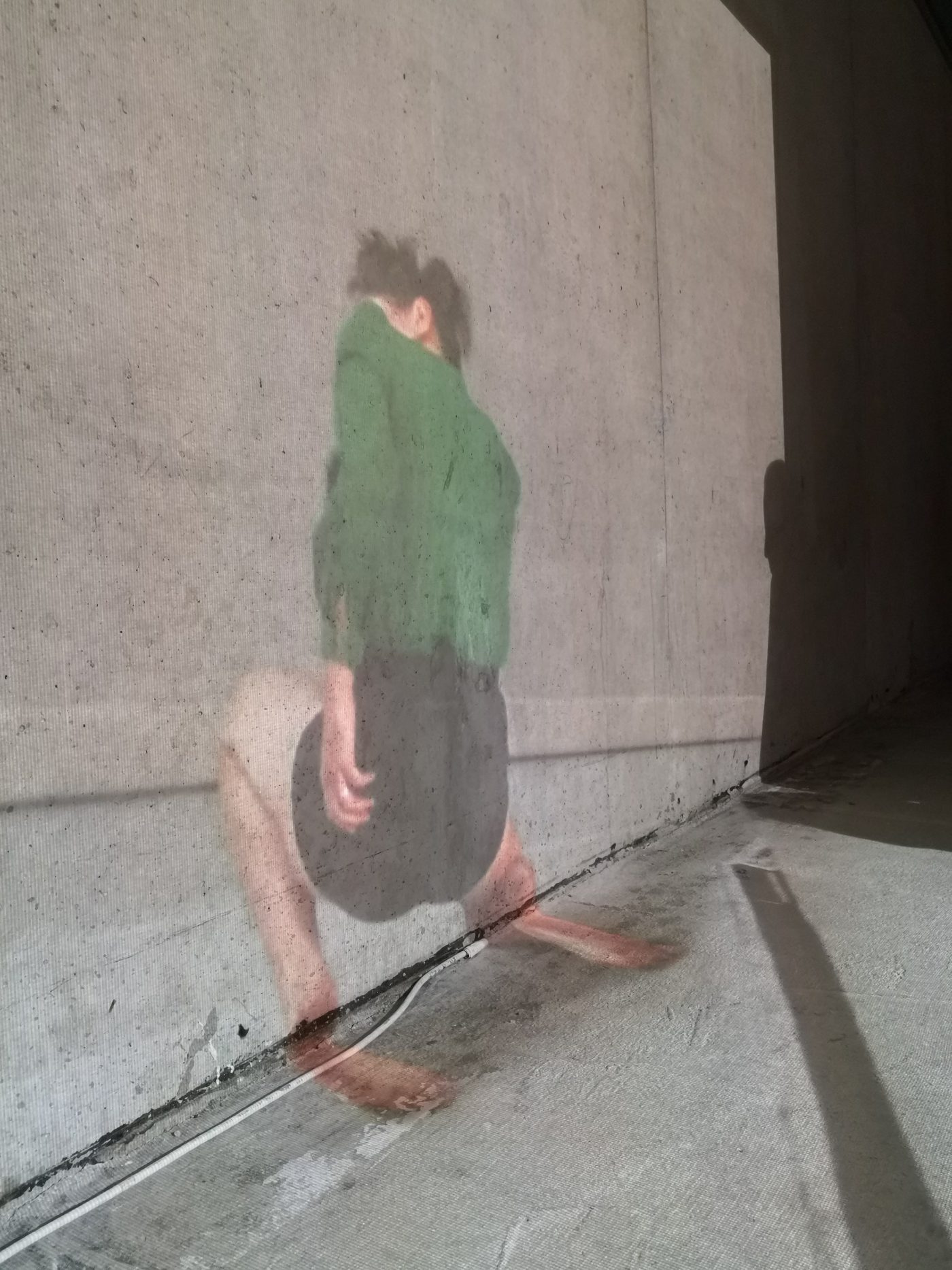

Xavier Le Roy, Retrospective, Hamburger Bahnhof, photo: Dieter Hartwig

Dance and the cube – Xavier Le Roy, 100 Years of Dance and Deborah Hay in Berlin

Dance is everywhere these days. The multidisciplinary and multi-institutional programme What the Body Remembers. Dance Heritage in Berlin therefore asked not what dance does to exhibition-making, but what exhibition-making does to dance.

The multi-faceted, multi-institutional collaboration Was der Körper erinnert. Zur Aktualität des Tanzerbes (What the Body Remembers. Dance Heritage Today) in Berlin explored the question of “dance heritage” through discussion, performance, and a three-part experiment in exhibition making. As we get increasingly used to the format of “dance in the white cube” – or the appropriation of dance and dancers and movement and movers by the visual arts industry – this exhibition program approached the problem the other way around: what promise or problems might exhibition making hold for dance? The distinction was perhaps subtle, but it represented a fundamental restructuring of the power relationships between the disciplines that was remarkable and indeed exceptional.

The project offered three very different examples to consider. First of all there was Xavier Le Roy’s Retrospective performed in the massive hall of the former train station and now museum Hamburger Bahnhof, second there was 100 Years of Dance, an exhibition of relics and videos, and third there was Deborah Hay’s two part project which included the video installation Perception Unfolds and a kind of reading room, The Deborah Hay Documentation Center.

Taking the three examples in order, Le Roy’s Retrospective has in the few years since its premier in Barcelona become a widely renown work, inspiring a whole monograph dedicated to it. (Those particularly interested in the work should indeed take a look at this impressive book.) The work, at first glance, might seem similar to that of Tino Seghal and the format he has popularised: a group of people engage in a series of performative tasks which unfold according to a set schedule, but Le Roy’s work needs to be set apart. Seghal’s work, drawing together the use of ‘scores’ – structures that are the basis for a performance – and the use of a kind of semi-professional performer to make a situation in the gallery – extends from the solution of performance-based artists like Paul McCarthy in using robots and video loops to establish an unfolding situation in the white cube format. Further, Seghal’s unique approach to exploiting auratic presence (probably learned from watching a similar exploitation process unfold in Berlin in the 1990s and 2000s from his vantage point in a squat near Kunst Werke) has now been mainstreamed, for lack of a better word, and is the basis for museums purchasing works of dance like Simone Forti’s Huddle to be made to appear amidst other objects of the permanent collection (interestingly this approach to dance history was left out of What The Body Remembers’ exhibitions).

[blockquote]One could peer behind the rear wall into a kind of back stage space where the performers drank water and checked their emails while waiting for another round, looking up at me pleasantly, with a welcome glance that said after all “we’re in it together”

Xavier Le Roy, Retrospective, photo: Dieter Hartwig

In Le Roy’s work performers repeat certain structures – making a strange buzzing noise as three of the four rush out of the space, or at certain moments gathering to stare at a new arrival into the space, occasionally performing a minimal choreography – a kind of quotation of earlier works from Le Roy’s career – but crucially Le Roy adds a wrinkle to this picture which shifts it, for me at least, entirely. The performers each deliver monologues, sometimes stretching to 20 or 30 minutes, about their own personal biography in movement – enacting key movements – including eventually meeting Le Roy. These candid talks interspersed with movement re-enactments were in some ways like Simone Forti’s later Logomotion work (which has been a huge influence on my work and others) in which embodiment, memory, and narrative unfold in an associative but often highly fragmented flow.

But, unlike in Forti’s work, the narrative flow never broke into abstraction – it stayed strictly prose, not poetry –and in this way it seems as if Le Roy, consciously or not, reached back to the lost world of “performance art” and its dominant form of the monologue and “one person show.” This format – which at one point bridged mass entertainment, stand-up comedy, visual art, and a kind of cultural criticism, made popular in the US by figures like Spaulding Grey, Whoopie Goldberg, Karen Finley, and Anna Deavere Smith was dominated by unpacking social and political questions through the exploration of social construction of identity, a kind of live memoire as case study. The intimate and candid moments of confessional speech in Le Roy’s piece would be inconceivable in the world of Seghal’s “players” and “constructed situations” or the current museum-ified version of Trisha Brown or Simone Forti.

What Le Roy imported into the Hamburger Bahnhof was indeed a key aspect of what German choreographer and thinker Peter Pleyer calls the “culture of contemporary dance”

The day I visited, I stood with Jesse Tuddenham, Contact Improvisation teacher and sometime “player” for Seghal, in a group of three or four people huddled around a young person’s vivid and gripping description of become a professional football player in Brazil, where the job included not just body training in football, but a regime of gender as the female football players were demanded to perform their gender roles with as much commitment as their on-field activities. With a direct mode of address and recounting, eye contact and at times instruction – “you should probably move over here for the next part, as it will need a bit more space” – the boundary between dance and non-dance, a history of movement at the grand (Le Roy – dance/art hero) and the more anonymous was poked at in a way that left us all far more uncertain and implicated than being buzzed at or stared at. What Le Roy imported into the Hamburger Bahnhof was indeed a key aspect of what German choreographer and thinker Peter Pleyer calls the “culture of contemporary dance.”

Drawing back to Steve Paxton, who wondered what meaning his body had when he was on his way to the dance studio with Merce Cunningham, and then developed a way of teaching which facilitated the student into their own exploration and dance which led to “Contact Improvisation,” this culture maintains that the question of the virtuoso and the pedestrian must remain open, and that to reflect on dance history must be made up of those human performances which are both forgotten and full of potential nonetheless. This insistence on considering the broader peopled framework of culture, a non-heroic, non-spectacular-ism, was cemented by Le Roy through the way that one could peer behind the rear wall into a kind of “back stage” space where the performer drank water and checked their emails while waiting for another round, looking up at me pleasantly, with a welcome glance that said after all “we’re in it together.” To me – far more than his mastery of any kind of economy of attention – Le Roy’s impressive accomplishment was crafting a structure which could preserve that living culture into the harsh lights and white walls, by which the question of memory and dance would be raised not as a concept but as a human fact materialised in and with the public, matter-of-factly. As Paxton titled the first presentation of Contact Improv: You come, we’ll show you what we do.

Dance mask of Victor Magito, 1926. On show in 100 Years of Dance, © Susanne Fern, Deutsches Tanzarchiv Köln

The second proposal, of 100 Years of Dance was that if watching videos of dance lacks a quality, it might be made up for with quantity, plus a dose of “production value.” With a starting point in the German dance archives in Cologne, Leipzig and Berlin, through15 small screens and 4 wall sized ones, we were greeted with a mesmerizing unfolding of highly produced video of dance that included many of the famed works of the last decades. With the feeling of an undergraduate survey course, this sprawling presentation – like such a course – offered a tremendous amount to see and learn, but within its claim of expansiveness concealed an editorial process that was highly ideological. In this version of 100 years post-modern dance was a mere stylistic development to be recuperated into the same tradition of ballet, leading elegantly to Pina Bausch’s dance theater. In some ways, this reflects the European institutional structure for dance, in which the black box theatrical convention continues define the field, regardless of critiques of spectacle, virtuosity and the objectification of bodies. The exclusion of Butoh – to say nothing of the recent experiments linking contemporary dance with traditional dance from Africa or new social dance forms like hip hop – said much of the kind of history being told and what the people doing the telling want the public to know. The (mis)representation of Anna Halprin’s Parades and Changes – which includes performers undressing and redressing – summed it up in a nutshell. While the original work – “a ceremony of trust,” as Halprin called it – was performed by not only technically trained dancers but included her children, for this exhibition they selected a slick video produced by a West German ballet company in which the piece seems to have been edited down to only close-ups lingering extensively over young lean nude torsos. It was as if a hippie commune was re-staged by Helmut Newton as MTV soft-core porn in an exhibition on social progress. So with 100 Years of Dance, it was the genre of the ethnographic museum, not contemporary art, that was employed, a colonial gaze that either ignored what didn’t fit in the narrative or transformed reality to match the preconceived vision.

So with 100 Years of Dance, it was the genre of the ethnographic museum, not contemporary art, that was employed, a colonial gaze that either ignored what didn’t fit in the narrative or transformed reality to match the preconceived vision

The most contradictory of the exhibitions was the two part presentation of the work of Deborah Hay. Hay’s work had been presented in different formats in the city from throughout the summer as part of a broader “retrospective,” including a workshop I joined in which Hay guided improvisational sessions with the phrase for which she has become known: “turn your fucking head!” Said firmly with the goal of getting a mover to let go of their preoccupations and re-engage in what’s around them, the whole new world that appears once you break away from tunnel vision, this phrase gives a good impression of a core element of Hay’s work: a non-polite re-engagement of perceiving. “Imagine moving from all of your cells, a million cells” and with “the sky coming into the room, the sky comes in here with us.” To bring this attitude into a video installation – the goal of Perception Unfolds – is a tall task. With four large screens – each dedicated to a dancer in solo – the screens were semi-transparent and so the images doubled on the floor or wall, and the public entering were often both traced in silhouette and also became themselves a screen, so while the solos in the video were engaging and dramatic, and the style of the presentation of the video, it seemed a bit like an exercise lacking purpose. I visited the exhibition with Hilla Steinert, who danced with Hay in Texas, and we both could appreciate the quality of the performances and the novelty of video presentation, but only as distant observations. Reading that the work is itself a kind of experiment in digital media perhaps supplies the missing aim: that of demonstrating new technology to be marvelled at, and the work has that kind of feel.

The most oddly ambitious approach of all was developed by Laurent Pichaud, who sat in the upstairs gallery in the Deborah Hay Documentation Center he organised, he said, precisely because he “did not want to make an exhibition.” Offering the public a kind of mock-up of Deborah Hay’s Texas home, complete with cardboard boxes in one corner and foot paths marked on the floor, a couch with a record player, and a selection of books, the room became a kind of resource for those interested in not being handed culture on a platter, but who wanted to do some digging of their own. A selection of rare books could be read, and a video program played; a few items of clothing hung on a rack and a few letters were presented in a vitrine. Pichaud, whose bio states “collaborates as a dancer, choreographer, assistant, and translator with Deborah Hay,” sat in the corner, as a kind of archival assistant, ready to assist. One was confronted by glimpses of an art which is not so nice, not so polite: on a Hantarex plays a video of a long solo performance by Hay with her face stretched into a shrill smile that breaks into song as she pivots in the space; you hear someone in the public laugh and another sigh. The letters included a reflection by Hay on the need to accept that community did not exist, that after decades of trying to establish community in various forms and places, from dance companies and studios to communes and local government, it was now time to admit the truth and work honestly from the condition of radical alienation.

One was confronted by glimpses of an art that is not so nice, not so polite: on a Hantarex plays a video of a long solo performance by Hay with her face stretched into a shrill smile that breaks into song as she pivots in the space

Installation shot of Deborah Hay Documentation Center at the Akademie der Künste, Pariser Platz, photo: Stefan Hirtz

Of course, only one dedicated to the principle of community would even dare to say such things, and the “Documentation Center” held that promise: a community resource to be offered on the premise that people might need resources. All of the material, Pichaud explained, would soon leave Hay’s possession and go into a formal archive at a university, so they took the invitation as a chance to stage a different public life for the ephemera of a dancer who sees dance as a humanistic category that has not so much to do with visual pleasure. Thus the show was not slick or clever, but demanded interest and commitment and offered an opportunity for serious engagement. In this way, Pichaud and Hay did not just import the “culture of contemporary dance” into the white cube-system, but performed upon that system in the very same unexpected constructive re-working that is a signature of Hay’s work. We did not get lurid postcards from an airbrushed fake commune, nor even a polished art system of dance and memory unfolding, but rather a temporary intervention into that cultural apparatus which rarely considers things like neighbours or citizens, establishing for once a kind of “center.” Many people lingered for quite a while.

LEES MEER OVER DE RELATIE TUSSEN DANS EN TENTOONSTELLINGSRUIMTE IN HET ESSAY ‘TUSSEN RETROSPECTIEF EN REPETITIE: OVER DANSTENTOONSTELLINGEN’ DOOR ROOS GORTZAK IN Metropolis M Nr 4-2019 – Ziektebeelden, Het Grote Micro Art Initiatives Onderzoek. ALS JE NU EEN JAABONNEMENT NEEMT, STUREN WE JE DIT NUMMER GRATIS TOE. MAIL JE NAAM EN ADRES NAAR [email protected]