Pattern Recognition Florian & Michael Quistrebert

This week they are showing their work at Art Basel Miami: Florian & Michael Quistrebert. Agnieszka Gratza on blurry patterns, dancing Dervishes and their relation with astrology and astrophysics.

‘Abstract painting, now some 75 years old,’ wrote Bridget Riley in 1983, ‘is still relatively in its infancy. If Mondrian was the Giotto of Abstract painting, the High Renaissance is still to come.’ Abstract painting is a vast country, one more often than not defined by what it is not: non-representational, non-figurative, non-objective. For

much of her long career, spanning five decades or so, Riley has been more narrowly associated with ‘op art’ (though she has always rejected the label ‘op artist’) and its own breed of patterned abstraction, designed to play havoc with visual perception.

Mondrian: Nature to Abstraction – the title of an exhibition the British artist co-curated at the Tate gallery in 1997 – reflects Riley’s own artistic trajectory. Prior to her radical break with representation in the 1960s, Riley herself briefly turned to landscape motifs in such paintings as the Blue landscape (1959-60) or Pink landscape (1960), bearing the influence of Seurat, another one of her mentors. For art historian Richard Shiff, who gave a preview tour of the retrospective Bridget Riley: The Stripe Paintings 1961-2014 at David Zwirner’s London gallery in June, Riley became an abstract artist because ‘it’s a way of intensifying the effect she’s really interested in without having to be concerned whether the colour is in someone’s skin or in the tree outside of the studio; if she wants to explore that optical effect and the experience of the eye, for her the best way to do it is to do it abstractly.’

Not unlike Riley, the brothers Florian and Michael Quistrebert, whose practice à deux is still relatively in its infancy, began by making figurative landscape paintings in the Hudson River School style, fresh out of art school (they completed their degree at the Beaux-Arts in Nantes, where they hail from, in 2005 and 2006 respectively), before turning to abstract art. Their choice of medium was a way of going against the grain, according to Michael: in the 1990s and the early 2000s, during their formative period, relational aesthetics held sway and painting, abstract or otherwise, far from enjoying a High Renaissance was deemed completely outmoded in France.

Their more recent experiments with complex overlapping patterns of lines radiating out from a centre in the 2013 Scratched paintings or the 2014 GOD series, using a range of flimsy, low-tech – what Michael calls ‘anti-Beaux Arts’ – materials and flaunting their imperfections, put the Quistreberts at the forefront of what curator Matthieu Poirier dubbed the ‘Post-Op’ trend in a group show tellingly titled Post-Op: Perceptual Gone Painterly. 1958-2014 that took over Galerie Perrotin this spring. Poirier considers ‘Post-Op’ – whose roots go as far back as the textured, monochrome paintings and poor materials deployed by the Zero Group artists in the late 1950s – as a reaction against the neutral geometry, regular unbroken patterns and smooth finish characteristic of many Op art works.

What Michael Quistrebert sees as lacking in Op art is a spiritual quality. As far as he is concerned his brother’s and his own work comes out of a different tradition, brought to light by Maurice Tuchman in his seminal 1986 exhibition The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (lacma). The show had, among other, the merit of being the first to present works by the Swedish mystic Hilma af Klint. The exhibition catalogue, Michael confides, is his bedtime book. It has essays on topics ranging from theosophy to synesthesia, from yoga to hermeticism and other occult doctrines, examining their influence on abstract painting and its key practitioners.

Where many of their peers find the term ‘spiritual’, in the words of San Francisco-born Tauba Auerbach, ‘not only unfashionable’ but also ‘contaminated with a host of unsavory associations’, the Quistrebert brothers positively embrace it.

Their early painterly output – much of it produced in the course of a residency at Triangle Studio in New York in 2009 (a period of intense experimentation and new departures that Michael characterizes as their ‘fetal stage’) – attests to an undisguised interest in occult symbolism and spirituality.

The somewhat crude Masonic imagery (the triangle, the eye) pervading the black on black painting series inspired by the Chrysler building or the cathedral on Broadway, and even the Ex futuro (2010) video included in the 2013 Dynamo exhibition, co-curated by Serge Lemoine and Poirier at the Grand Palais, was apparently a rite of passage, something the brothers skimmed over. ‘It helped us transition towards geometry, towards the kind of work that we are doing now,’ says Michael. In his eyes, geometric art has a direct impact on the spectator; one need not be highly cultured in order to appreciate it.

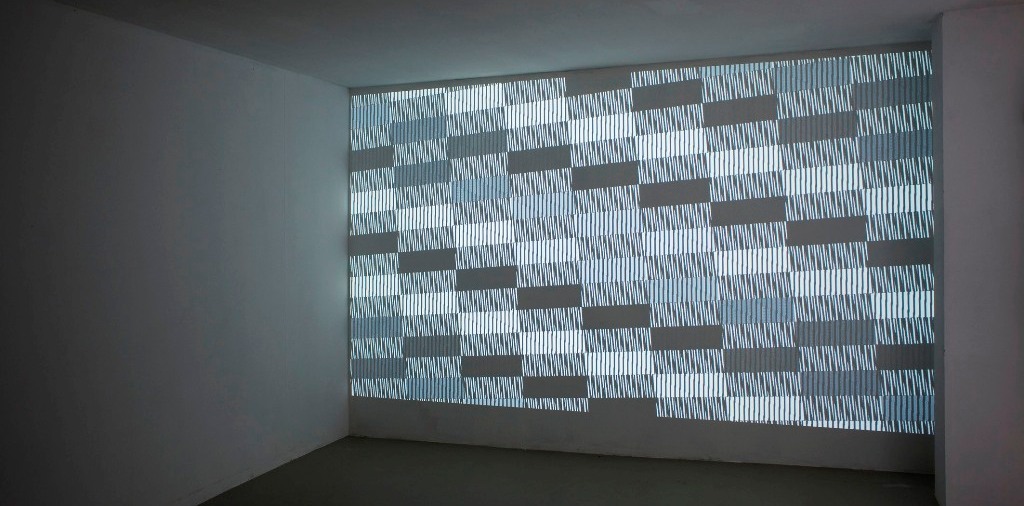

The Quistrebert brothers draw on a vocabulary of basic geometric forms – circles, squares, lozenges – that they invert, multiply, overlap to create complex mirroring effects and symmetrical patterns in their paintings and video works alike. Videos, sometimes shown on (paired) monitors, sometimes screened in a (ideally) dark room, and in the case of The Eighth Sphere (2010) in a room-corner, double-channel projection, are very effectively placed in dialogue with the painting series in their installations.

Titles like Ex futuro notwithstanding, these videos have a deliberately dated feel to them that keeps with the anachronistic analogue processing methods. Works such as the Circles, Squares, Lozenges triad of Amnesic CisenmA (2011), which riffs on Duchamp’s surrealist 1926 Anemic Cinema, featuring his whirling rotoreliefs, hark back to the experiments of visual sound cinema and the geometrical films of Norman McLaren, Oskar Fischinger or the Whitney Brothers whose influence the Quistreberts readily acknowledge.

Referencing most obviously John Whitney’s digital film Arabesque (1975) with its orientalizing decorative patterns and music – an early instance of computer graphics used to generate abstract geometric animations – the black-and-white HD video Dots was made for the 2012 Marrakesh Biennal, and drew inspiration from local motifs, rituals, and Sufi mysticism in particular. Conceived as an animated painting, and screened on a giant outdoor wall in Marrakesh, the video was made digitally but using filmed footage of a single Whirling Dervish, spinning round counter clock-wise, faster and faster. Shot from above, its white robes undulating around it, fluctuating in size from that of a rose petal to a stardust particle, the lone figure is multiplied and arranged into geometric patterns of growing complexity. At the cusp of figuration and abstraction, the resulting ballet of figures and formations is the Quistrebert brothers’ own attempt at creating visual music without sound.

Dots illustrates the Quistreberts’ penchant for the kind of analogical thinking that posits a relation between, say, the microcosm and the macrocosm. For the two brothers, the dervish’s dance is ‘closely connected to astrology and, to an extent, to astrophysics’ given that its core counter clock-wise movement mirrors that of the stars and of the universe at large around a centre point. A similar – albeit perhaps more rigorous and scientific – preoccupation with the interconnectedness of shapes and spaces also underlies Auerbach’s interest in the mathematical study of typology, which she sees as being ‘at the root of everything’.

This is reflected in the artist’s new body of work made for her recent solo exhibition at the ICA, which borrows its sub-title from Martin Gardner’s bestselling 1964 science book The New Ambidextrous Universe, concerned with the concepts of symmetry and asymmetry. The show’s eponymous centerpiece (The New Ambidextrous Universe I, 2013) was a floor-based plywood sculpture, whose thin waterjet-cut strips have been painstakingly reassembled in reverse order to form a rippling horizontal pattern that cuts across and visually disrupts the dark vertical wood marks. Disposed around it in the gallery space, on (mostly) white plinths of varying sizes, the immaculate 3D structures were made from glass and aluminium using the same water-jet technology. The twin interlocking powder-coated metallic tubes came in two contrasting colours, each a shadow or mirror reflection of the other, as if to suggest the existence of a parallel universe or anti-matter.

The same pattern and colour inversions are at work in the Quistreberts’ gesso painting on wooden panels from the 2012 White Gradient series, with their play of light and shadow, and from the black-and-white Mom and Dad gesso paintings, both from 2013. The dual and familial nature of their practice – the brothers professionally think of themselves as a ‘confraternity’ – is playfully reflected in the titles of the twin paintings Brother I and Brother II, and of their 2012 show at Galerie Crèvecoeur in Paris, Laure and Jane Dumond, which read out loud yields something resembling L’Origine du monde, the name of Gustave Courbet’s best-known painting. Florian and Michael, who divide their time between Amsterdam and Paris, where each has a studio and both have gallery representation (Galerie Crèvecoeur and Juliètte Jongma), consider that working together as a duo (something they did right from the start of their career) gives them a critical distance as well as a certain competitive edge.

Like Riley and Auerbach, the Quistreberts share with other non-figurative painters working today ‘a real belief in the metaphysical properties of work, materials, process and practice, a kind of secular faith in the possibilities of non-objective image-making’, as Christopher Bedford puts it in the introduction to his Dear Painter… article. Michael Quistrebert finds the perfect finish of Auerbach’s work daunting in its sheer flawlessness, which appears computer-generated even if it is handmade. Producing a perfect object is beyond his and his brother’s technological grasp, but then – he is quick to assure me – neither is it something they aspire to. Theirs is an art that wears its workmanship on its sleeve and bears its seams, the accidents of making, the ‘little irregularities’ which, according to Shiff, Riley refers to as ‘the sign of the hand’ and cherishes in her own work for all its surface regularity.

THIS ARTICLE WAS PUBLISHED IN A DUTCH TRANSLATION IN METROPOLIS M NO 5 2014 COMPLEXITY

Agnieszka Gratza