Bad Painting gone Wrong

There is so much right painting right now, that it seems necessary to begin to consider its potential opposite.

Bad painting. It would seem to have reached its logical conclusion. Indeed, as we edge into the middle of the second decade of the 21st century, it becomes clear that the tradition of bad-painting has all but coagulated into a commodifiable type, replete with a mappable genealogy and codified discourse, and has, as such, forfeited its cherished brinkmanship to vex and offend. The duly belligerent, ill-mannered off-spring of the neo-avant-garde, the negative-neo-avant garde of bad painting seems to have done its due diligence in debunking myths of the (male) artist, authenticity, aura, and spirituality, through hyperbole, exacerbation and antagonistic opposition.

Thus did Christopher Wool’s recent Guggenheim retrospective strike an almost elegiac note, symptomatic less of a vital opening and perpetuation than a valedictory dirge and closure, while that direct scion of the mother (Kippenberger) of all bad painting, Krebber has all but become an identifiable and transmittable methodology, which Merlin Carpenter’s now iconic Die Collector Scum ironically formalized into a self-aware, ostensibly exsanguinated trope. This is not to say that this isn’t great work, but rather that the negative-neo-avant garde and the oppositional logic that once fueled it no longer seems to have the same purchase it once did for a reason as simple and preordained as: no more opposition. Besides, when did bad painting get so good? Those Josh Smith palm tree/sunset paintings, for all their hypertrophied irony, are categorically beautiful.

All that said, I am wondering if things haven’t gotten at once lot more banal and (thankfully) a lot stranger than “bad painting”, and if it might be more productive to consider them along the axis of a different binary (or if we shouldn’t jettison the logic of the binary altogether?): which is to say, not bad or good, but rather right and wrong. Indeed, there is so much right painting right now, by which I mean studied, correct, well-mannered, appropriate, downright derivative, and therefore egregiously academic abstraction (it seems if not pointless, then the petty stuff of schadenfreude to name already much-maligned names, but for the sake of argument, those current darlings of the market and whipping boys of obstreperous, soi-disant serious-minded criticism include: Oscar Murillo, Parker Ito, Lucien Smith, and Jakob Kassey), that it seems necessary to begin to consider its potential opposite. Which would be? Well, if we were to follow through on the logic of the binary, it would probably be figurative painting, but I don’t think it’s that simple (although figurative painting is currently, it must be admitted, pretty wrong). I think some serious(ly) wrong painting might be found between the poles of two artists as different as the Belgian, Brussels-based Walter Swennen (b. 1946) and the Canadian, London-based painter Allison Katz (b. 1980). Swennen because, unlike the right painters who seem to be born, fully formed with immediately identifiable, signature styles, under which they churn out a no less identifiable product, he seems to re-invent himself essentially from scratch with a slap-stick Beckettian moue of desolation with the production of each new painting, whereas Katz seems determined to not only cheerfully violate bans on craft and figuration but to also engage the nature and history of painting from a variety of unorthodox angles, which includes sculpture and digital print making. In-between the two of these artists, I think a handful of heteroclite practitioners of the medium stridently in the spirit of wrong might be– to proceed in very broad strokes– the American, LA-based Laura Owens, the Iranian-born, LA-based Tala Madani, German, Berlin-based Amelie von Wulffen and even the Swiss, Zurich-based Vittorio Brodmann.

Perhaps there is no better place to consider this alleged wrongness than by remarking two very obvious points about “bad painting” and “right” or “correct painting.” In some ways, they themselves could actually be seen to complement each other in a binary in so far as bad painting was supposedly, notoriously antagonistic toward the market, while right painting, it would seem, fully and unreservedly embraces it. Contrary to both positions, wrong painting seems to display not so much an indifference to the mechanisms and machinations of the market, but more of a genuine interest in experimentation regarding the limits, possibilities, and nature of painting, regardless of the market. In other words, it is not predicated upon rejection– unless it be the rejection of some (obscure) taboo– or reckless espousal (for lack of a better word); eschewing the apparent vanity of its counterparts, it says neither No nor Yes, but something altogether ambiguous, more open, and even ludic. Despite its obvious playfulness, humor and in some cases, ostensible perversion (Madani), such a proposition, at least in the hands of the painters I’m discussing here, comes from and seeks to remain within a very sophisticated discourse about painting.

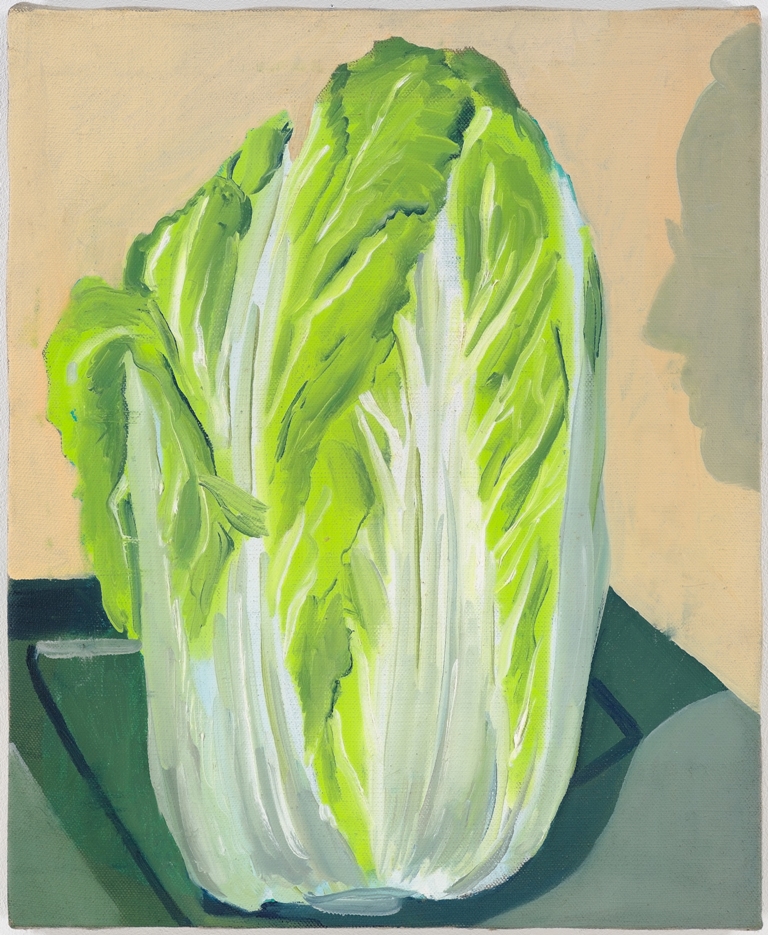

This inquisitive mode tends to manifest, more often than not, idiosyncratically, in that the logic of certain decisions might not be immediately within reach, never mind the logic of subject matter. Take for instance Allison Katz’s series of colorful portraits of heads of lettuce with a profile lurking in the background, or Amelie von Wulffen’s anthropomorphic watercolors of orgiastically fornicating fruit, or Swennen’s crude depictions of everything from a banana peel, to a brick wall, to a stick figure in a sombrero, or Vittorio Brodmann’s cartoon-ish, standup-comedy inspired flops, or Laura’s Owens large-scale, over-the-top, photo-shop, seemingly recombinable Mr. Potato-head doodles, Tala Madani’s bearded, badly-limned defecators, so on and so forth. Generally speaking, there is the sense here that a fair amount of this subject matter, which, in some cases, is as classical as it is confounding (all those fruit and vegetables, for instance), is chosen as much for its unsuitability, wrong-headedness, and so-called inappropriateness as it is for perfectly personal, i.e., idiosyncratic reasons.

Incidentally, if ever the spirit of dada is present in wrong painting, it is not so much its destructive side as its productive side– which is another thing that might separate what I am trying to sketch out from the monumental precedent of Sigmar Polke. Walking through Polke’s MoMA retrospective in complete and utter awe at the vastness of his inventiveness and heterogeneity, I found myself consumed with a kind of hypothetical, vicarious anguish that I presumed every New York painter must be visited with upon seeing that show– the stark, incontrovertible realization that not only has it all been done before, but basically one dude did it. Indeed, for all his dazzling variety, there seemed to be a kind of radical negativity at the heart of Polke’s practice, which all but immediately shut down whatever possibility it opened up, linking what he did, incidentally, more to bad than wrong. Perhaps much more fertile ground, a kind of genealogical gold mine of wrong, both in general and more specific to the artist’s in this article, would include the likes of Francis Picabia, René Daniels, and even Philip Guston– wrong, all of them splendidly, inexhaustibly, irredeemably and idiosyncratically wrong in their singular, idiosyncratic modes of figuration– as are the paintings and drawings of Lee Lozano.

When all is said and done, another thing that distinguishes bad painting from wrong painting is the former’s death drive, which exists arguably in stark contrast to the latter’s will to preserve, uncover, and continually stake out new, if forbidden ground. Where bad painting might edge inexorably forward toward the edge of the cliff, wrong painting moves laterally; one pushes the envelop forward, the other sideways, even backwards. Indeed to the end-game checkmates of bad painting, wrong painting sees painting as anything but dead, renewing it with each step. It is for these reasons that I am tempted to write that “wrong is the new right,” but wrong, if it is truly wrong will never be right.

Chris Sharp is a writer and an independant curator living in Mexico-City. Together with Martin Soto Climent he is leading the independant art space Lulu

A Dutch translation of this text was published in Metropolis M No 4-2014 Regels & taboes

ALS JE WILT DAT WE DEZE ARTIKELEN BLIJVEN PUBLICEREN NEEM DAN EEN ABONNEMENT

Chris Sharp