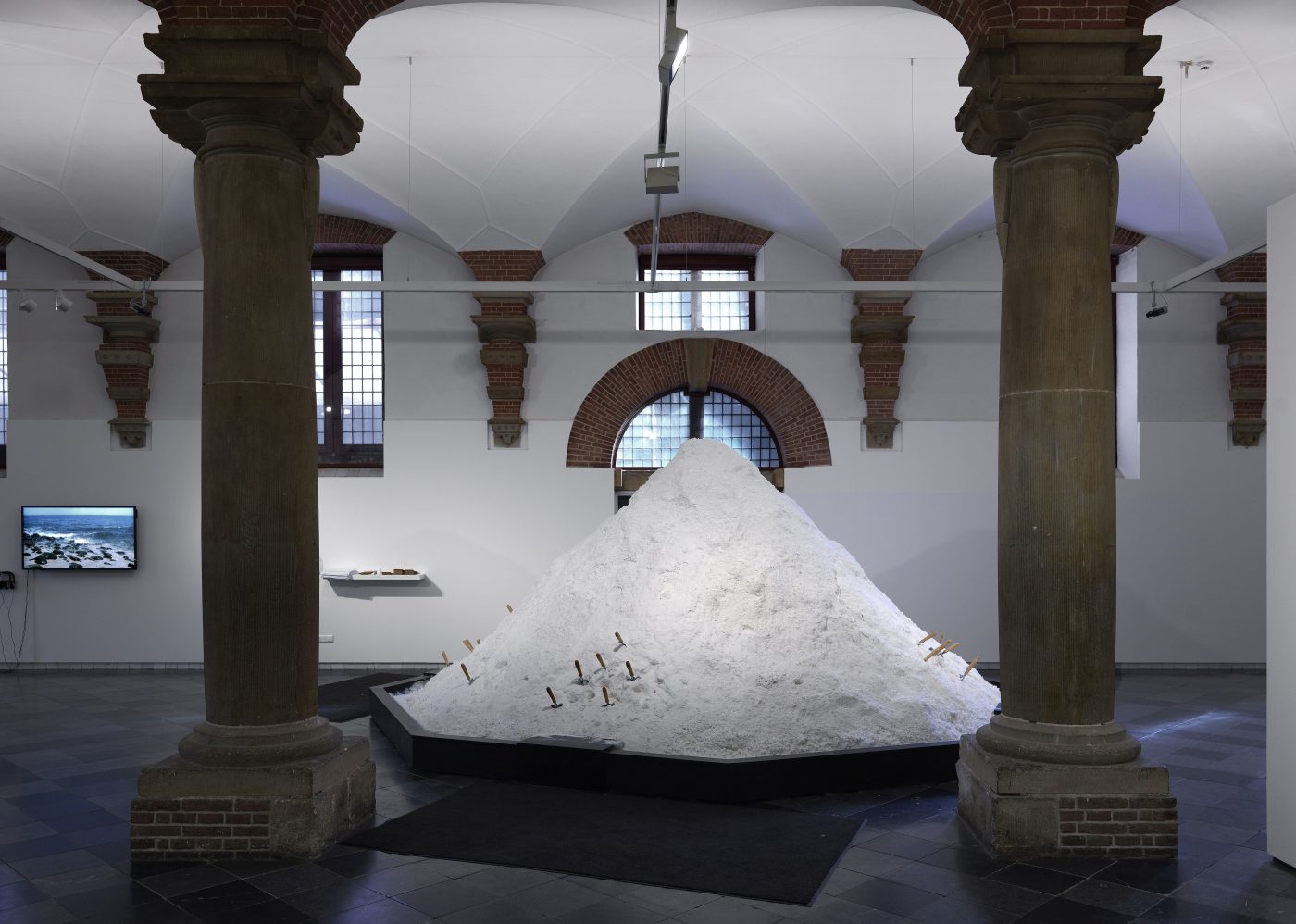

Cooking Sections’ Climavore project on the Isle of Skye. Photo Colin Hattersley

The proof is in the process – Clare Butcher on the art world’s renewed interest in cooking

What makes food fashionable? Art-making processes are moving closer to food-making practices and artists and institutions find inspiration in the global histories of certain ingredients and the domesticity of eating together. Clare Butcher guides us through this development and its merits.

“…perceptions of food and relationships with food traverse the borders of spirit and body. Cooking itself is a holistic exercise…that which you eat enters your whole being,” says Yemisi Aribisala in her book Longthroat Memoirs (2017). Artist Emeka Ogboh proposed that we read the book together at a distance while preparing for a meal in which Ogboh would share his research into beer-making, blending it with histories of the gendered cultural practices of fermentation and spirituality.

This meal and others I’ve recently co-produced with a number of artists, neighbours and communities,[1] have helped me digest the ways in which many art-making processes are moving closer to food-making practices. While this association is not necessarily new – contemporary artists have long tussled with urges to host, to invite, to marinate ideas, to socialise the standard ingredients of the white cube such as seen and tasted in the work of Judy Chicago, Rirkrit Tiravanija and Theaster Gates (to name but a few) – a different smell seems to have entered the kitchen of artistic research in recent years. While before, the relational aesthetics of food-related manifestations may have dominated the dinner conversation, questions of food sourcing, the politics of its distribution, the value of cooking as labour, and the crisis of over-consumption have signalled a change in the menu. Enough food metaphors?

Earlier this year, the exhibition A Global Table – curated by Abigail Winograd at the Frans Hals Museum – brought together a number of Golden Age still life paintings together with more contemporary reflections on the representation of trade relations and traces of colonialism through food and its accoutrements. Patricia Kaersenhout’s The Soul of Salt (2016–), also shown at this summer’s Manifesta in Palermo, was featured in the exhibition and activated by a performance in which the spiritual and ethical dimensions of salt as material and as currency was weighed up. Alongside works by Shelley Sacks, Ellen Gallagher and others, the exhibition offered up not only the material facts of food and its spatial-temporal routings but also the need for more nuanced approaches to food’s role in political boycott as well as the value (and therefore visibility) of certain kinds of labour in different stages of production to consumption.

[blockquote]While before, the relational aesthetics of food-related manifestations may have dominated the dinner conversation, questions of food sourcing, the politics of its distribution, the value of cooking as labour, and the crisis of over-consumption have signalled a change in the menu

Patricia Kaersenhout, The Soul of Salt, 2016 in A Global Table, Frans Hals Museum. photo Gert Jan van Rooij

Interestingly, other than performative moments within the exhibition program, the emphasis of the show did not seem to be on the often messy processes of convening and cooking. Earlier, I alluded to the shadow of relational aesthetics, which may have been the reason for this elision – in recognition perhaps of how “domestic” ways of gathering (in which viewers are transformed into guests/participants and artists into hosts) can quickly become performative exercises or gimmicky forms in which institutions re-brand themselves with shows of inclusivity. That’s not to say that this is the intention of the artists involved in the process per se, but certainly can emerge as a form of soft power used to reduce the historical threshold of the art museum or the experienced exclusivity of art’s over-cooked discourses.

I have to think of a personal example here when I approached an artist to make a meal together as a way of thanking collaborators who’d helped with the production of her project, she was enthusiastic but wanted to make sure that the gathering would be intimate and unspectacular – not instrumentalised by the hosting institution or approached as an “artwork” in itself. The vehemence of her response prompted me to re-think, as an educator, the potential staginess of hospitable gestures which, in a time of great cynicism, can often become just another form of #conviviality. How could historically heavy ingredients be rearranged in order to “consider the fleeting and unpretentious ways of operating that are often the only place of inventiveness available”?[2]

All this is taken into the mix in the ongoing practice of Cooking Sections (duo and self-identified “spatial practitioners” Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe) which marinates in a stew of research, installation, education program, collaboration and para-institutional structure. Their project and publication The Empire Remains Shop (2013–8) departed from the Empire Shops which emerged in the earlier part of the twentieth century in England with the didactic aim of introducing the public to and instructing them in the use of produce from the then British colonies. By investigating “the invention of the ‘exotic’ and the ‘tropical’, shrimp sandwiches, conflict geologies, the financialisation of ecosystems, ‘unnatural’ behaviours, the ecological perception of ‘invasive’ and ‘native’ species, ‘culturally neutral’ food aid, the banana that colonised the world,”[3] and more, the project became a platform for multi-form sharings. Staring with a residency under the banner of “The Politics of Food” initiated by the Delfina Foundation in London, The Empire Remains Shop combined research into imperial circuits and recipes with the experiences and processes of others such as the (Bush) Tea Services of Annalee Davis, a discussion on histories of famine and hunger by Natasha Ginwala, and Midnight Massala performances by Shahmen Suku’s alter-ego Radha La Bia which explored the “limits of bi-racial bi-citizen sexual escapades”.[4] In this sense, the project became a proverbial table around which many living bodies and voices could gather around infamously common histories, chewing over the leftovers of colonial pasts on a personal scale – contending with systems that continue to organize the world in and around us.

It is important however that these intimate ways of gathering around food and cooking up ideas also enter the institution, challenging its organizational logics through which content, community and at the very end of the line knowledge are produced and consumed

Cooking Sections, The Empire Remains Shop, London, 2016. Photo Tim Bowditch

The Empire Remains Shops, The Forest Does Not Employ Me Anymore, Forager Collective, Cooking Sections, 2016, photo: Tim Bowditch

It is important however that these intimate ways of gathering around food and cooking up ideas also enter the institution, challenging its organizational logics through which content, community and at the very end of the line knowledge are produced and consumed. Casco in Utrecht have actively stewarded their access to structural power, material resources and a desire for commonality through the framework of long-term programmes like The Grand Domestic Revolution (created in response to the Utrecht Manifest: Biennial for Social Design almost ten years ago), as well as their current engagement with the Terwijde Farmhouse and the art collective The Outsiders, and focus on Site for Unlearning in collaboration with artist and educator Annette Krauss.[5] The programs created around these convenings are not the easy kind which make for simply inspiring and educational exchanges that help support future funding applications. No. These are unfoldings of the time-taking, emotionally laborious conditions of togetherness which scale down “grand narratives and extreme polemics to destabilizing intimate proportions”.[6] And indeed, this boiling down of social-geo-political complexes to daily, material facts and experiences compels a number of artistic practices which seek to reclaim food and cooking not as ends in themselves but as methodologies for exiting capitalist alienation. A holistic process of thinking with, digesting with, being with.[7]

DIT ARTIKEL IS GEPUBLICEERD IN EEN NEDERLANDSE VERTALING IN METROPOLIS M NR 6-2018/2019. METROPOLIS M KRIJGT GEEN SUBSIDIE. STEUN METROPOLIS M, NEEM EEN ABONNEMENT. ALS JE NU EEN JAARABONNEMENT AFSLUIT, STUREN WE JE HET NIEUWSTE NUMMER GRATIS OP. MAIL JE NAAM EN ADRES NAAR [email protected]

[1] For more details on the context of Emeka Ogboh’s collaboration and the other meals produced with the aneducation programme for documenta 14, see the Nourishing Knowledge programme: https://www.documenta14.de/en/public-education/25659/nourishing-knowledge

[2] Luce Giard, “The Nourishing Arts”, in The Practice of Everyday Life Vol. 2 Living and Cooking, ed. Michel de Certeau, Pierre Mayol, Luce Giard, trans. Timothy J. Tomasik, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998. p.155.

[3] See The Empire Remains project (2016–) website online: https://empireremains.net/about/

[4] Ibid.

[5] For more details see Casco website online: http://casco.art/en/studylines/site-for-unlearning

[6] Sepake Angiama, “Intimacy” in aneducation–documenta 14, eds. Sepake Angiama, Clare Butcher, Alkisti Efthymiou, Anton Kats, Arnisa Zeqo, Janine Armin. Berlin: Archive Books, 2018. p.177.

[7] Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997.

Clare Butcher