Frieze London 2015

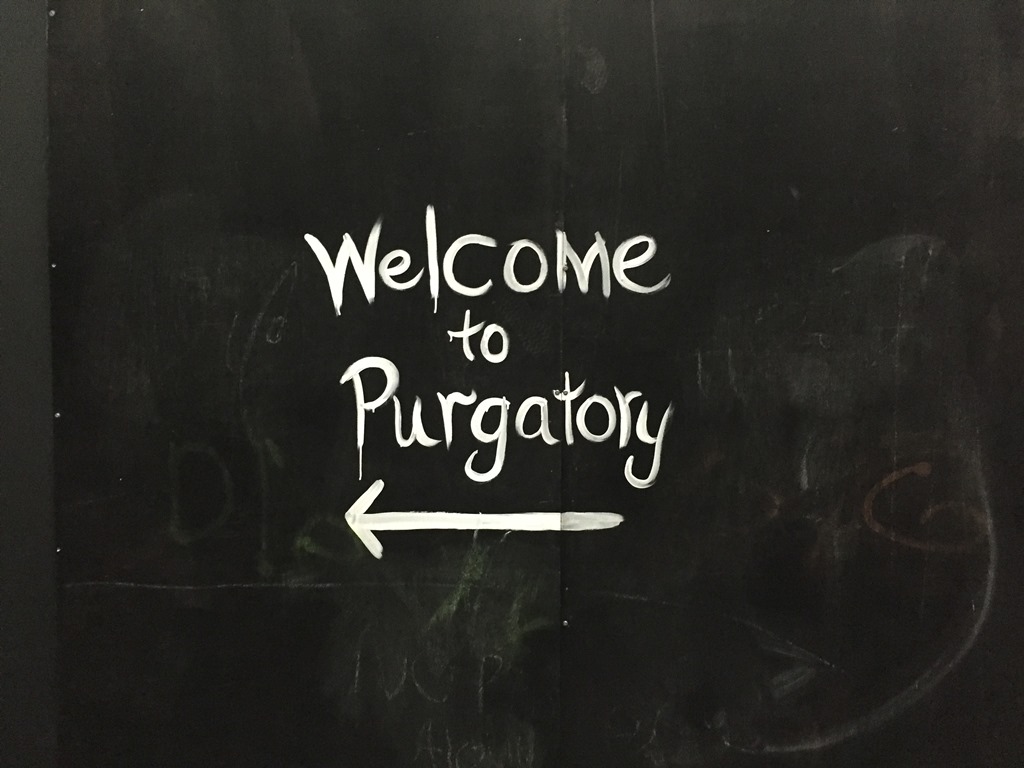

‘Welcome to purgatory’ is painted by Lutz Bacher on one of the blackened corridor walls leading to the entrance of Frieze London 2015. The text seems rather fitting as an art fair could be interpreted as both ‘good’ and ‘bad’. Some would hesitate visiting Frieze Art Fair where money seems to be the golden ticket for privilege and validation. An art fair shows the business of the art world, its purpose is to sell and make money.

Frieze feels more as a catwalk of the rich and famous and a showroom for the art world ‘darlings’; the only time in the year I actually become conscious of my footwear. Indeed, as I was once told by a gallerist, he could judge a serious buyer or collector based on their shoes. How to approach such a vast fair and the quantity of galleries and art works on display? It is difficult to become fully absorbed in the art works on display. No wonder Mark Leckey’s large balloon Felix the Cat at Gallery Buchholz (Berlin/Cologne) has turned into this year’s ‘selfie’ favourite.

One of the first displays that caught my attention was the Berlin/Stockholm gallery Nordenhake showing works by Miroslaw Balka, Meuser, and Florian Slotawa, amongst others. A personal favourite was NCS S 0585-Y80R, a bicycle frame in front of a small red aluminum plate by German artist Slotawa.

In Slotawa’s practice, the artist has been rearranging found objects, transforming them from functional objects to his own material, and gradually started to incorporate his own personal possessions as well – confusing the boarders between art, culture, and materiality. In his new body of work, Slotawa has been integrating ‘found’ colours – shades of auto lacquers borrowed from car manufacturers from the 1980s and 1990s, such as Volkswagen A2Y or Honda BG28P. Through the use of industrial products and commodities as his ingredients, Slotawa is able to transform these day-to-day objects into artistic forms, objects that, through closer inspection, can convey their narrative through their materiality.

Next is Japanese gallery TARO NASU, featuring artists such as Simon Fujiwara and Ryan Gander. As the exhibitors explained, Gander’s Bad Language paintings have been composed of the clichéd designs found on the sides of caravans – a trend that seems to have become an international convention. By reappropriating the symbols into an abstract palette of shapes, the paintings appear as glossy emblems of commercial art, yet deliberately fall down on themselves by borrowing the language of a mobile home.

Alongside are two ‘fur coat paintings’ by Simon Fujiwara. These Fabulous Beasts have been made from shaved second-hand fur coats, revealing beneath an archaeology of skin, stiches, and sometimes manufacturer stamps. [image 8] These furless skins can be read as a raw canvas constructed from abstract patterns, highlighting the struggles between animals and human beings, the poor production countries and the wealthy buyers.

Goodman Gallery (Cape Town/Johannesburg) reveals to the Frieze visitors different aspects of the colonial history through works such as Alfredo Jaar’s neon Culture = Capital, Haroon Gunn-Salie’s Soft Vengeance (Cecil John Rhodes), or Mikhael Subotzky’s Sticky Tape Transfer 13. In the latter, segments of a portrait of a colonial figure and a drawing of an indigenous flower have been transferred by tape onto a third frame, creating a hybrid of the colonial landscape and the white body.

A further critical tone is set by Paul Graham’s solo presentation at Anthony Reynolds Gallery (London), one of the few galleries exhibiting photographic works. On display are the photographic series A1 – The Great North Road and Beyond Caring (1984/85). Beyond Caring depicts slightly miserable scenes taken at British Social Security offices in the 1980s. Even though they were shot thirty years ago, these scenes feel contemporary, reminding one of the financial insecurities felt by many citizens today. These scenes also provide an interesting comparison to Friday’s Frieze Talk titled Can Artists Still Afford to Live in London? – a talk one could have attended after paying the Frieze entrance fee of £36,55.

Amongst the group displays, there were a significant few, such as The Modern Institute (Glasgow) featuring artists such as Martino Gamper [image 13], Simon Starling, Adam McEwan, and Jim Lambie.Another example would be London’s Laura Bartlett Gallery that represented artists such as Nina Beier, Sol Calero, Ryan McLaughlin, and Margo Wolowiec.

This year’s Frieze Projects (curated by Nicola Lees) allow the visitors an escape from the serious business affairs: relax and lie down on ÅYK’s comfy beds for a head massage, whilst providing an alluring ‘charge station’ for your smartphone; take place on one of the tree trunks to hear about the myth of Pan (by Asad Raza); or travel down an Alice in Wonderland-like corridor constructed by Jeremy Herbert, that leads to a space beneath the fair, revealing the tent’s skeleton structure. By installing a wind machine alongside a howling sound, Herbert aimed to introduce a theatrical experience to manipulate the visitor’s physical sensations.

At the opposite side of the tent is an installation by Rachel Rose, winner of the 2015 Frieze Artist Award. She has created a scaled miniature version of the fair’s structure furnished with a soft white carpet, theatre lights, and speakers. The sound and colours change by day, based on the sense frequencies of the animals of The Regent’s Park.

Rose’s structure stands amidst the Focus section where young galleries and emerging artists have developed carefully curated shows and curious installations specifically developed for Frieze.

Simone Subal Gallery (New York) successfully brought together artists B. Ingrid Olson (1987) and Kiki Kogelnik (1935-97) who, despite their generational divide, share a similar approach to the representation of the feminine body. As an active member of the Pop Art movement, Kogelnik translated the features of this male-dominated scene to a more feminist view, exploring the body and the self by deconstructing it, until it became an abstraction of itself. A similar fragmentation is used in Olson’s self-portraits, in which she captures her own body from different perspectives, by fragmenting the image through reflecting surfaces. The photographs are mounted behind framing boards on which additional images have been printed, transforming the board’s neutral space into another fragmented layer of her compositions.

Another artist from an older generation is Stano Filko (1937), who is represented by Galerie Emanuel Layr (Vienna). Throughout his practice, the conceptual Slovakian artist has been fascinated by cosmology to the extent in which he developed his own cosmological system that consisted of five zones, each of which was affiliated by a colour. The works selected from Frieze have been taken from his blue dimension. Interestingly, Filko started to reorganise his work in the 1990s; by revaluating his previous work, the artist renewed many of the dates, altering the work’s narrative and – indirectly – its value too.

One of the highlights is Samara Scott at The Sunday Painter (London). Sitting in the gallery’s floor, Lonely Planet II is a large pool of curious objects and liquids. Oil, fabric softener, kitchen chemicals, fruit juices, flowers, spring union, necklaces, and pens clash together as an alchemic fusion that transforms as time passes, creating a puddle of both growth and decay. Even though her work directly criticises our consumer society and consumer madness, it also voices her own attraction to ‘pretty’ things. Whilst I examine all the different ingredients of the pool, a visitor stamps his foot on the floor in order to film his personally created ripples in the surface.

As I make my way to the exit, I decide to wander through the sculpture park. I come across Jesse Wine’s Let me entertain you (Limoncello, London), a totem-like sculpture sitting naturally in its surrounding landscape. The work is inspired by his father’s fruit-sticks that he used to leave in the kitchen until dried and turned dark. Wine’s enriched his own version with allusions to facial features with god-like creature on top, its tongue hanging purposefully down its chin. It sets a humorous tone; a mixed business with some pleasure that feels rather fitting for the programme of Frieze London 2015.

Adriënne Groen is a London-based curator

Adriënne Groen