Back to the Future David Maljkovi?

There is a mysterious atmosphere in the work of Croatian artist David Maljkovi?: monuments from the history of modernism are exposed in videos and deployed anew in what appears to be an homage to the future. With his current exhibition in Eindhoven, Maljkovi? also seems to be increasingly applying this procedure to his own work and to the exhibition itself, an attempt to shed new light on it.

At the center of David Maljkovi?’s work is a scenography informed by an ongoing engagement with the legacy of modernism and modernity, including the eventful history of his native Croatia, and a uniquely hybrid approach to both narrativizing and emptying out the expectations of display and projection. Constructing speculative histories via glimpses onto overlooked moments of past innovation, Maljkovi?’s sculpture, collage, painting, drawing, and architectural mise-en-scène often refer to the historical backdrop of socialism and the aesthetics of international modernism even as they frame his own versioning of impoverished science fictions and depleted allegorical tableaux. By continually mining a rift between the utopian aspirations of former avant-garde strategies and their frequently cataclysmic results, Maljkovi? gives the equivocal nature of our present moment a spectral shape, his work existing in a register of potential renewal and perpetual failure.

An acute awareness of the experience and conventions of museological display and exhibition design grounds Maljkovi?’s entire oeuvre and contributes to the wry retrospective mode of his recent work as he retraces his own practice, moving through and re-animating frames and display devices from his own past exhibitions and artworks with equal measures of calculated remove and hyper-sensitivity.

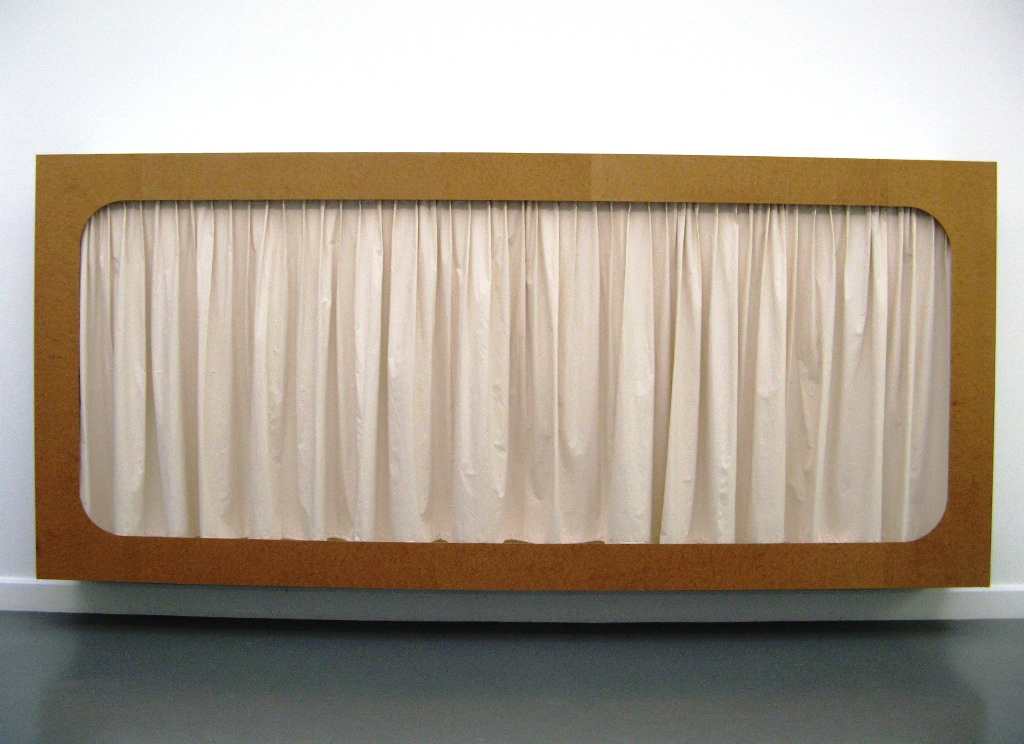

Objects previously developed and designed to house or display explicit content – ephemeral, fictional, and historical – have been left nearly void and overtly gestural. As with his recent show Exhibitions for Secession (2011-12), at Secession in Vienna, the act of exhibiting itself takes on an affective register that evades a subject and becomes the primary focus of the viewing experience. As Maljkovi? himself describes in an interview accompanying the exhibition, ‘The project is conceived in a way that rids itself of content and isolates the set-up itself. The retrospective attitude does not pertain to the works themselves but to the sum of set-ups from various exhibitions.’1

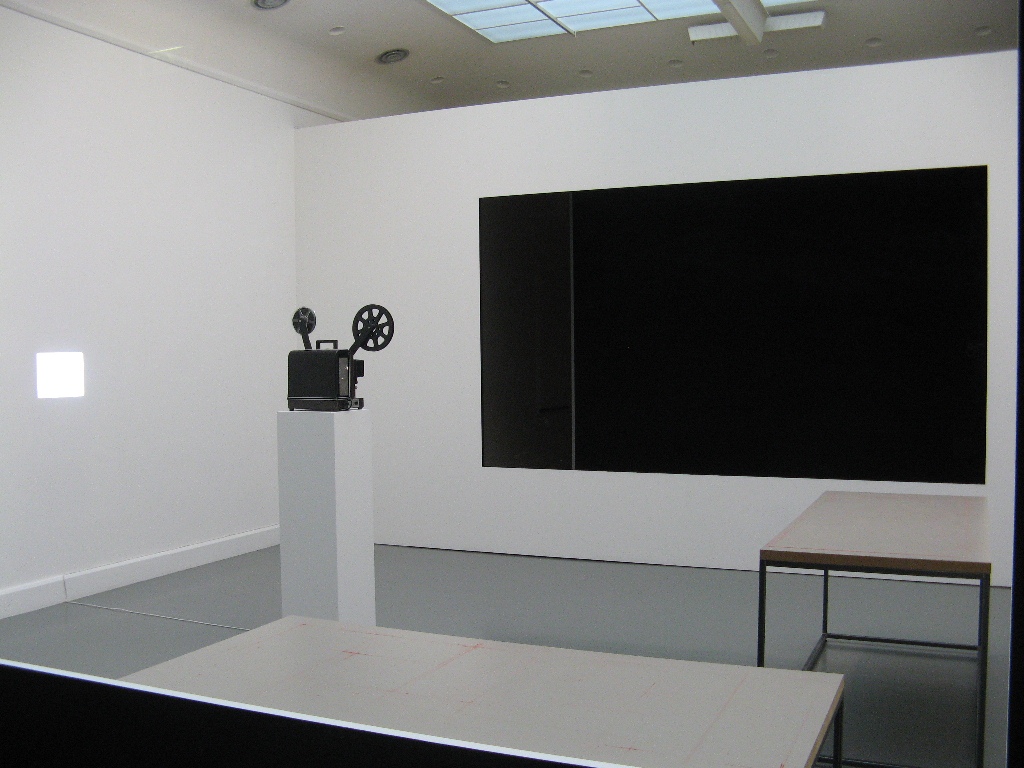

Informed by this recent emptying out and uneasy revision, Maljkovi? is producing alternate exhibition versions for his mid-career survey set to open at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven this fall before traveling to BALTIC in Gateshead, England, and GAMeC in Bergamo. Intensifying his longstanding collaboration with Zagreb-based architect Miroslav Rajic, Maljkovi?’s designs include an initial show in the Netherlands designed for sequential galleries, followed by a co-habitation in a single space where the works themselves obstruct and partition the viewing experience, and a final compression into a scenario focused on projection and cinematic simultaneity. While the version at the Van Abbemuseum will include signature earlier works, including his video trilogy Scene for New Heritage (2004-06), a more recent sculptural work reveals both contrast and continuity with perhaps Maljkovi?’s signature early work.

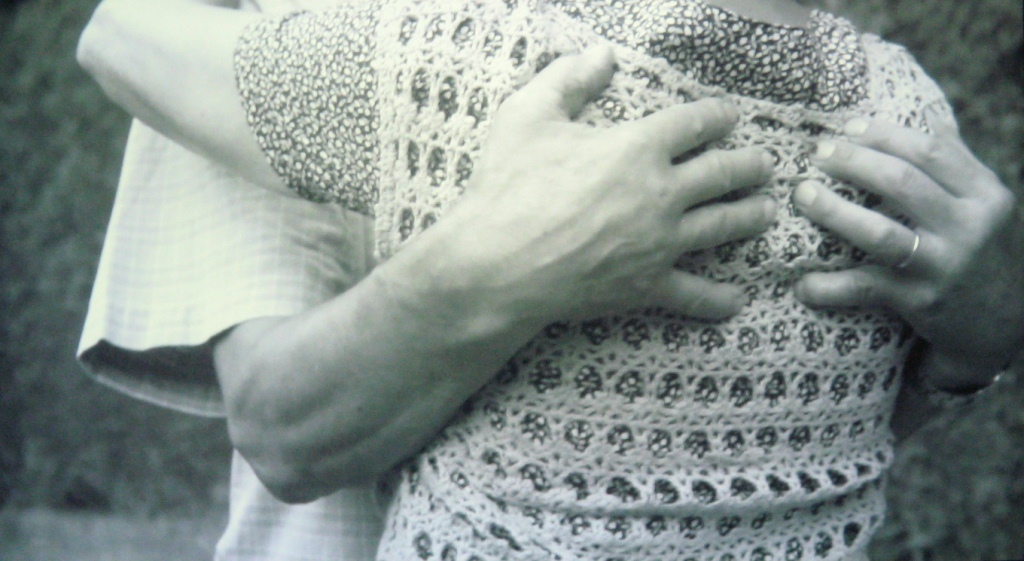

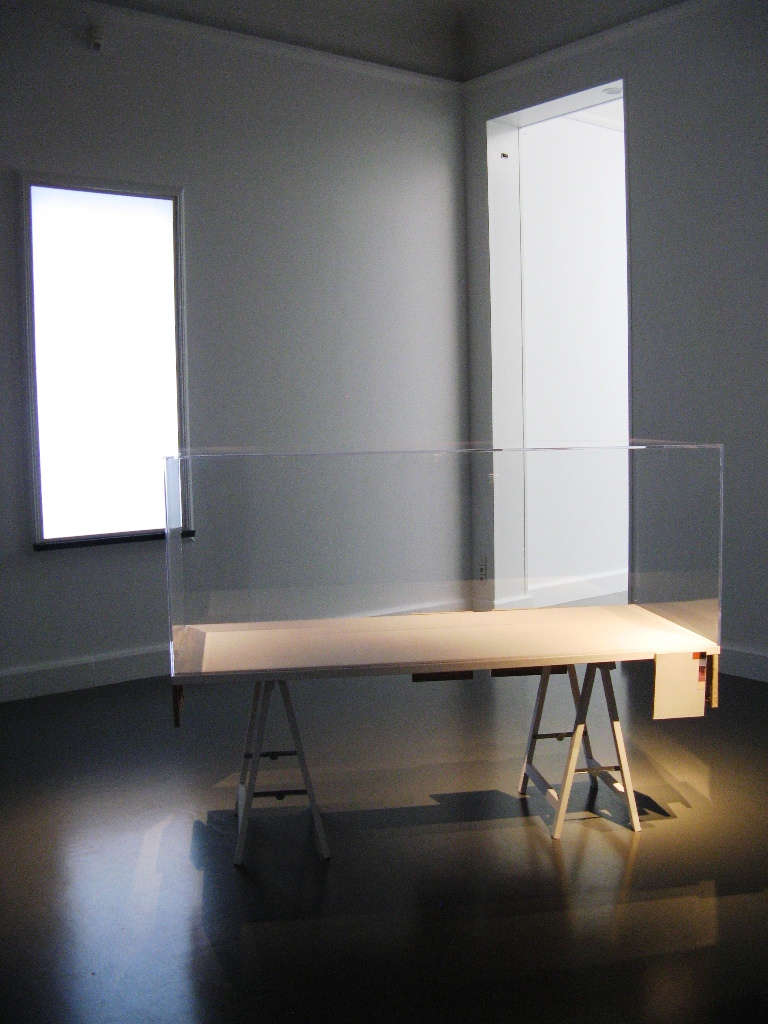

Sources in the Air (2011-12), shown in various iterations over the past two years, features collaged canvases hanging from the exterior of an empty Plexiglas vitrine resting atop customized white trestles. Kept peripheral, the collages offset the encapsulated time and the enclosure of bound artifacts or fetishized art objects implied by the museological display structure and immediately recognizable Minimalist trope. A montage-like sequence of black-and-white photographic fragments are partially draped and offset by swaths of multi-colored, cotton cloth obstructing and adorning each canvas; partial gestures, the photographic fragments show hands placed protectively downward, a facial gesture obscured to reveal only the blank geometry of tie and blazer, more hands clasped in an embrace, arms crossed in observation, or a woman in bureaucratic attire visible from behind.

The act of inspection, stepping closer to see what indexical specimen, rare artifact, or odd vapor lies within, what ephemeral documentation awaits, is re-deployed by Maljkovi? as the vitrine takes on its second contour of architectural model. The parceled-out, less-than-enough gestures of the photographic fragments greet the viewer with a sudden inversion of scale. The expectation of reading evidentiary material or encountering a coy dematerialization (à la Hans Haacke’s Condensation Cube, 1963-65) is replaced with an observing yet withheld stance – the object itself looking past the viewer’s desire to witness a captured phenomena or fixed references and historical settings.

Taken from a book published in the 1970s during Josip Broz Tito’s authoritarian rule of a Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the collaged images are culled from a chronicle of the International Congresses held in Yugoslavia. Maljkovi?’s sources are exposed and made vulnerable here, precariously dangling outside the conventional place of legibility and context. Further inspired by avant-garde artist and architect Vjenceslav Richter’s design for the Yugoslavian Pavilion of the 1958 World’s Fair held in Brussels, Belgium – which was initially referred to as ‘foundations in the air’ – Maljkovi? merges vestiges from two distinct utopian moments (political platform and design fair) into a succinct yet bracing and observant gesture. The big, empty Plexiglas cube evacuates planning and modeling for a socially engineered future. In doing so, content and form are displaced but also made directly available to the primacy of looking again and re-reading. The contour of what appears initially familiar retreats into a recalcitrant gesture of being less than enough to read past aspirations for the future.

What initially seems a vastly different encounter of too much in Maljkovi?’s video trilogy Scene for New Heritage (2004-06), undergoes a similar choreography of depletion and gradual refusal. Perhaps the artist’s most widely known work, the three videos inhabit the site of Petrova Gora Memorial, a futuristic yet derelict monument to the Yugoslav partisan victims of World War II, completed in 1981 by artist Vojin Baki? (1915-1992). Constructed near the former site of a partisan field hospital, the memorial was commissioned by Tito’s government and intended to be part of a regular itinerary for patriotic citizens and the youth of Yugoslavia. Left in a neglected, ruinous state following the intense violence and turmoil of the Yugoslavian civil wars of the 1990s, the failing structure becomes the setting for three short speculative scenes on the part of Maljkovi?. Featuring young protagonists attempting to come to terms with the overt yet receding symbolism of the futuristic metal-clad monument, Maljkovi? sets the episodes in a near future, 2045-2063, borrowing the tropes of science fiction novels and films.

In the fast-forward scenario of the trilogy, the monument is quickly transformed from an object of initial effrontery and curiosity into one of backdrop and distraction. As Maljkovi? describes it in an interview, the starkness of Baki?’s tower sparked an epiphanic shift: ‘I don’t know how I found myself in that place. Probably the unconscious again directed the course of my journey. I only know that I stood looking at the sight of the monument for a long time. Suddenly I succeeded in finding a narrow slit to escape from all these historical facts and the journey started. I returned to the future and was in 2045 on the 25th May. I followed a group of people who set out in quest of their heritage and everything seemed without pressure; history became an issue of fiction, and time created a collective amnesia.’2

A release of historical pressure, a letting go of barriers and a mingling of time and space, the initial video portrays a group of young men approaching the glinting monument up on a plateau. With their emergence from a tinfoil-covered automobile to awkwardly inspect and literally sing in a forceful folk dialect directly at the metallic structure, the video is both solemn and comic. Featuring a foreign icon imbued with weakened symbolic power, the first video quickly gives way to the second winter scene of a solitary young man arriving to scale the monument and look out over the blankness of a snow-covered landscape. For the final scene, groups of teenagers hang out and socialize with seeming indifference to the setting.

The ritual time of memorial has been incorporated and merely invokes a meeting place, a backdrop with no particular significance but a distinct atmosphere. Incisively compressing a process of cultural forgetting deeply seated within the aesthetics of Modernism, the trilogy moves from the typology of an archaic encounter, through the poignancy of a coming-of-age moment of individuality, before ending with a final scene of ‘collective amnesia’ where the drama of the monument’s formal excess is re-directed, appearing as if it were nothing more than a digitally rendered background for a prospective advertisement.

And yet the status of Voijn Baki? as an exemplary modernist venerated for breaking away from the styles of Socialist Realism toward an expressive abstraction is more than simply a footnote to Maljkovi?’s interest and approach to heritage. Viewed by some as a ‘state artist’ due to the many commissions he received, the style of Baki?’s work remains uniquely open to speculation here. Citing both Futurist impulses and a neo-Constructivist style that is both nostalgic and self-aware, the cultural terrain that Maljkovi?’s work collapses via Baki?’s tower is fraught with ambivalence, as he does not seek to redress or correct the past but rather insist upon its atavistic possibility as a setting worthy of renewed questioning. Including the Petrova Gora Memorial as an uncanny presence and likewise an object to be refused, Maljkovi? develops here a dual treatment of cultural heritage ‘as pregnant with all the unrealized commitments to experimentation and collectivism beyond any particular case, making the present fundamentally open to the risk of new meaning,’ according to the collective What, How and For Whom.3

Indeed, for Maljkovi?, strategies from the Yugoslavian avant-garde are repeatedly held within a process of becoming. As the receding, concentric-like structure devised for viewing the trilogy’s projection in recent exhibitions suggests, Maljkovi? maintains the initial vertigo of the circular ascent that hits a visitor upon entering Petrova Gora. The stratification of the past imbues the display and set-up.

Images With Their Own Shadows (2008), for example, is set in the villa and former studio of the influential sculptor Vjenceslav Richter (1917–2002), a member of the EXAT51 group of experimental artists and architects.4 Maljkovi? layers sound clips from Richter’s last interview with a highly suggestive tableaux vivant of futuristically attired young people poised before EXAT 51 models and sculptures. Their open-mouthed attempt to communicate is made halting and incomplete. They are unable to speak. They cannot complete the translation from the past. Richter’s many arguments for the political freedom inherent within abstraction and experiments between the applied and fine arts are evoked but also suspended by Maljkovi? – becoming an allegorical gesture to reconsider and temporarily inhabit.

While a subtitle proclaims Richter’s belief that ‘as long as there are studios that experiment, EXAT has not ceased to live and work,’ the visionary resolve of the group is made into a contingent rehearsal. EXAT 51 sculptures are shown and demonstrated for the camera and the entire projection is held within a sculptural frame that further removes the viewer. The tenets for future innovation are present but diminished, reverberant but stalled, echoing within Maljkovi?’s architectural sequencing like a lost language.

Credos of innovation and prototyping undoubtedly continue to moderate present markets and economies, but for Maljkovi? such rhetoric spurs contingent, participatory gestures that delay and fail to prognosticate. Speculative forms are only present in concert with embodied and indebted evocations of the past. For Out of Projection, 2009, Maljkovi? filmed in black-and-white at the carefully guarded test track of Peugeot’s headquarters in the French city of Souchaux, casting retired company workers in out-of-time gestures of embrace and observation alongside the most current automobile prototypes. The aging human bodies of the retired men and women look on beside the test track, pose in still sequences alongside futuristic vehicles, and repeatedly embrace in choreographed gestures that recall Giorgio Agamben’s description of the re-animating principle of film and its central dynamic of projection: ‘In the cinema, a society that has lost its gestures seeks to reappropriate what it has lost while simultaneously recording that loss.’5

As with the advent of cinema and the art of projection, the test track and its illusory promises of ever-advancing speed and efficiency are enfolded into Maljkovi?’s stratification of modern temporality and super-imposition. An echo of titles arises from the void yet oscillating forms at Secession, indicating their most recent iterations, Lost Pavilion (2008), After the Fair (2009), Retired Form (2009), A Space Happened (2000), and Missing Colours (2010), and Maljkovi?’s narrow escape comes clear: projection issues us backwards into an aphasic present, while rehearsal returns us to looking again, to recalling the frames here before us.

Fionn Meade is a writer and curator based in New York. He is faculty in the MFA Program for Visual Arts, Columbia University, and in the MA program at the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College.

David Maljkovi?: Sources in the Air

Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

6 October 2012 through 27 January 2013

Notes

- David Maljkovi?, ‘Prologue’, Exhibitions for Secession (Vienna: Secession, 2011).

- Yilmaz Dziewior (ed.), Almost Here, exh. cat., (Hamburg/Cologne: Kunstverein Hamburg and DuMont, 2007) p. 26.

- What, How & for Whom Collective (WHW), ‘This is the 11th International Istanbul Biennial Curator’s Text’, exh. cat., 11th International Istanbul Biennial: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (Metinler, 2009) p. 105.

- A founding member of EXAT-51 – short for Experimental Ateliers – Richter was part of a group of Croatian artists and architects active in Zagreb between 1950 and 1956 whose work called for the legitimacy of experimental art practices, and continued on through what is known as The New Tendencies movement of the 1970s in Yugoslavia. For more on the New Tendencies movement and EXAT-51, see WHW, ‘Cornerstone Under the Grass: Innovation in Croatian Art in the 1970s,’ in: The Exhibitionist, No. 3, January, 2011, p. 5-8; and ‘Mission Impossible V: Revisiting Modernism,’ in David Maljkovic, Retired Compositions, published on the occasion of the exhibition Retired Compositions at Metro Pictures Gallery, 2009, (Galerija Nova Newspapers, No. 17), p. 3-5.

- Giorgio Agamben, ‘Notes on Gesture’, in: Infancy and History: The Destruction of Experience (London/New York: Verso Press, 1993) p. 137.

THIS ARTICLE HAS BEEN PUBLISHED IN METROPOLIS M No 5-2012. BUY IT HERE

Fionn Meade

is an independent curator and writer