Art In The Age Of… Asymmetrical Warfare

Somewhere in the midst of the second and third floor of the Rotterdam Center for Contemporary Art Witte de With, two broadcasts of the 9/11 attacks are continuously repeating images of the most infamous asymmetrical attack in world history. The window on the adjoining mezzanine floor offers a panoramic view of the institution’s roof that is adorned by an abstract blue-white colored shape.

More than mere decoration, it is the crest that prevents the cultural institute from destruction during international conflicts. Upon entering the third floor, screens showing interactive maps of real time cyber attacks make their hallway appearance. While a buzzing sound reverberates on the top floor of the building, the show’s unifying structure resolutely manifests itself: Warfare and conflict are at the heart of this third and final iteration of Witte de With’s year-long focus on the future vectors of art production and circulation in the 21st century.

The exhibition which was curated by Defne Ayas (concept)and Adam Kleinman and Natasha Hoare marks the final chapter of the three-part exhibition series Art In The Age Of… and highlights the role of the artist in imagining the metaphors with which to understand the complex networks of today’s irregular and hybrid battlefield. As is being exemplified by curators Defne Ayas, Adam Kleinman and Natasha Hoare, the theatre of the ever-present war ‘has now extended from the so-called real to the virtual’. Although the physical battle is not eschewed, the lion’s share of today’s war is being fought digitally through cyber attacks, remotely controlled weaponry, social media propaganda and government controlled censorship. As Art In The Age Of… Asymmetrical Warfare demonstrates, the radical shift from the visible to the invisible battlefield asks for an equally radical expansion of its visual vocabulary.

At first glance, this opening up of a discourse is an aesthetically pleasing one. But there is more than meets the eye in, for example, the abstract black, blue and white hues from Broomberg and Chanarin’s The Day Nobody Died IV or James Bridle’s colourful triptych Fraunhofer Lines (MH17 Documents). For the former, the artists embedded with the British Army on the front line in Afghanistan’s Helmand Province. To mark moments of violence, the twosome unrolled a six-meter section of photographic paper and exposed it to the sun. The resulting non-figurative image of the hitherto deadliest month of the war on terrorism offers a powerful form of resistance to the conventional language of traditional photojournalism. In similar indexical vein, Bridle’s three-piece Fraunhofer Lines (MH17 Documents) employs a set of spectral lines to indicate the extent of redaction in documents released by the Dutch government in the aftermath of the downing of flight MH17. Bridle’s abstract visualization of withheld and classified information might not give any substantive answers, yet it raises awareness of the existence of a persistent systematic secrecy within society at large.

Creating awareness is also a strategy for Trevor Paglen and Thomson & Craighead, artists who share serious concerns about the Internet as mediator of conflicts. Thomson & Craighead’s A Short Film About War is made entirely from footage found on the Internet and shows a variety of war zones as seen through the eyes of several military and civilian bloggers. As the ostensible documentary gradually unfolds, a second screen logs the provenance of the images, fragments and GPS-locations that make up the film. The combination of constructed reportage and text logs challenges our perception of the self-proclaimed veracity of documentary by emphasizing how meaning can easily be changed or distorted in the process of mediation. At the same time, A Short Film About War sheds its light on another alarming state of affairs, namely that of today’s privacy-compromised culture in which large amounts of data have become ever-available. It is exactly this circulation of data that is contested by Trevor Paglen’s Autonomy Cube, made in collaboration with Jacob Appelbaum and carried forward from the preceding show, Art In The Age Of… Planetary Computation. The Plexiglas sculpture houses several internet-connected computers to create an open WiFi-hotspot, albeit one in which all of its WiFi-traffic is encrypted and anonymized with the help of Tor, a data-anonymizing network.

Those who hoped for redemption through art could well end up disappointed. None of the exhibited works is going to lead to changes in the system, nor will any of them immediately reduce the number of casualties. Instead, Art In The Age Of… Asymmetrical Warfare gives surprisingly beautiful visual legitimacy to the hidden forces of today’s hybrid battlefield. It reflects the ever growing demand for a visual language that would allow us to understand the complex systems of mass surveillance, military and guerrilla tactics, diplomacy, computation and coding, and of course, weaponry. In this sense, Art In The Age Of… Asymmetrical Warfare presents a promising preview rather than a blissful retrospective – something that seems to fit the curatorial intent of the ambitious series Art In The Age Of… quite well.

Art In The Age Of… Asymmetrical Warfare

Witte de With, Rotterdam

11.9.2015 t/m 3.1.2016

Complete captions

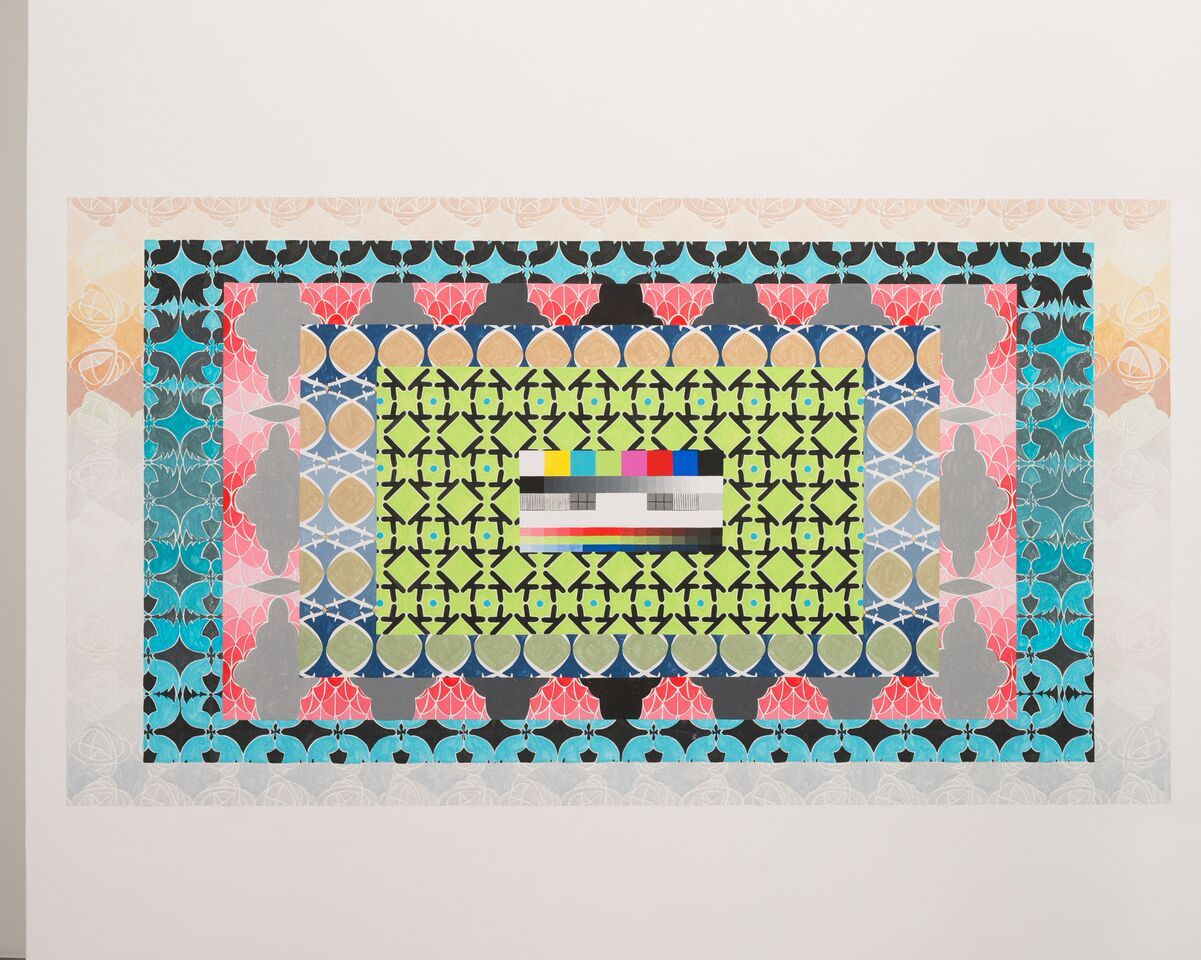

1.

Navine G. Khan-Dossos, My TV Ain’t HD, That’s Too Real, 2015, photographer Cassander Eeftinck-Schattenkerk, courtesy Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art

2.

Trevor Paglen with Jacob Appelbaum, Autonomy Cube, 2014, photographer Cassander Eeftinck-Schattenkerk, courtesy Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art

3.

Glenn Kaino, Now Do I Repay A Period Won (Syria), 2014, photographer Cassander Eeftinck-Schattenkerk, courtesy Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art

4.

Abbas Akhavan, Study for a Blue Shield, 2011/2015, photographer Cassander Eeftinck-Schattenkerk, courtesy Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art

5.

Nida Sinnokrot, Rubber-Coated Rock, All-stars 02, 2015, photographer Cassander Eeftinck-Schattenkerk, courtesy Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art

6.

Sven Augustijnen, “L’histoire est simple et édifiante.” Une selection d’articles parus dans Paris Match, deuxième partie 1973-1976, troisième partie 1976-2014, 2015; Broomberg & Chanarin, The Day Nobody Died lV, june 10, 2008, photographer Cassander Eeftinck-Schattenkerk, courtesy Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art

Manon van den Bliek