice to include it. The next day Johan brought his own door.

That’s so nice!

Yes! I think that’s how people get involved. The funny thing was that every part of the Dutch door was a little bit bigger than the Japanese door. The hinges, the handle, they are all like 20% bigger. So they were quite busy for a day adjusting the parts to let the Japanese door function again.

Which object was the most challenging for you to restore?

The toolbox. It’s one of the objects I don’t know how to fix, yet.

Yet? The presentation at Stroom marks the end of the project, doesn’t it?

Idea-wise it is complete, but I would like to continue repairing. I thought I would finish the project completely, but when I went to Japan earlier this year, I felt that I couldn’t. I would like to continue visiting the areas, hearing the stories and continue repairing, especially those objects that I didn’t manage to repair yet. Also, I found a new object again. I can’t help it.

You can’t stop.

(Laughing) No, I can’t. This year was the first time I managed to visit a beach which was blocked for years. They made concrete sea walls and now you can go down to the beach and there I found so much debris, it is incredible! I was thinking that it could be that some of the objects reached the other side of the ocean and are now returning.

Unbelievable! At Stroom, you built a wooden platform to present the remnants on. Visitors can walk on the platform and pick up and handle the objects. Why was this important?

That’s how I normally work, so I thought why not? I didn’t think it was special.

Usually when you visit a museum or an art show you are told not to touch anything.

Yes, that’s true. I like it when there is a direct conversation between people and art, or between visitors of the exhibition and the people of the tsunami-hit areas. So I tried to create a place where that could happen. The white cube produces a border between the artwork and the audience, which I don’t like, so I try to remove that again.

In earlier phases of the project you also restored objects on site.

In preparation for an exhibition I did in Mito in 2012, I was discussing with the curator how to present the project and we both felt that it would make sense if I was present there to do the repairs. As it is not about the object, but about the process of restoring and all the stories and people behind the objects. It’s also not about technique. I always tell people: ‘I don’t have a technique’. The conversations are the main thing, so the audience is actually part of it. I also don’t feel as if it is my project, it’s more as if I am a staff member of the project.

At Stroom you were also present at certain moments during the exhibition, right?

Yes, I did some guided tours. Everybody has different favourite objects and people like to hear the stories behind them. I’m amazed by the amount of stories my brain can keep! Next year, I would like to work on the website, to re-organize it, so people can see the objects online and will be able to find more information about them. This will increase the chance that the original owners can retrieve their objects.

Yes, that’s a good idea. You’ve stored the objects with ‘foster parents’ until the original owners come forth. Have objects already been retrieved?

No, not yet. In Mito, it did happen that one of the audience members brought their own object in for a repair. I did repair it, but it doesn’t really count, because it wasn’t an object that I had found myself. But I do feel that some of the objects have a chance to be found since they have some recognizable characteristics and also because I know where I found them. So it would be very good when I could continue to exhibit the project, especially in the tsunami-hit areas, that would help a lot.

Will the objects which are currently at Stroom also be kept by various ‘foster parents’ after the exhibition?

(Laughing) Yes. I have more and more foster parents.

Do you keep track?

Yes, of course! I have to. Luckily, I love working with Excel. It’s a necessary thing of course, to keep track of all the objects, but also when I had to export the objects from Japan to the Netherlands, I had to measure them all, add descriptions, weigh them, pack them, everything! It was a lot of work.

Is there an object that you would want to keep for yourself?

I would like to keep the green vase, which is one of my favourite objects. Although Jane from Stroom also really likes it, so maybe she will take it, that would also be great. I probably won’t give away any of the plastic objects and remnants, since I don’t think I would be able to keep track of them. Besides, there’s no chance that these remnants will go back to their original owners. I also want to keep all the broken objects, so I can continue repairing them, that would be good.

At Stroom you’ve marked the height of the sea level on the window and the height of the highest wave of the tsunami by means of a windsock on top of the building. Downstairs you’re showing two video registrations of tidal movements. As a whole, the presentation stresses the unpredictability and risks of living near the sea. I was shocked to read that we have over 10% chance of experiencing a flood of this magnitude in our lifetime!

We don’t think about these risks nor about the horrible consequences if something like a flood would happen. The difference between a tsunami and a flood, which would be more likely to happen here, is that a tsunami will go away relatively fast, while when the dikes break, you’ll have to block the water and fix or rebuilt the dykes in order to stop the flood. In the 1950s it took peopleover eleven months to rebuilt the dykes. It is really beyond imagining! At the same time, it’s kind of funny and amazing to see that we’re living so far below sea level, the water management system in the Netherlands is really remarkable.

For the last phase of the project, you collaborated with another artist to make drawings of the things people miss the most, drawings of what they have lost. Could you elaborate on this?

I collaborated with Aki Namba, a friend of mine, who is an artist from the same art school in Tokyo. In the past, we’ve often made things together and I thought it would be nice to work with her again for this project. Also, I cannot draw and she can draw very well! Last summer, she came to the Netherlands and for two months we worked on the drawings together. We listened to recordings I had made of all the conversations I had with the people in Japan. She listened to all the of them and together we had some idea of how the object should look like. With drafts of the objects, we also checked via a messenger app or through letters with the people in Japan to see whether the drawing resembled the thing they had lost. They could give their feedback, and we would work on them, so it really felt like repairing.

I noticed in the exhibition that the drawings not only depict personal belongings, but also sceneries and views.

It makes sense, since these views are completely gone now. A garden with a lot of plants and a tree has become a parking space. Nothing remains. These changes feel really weird, so I can imagine that they miss them a lot.

How long does the reconstruction last? When is it completed?

Object from Repairing Earthquake Project

Object from Repairing Earthquake Project

Drawing for Reparing Earthquake Project

I noticed that one of the drawings in the exhibition was left completely blank.

On the last day of my visit, I was taking photos and I didn’t know that there was a guy behind me watching me. He was smoking a cigarette near his house and we ended up having a spontaneous conversation. After a little while, I asked him what he missed the most and he replied ‘nothing’. I think it means that he lost family members or friends during the tsunami and he’s lost. He’s not ready to look back. During my last visit an interesting question came up: how long does the reconstruction last? When is it completed? I came up with this question, because it was so weird to see that all the ‘hardware’ of the area – the houses, buildings, streets – are all brand-new, really brand-new, but there are almost no people.

Object from Repairing Earthquake Project

Like a ghost town.

Yes. It made me think, where are all the people? When are they coming back? Are they ever coming back? And the answer is, they are not. They don’t want to see it. They don’t want to remember. So I guess the reconstruction period will end when new people, who haven’t experienced the tsunami and how it was before, will slowly move in. That will be the reconstruction.

Nishiko: Repairing Earthquake Project, Stroom, Den Haag, on show until 27.01.2019

Debbie Broekers

is kunstcriticus en kunsthistoricus