Democracy without the state Jonas Staal builds parliament in northern-Syria

Jonas Staal brings the New World Summit to Rojava to build a new parliament for the new Democratic Self-Administration in this region in northern-Syria, which was reclaimed by Kurdisch revolutionairies from the Assad-regime in 2011.

What is the idea behind this mission to Rojava?

The reason for being here is a collaboration with the Democratic Self-Administration of Rojava and the artistic and political organization New World Summit, that I founded in 2012. Together we are building a new public parliament in the Rojava region and organizing two international summits. It is through the New World Summit that the collaboration with the Democratic Self-Administration came about and that the members of my organization have been welcomed here three times since 2014. To give some context to this region: “Rojava” means “West” in Kurdish, and refers to the western part of Kurdistan – many people tend to refer to it as northern-Syria. The Syrian civil war in 2011 forced Assad to concentrate his army to the south of the country and left behind a power vacuum in the north. Kurdish revolutionaries took this momentum to reclaim their land and, in collaboration with peoples from the region such as Arabs and Assyrians, to declare their political autonomy in the form of “democratic confederalism.” This process is known today as the “Rojava Revolution.” In the democratic model that came as a result notions such as self-governance, gender equality and communalism take a central role. The revolutionary Abdullah Öcalan, who has been imprisoned by Turkey since 1999, describes this model as “democracy without the state.” Essentially: stateless democracy. The New World Summit consists of different people, such as researcher and producer Younes Bouadi, programmer Renée In der Maur, architect Paul Kuipers, photographer Ernie Buts and designer Remco van Bladel. Together, we have been developing for several years parliaments for stateless political organizations, amongst others in Berlin (2012) and Brussels (2014). These parliaments consist of large scale architectural constructions in which we so far were able to facilitate representatives of more than thirty stateless political organizations from all over the world, such as the Basque Country, Azawad, Somaliland, Baluchistan, West-Papua and Tamil Eelam. We believe the sphere of art is that of the imaginary, a space where we can develop new models of political representation and performative practices of politics. The Kurdish movement has been involved in this process since the very beginning: especially the women’s movement that inspired the philosophies of Öcalan and practices the ideals of stateless democracy to its outer consequences was very important in this process. Revolutionaries such as Sakine Cansiz, murder in Paris in 2013, rejected the idea of the nation-state as a patriarchal construct, inherently intertwined with the doctrine of global capitalism. With Öcalan, the women’s movement concluded that for a stateless people confronted with colonialism and occupation the nation-state can never be a solution, but forms the essential problem. The New World Summit always aimed to be a parliament for a stateless democracy, not limited to a specific territory, ethnicity or notion of statehood. This idea is indebted to the vision of the Kurdish movement, and our contributors Rojda Yildirim, Dilar Dirik, Adem Uzun, Havin Güne?er en Dil?ah Osman in specific. It is their political vision made possible a new artistic vision that we as the New World Summit try to realize through our parliaments.

Whose initiative is it to go to this region now, which in the Western view is so close to a war zone if it is not one?

During the first editions of the New World Summit we learned of the ideals of decentralized models of democratic self-governance in the history of the Kurdish movement. In first instance, this concerned Bakûr in specific, which is the northern-part of Kurdistan (Turkey) where different Kurdish communities already for some time have declared their local autonomy away from the repression of the current Erdogan regime. The Revolution of Rojava began to bring these ideals of democratic autonomy into practice for the first time on a large scale, the region covering about one and a half times the size of Belgium, with approximately four and a half million inhabitants. When we came here the first time in 2014 our intention was mainly to write about the revolution, to make a documentary and edit a book with texts from revolutionaries from the region, the latter of which was published under the title Stateless Democracy by our school, the New World Academy that is co-founded by BAK, basis voor actuele kunst. In Rojava we were asked about the work of the New World Summit by Amina Osse, co-Minister of Foreign Affair and representative of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and Sheruan Hassan, the Dutch representative of the party. The PYD stood at the forefront of the revolution in 2011. Osse and Hassan suggested the possibility to organize a summit in Rojava, to start building international exchanges between different international stateless political organizations and the Democratic Self-Administration of Rojava, but also to introduce academics, journalists, students and artists to the work that is being done here. Because Rojava is and wants to remains stateless, it made sense to think of a permanent parliament rather than a temporary one: a parliament for a stateless democracy. Since 2014 we began construction planning and programming, up until the day of today. Two days ago, we were able to have a delegation of twenty-five cross the border from Bakûr, South-Kurdistan (Iraq) to Rojava. The construction of the parliament has started, and this Friday and Saturday October 16-17 we’ll have the first of two international summits with speakers from the Democratic Self-Administration as well as other stateless political organizations from our network, such as Catalonia, Scotland, the Amazigh community and the Filipino revolutionary movement.

Could you tell us something about the design of the parliament and its location?

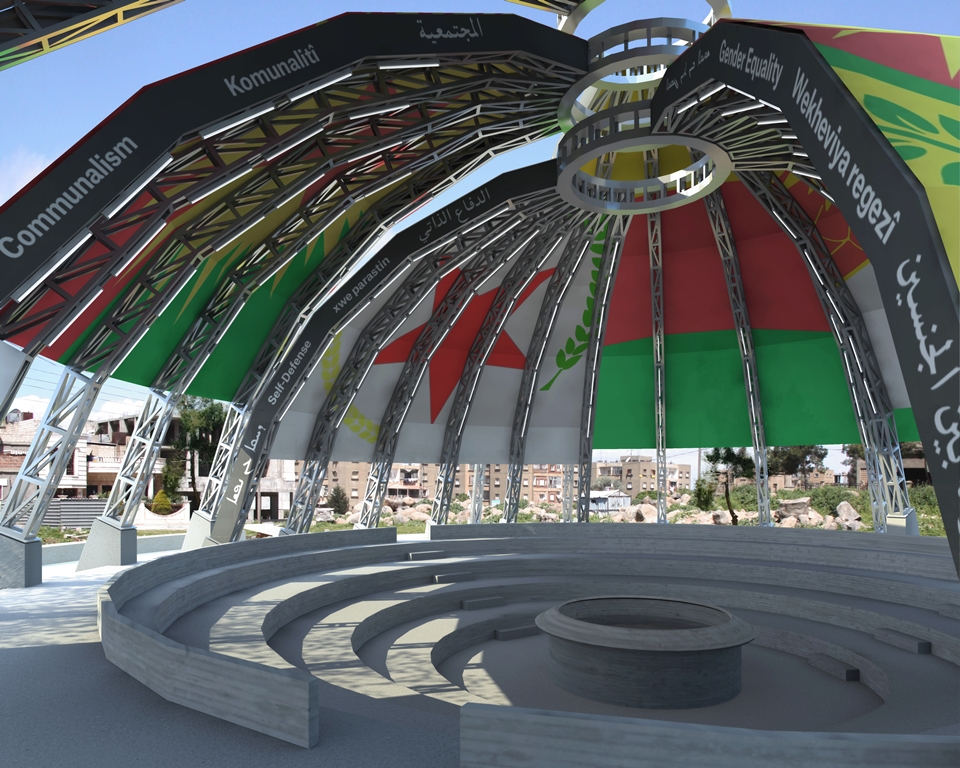

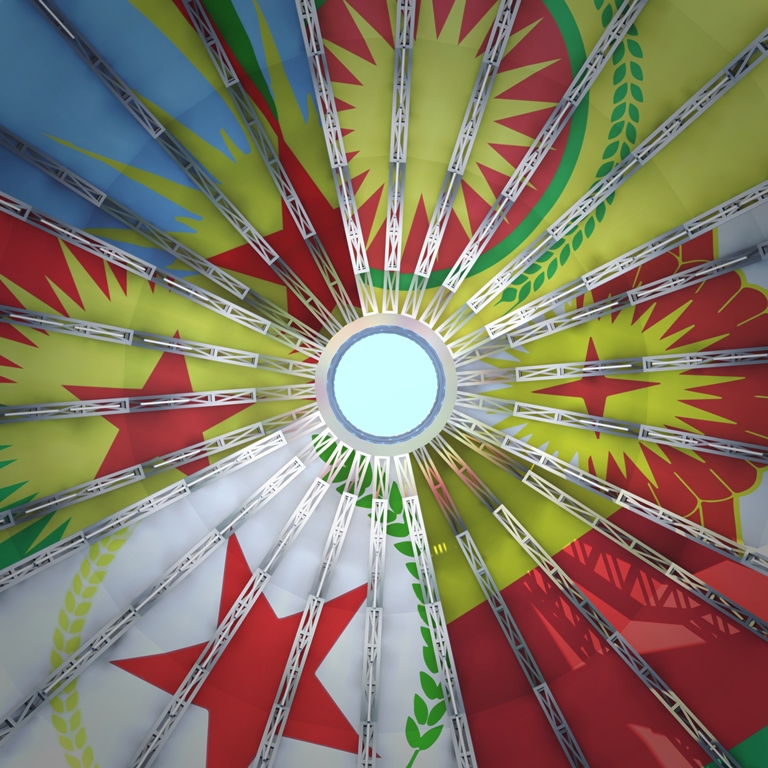

The concept for the parliament and the summit was developed by Amina Osse, Sheruan Hassan and our team. It is a construction in the shape of a sphere, with an agora – a kind of public atrium or theater – in the middle. This agora is a symbol of the importance that the Democratic Self-Administration places on local neighborhood councils, assemblies and city parliaments. Self-governance essentially means a politics constructed for and by the people. There is no or little difference between those who represent and those who are represented. Upon the agora of the parliament, a constructivist globe is placed, divided in six peals, each of which stands on pillars on which a specific word or concept is mentioned that is central to the Rojava Revolution, mainly taken from the “Social Contract,” which is the constitution of Rojava written by its different peoples. In Arab, Assyrian and Kurdish one can read “Democratic Confederalism,” “Gender Equality,” “Secularism,” “Self-Defense,” “Communalism” and “Social Ecology.” On top of the pillars, there are six large canvasses stretched over the parliament, each of which shows a fragment from a flag of one of the local organizations that plays a central role in the project of self-governance. Together, these fragments of flags constitute a new one: a prism of colors and symbols that form the ideological and political framework of the Democratic Self-Administration of Rojava. Around the parliament, we are developing a park, with works by artists from the movement, such as that of poet Kajal Ahmed and sculptor Abdullah Abdul. The location will be the center of Derîk, in Cezîre Canton, one of three cantons in total that make up Rojava. Two days ago, the name of the parliament was discussed in the local assembly, which will probably be “People’s Parliament.”

The New World Summit always aimed to be a parliament for a stateless democracy, not limited to a specific territory, ethnicity or notion of statehood

Was it difficult to produce?

Yes, for many different reasons. The scarcity of certain construction materials is one. The Rojava region is surrounded by the Islamic State, or “Daesh,” and has been able to defend itself effectively but at high costs. This war demands much of the resources from the region. Further, Rojava is not recognized by any state, even though the People’s Protection Units and the Women’s Defense Units (YPG/J) have been at the forefront of fighting a threat that has been created in part due to the devastating wars that the international community has waged in this region, the Iraq war in particular, with support of the Dutch state of which I am a citizen. There are also embargo’s on the economic exchange with Rojava, in and export, partly due to the pressure of the Erdogan regime and its fear that the Kurdish people – long suppressed in the history of Turkey – will undermine the regime’s wish for a one-party state. In part, solutions have been to work with as many local materials as possible and to find international support of cultural and diplomatic foundations willing to contribute to the construction of the parliament and summit, in which we succeeded. Most of all, limitations to any development or construction project is the ongoing criminalization of Kurdish revolutionary forces. In the case of the Erdogan regime, this took the form of starting a war over this summer against the Islamic State and the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). But only PKK suspects are arrested, as well as members of the democratically elected Democratic Peoples’ Party (HDP). Only a minority of the thousands of people arrested are supposed members of the Islamic State, which are treated with surprising respect, compared to the brutal way in which Bakûr, the Kurdish region, has been militarized by the Erdogan regime: the city of Cizîr only a few months ago was placed under siege by snipers, killing all that walked on the streets an cutting water and electricity; the body of actor Haci Lokman Birlik was dragged openly through the city of Sirnak by Turkish military; government officials blocked the help after an assault on peace protestors in Ankara that left a hundred people dead and two hundred wounded… In the meantime, the Erdogan regime bombs the PKK in Bakûr, while they are one of the few effective forces fighting the Islamic State. On top of that the PKK has announced several ceasefires and through Öcalan proposed a manifold of peace solutions, including the full acknowledgment of Turkey’s territorial integrity. The international community stands idle by its NATO partner. This shows the full failure and democratic deficit of our own states: their incapacity to support those who believe in democracy as something more than excuse to bomb the next country, but genuinely put the principles of people’s self-rule into practice. The obstructions for constructing a parliament are nothing compared to this campaign of criminalization for which the international community should be ashamed. We hope that the summit and international delegation that we’re organizing will help to deepen understanding of Kurdish culture and the Rojava revolution in particular. For our organization at least it is very clear that the only solution is the full international recognition of Rojava on its own terms, and not on the terms of the states that have caused havoc and disaster here in the first place.

Surrounded by an armed conflict, if not in the middle of it, you tend to think it might be a bit early for creating a parliamentary debate. It might even be dangerous. How is the local situation? Is the public ready for this kind of debate?

Democratic self-governance has been put to practice here since the very beginning of the revolution, no one waited a second. All local peoples have been involved, religious institutions recognized, the rights of women established through gender quota enforcing a minimum of 40% participation in political life and co-presidencies of one woman and one man for each political organization. There have been new universities founded, with an emphasis on women’s science, “Jineology,” which takes the colonization of women as a starting point to narrate alternative historiographies of minorities and stateless peoples. Neighborhood councils and assemblies were established, worker’s cooperatives organized, cultural centers build and the first film academy, the Rojava Film Commune, began its work only some months ago. The sacrifices are enormous, especially in the city of Kobanê that has been devastated by the attacks of the Islamic State and where many died defending the city. Every week there are ceremonies for martyrs, and there is hardly anyone that has not lost friends or family to the struggle. On top of that, in the middle of all these crises, many refugees are taken care of here. When studying the great accomplishments of this revolution, we cannot forget at the cost of how much loss and mourning that happened. Nonetheless, the Democratic Self-Administration time and time again emphasized that this is not a revolution of just weapons; it’s a revolution of “mentality” as they say here: a cultural revolution. Dilar Dirik once described autonomy as “living without approval,” with which she means to say that a revolution cannot outsource its results to a possibly better future: it must be realized in the here and now. Our autonomy is defined by how we act upon it. That is a lesson that stretches far beyond Rojava alone. In this region, that has been confronted with a history of colonization and imported foreign wars, a horizon has been created that concern all that believe in emancipatory politics. And all that believe in the importance of emancipatory culture. It comes at the cost of much, but for that there is a Kurdish saying: Berxwedan jiyane. Resistance is life.

New World Summit – Rojava, Part I

October 16-17 Derîk, Cezîre Canton, Rojava

Speakers: Quim Arrufat (Popular Unity Candidacy (CUP), Catalonia), Seham Dawood (Yekitîya Star, Canton Cizîre, Rojava), Sana Soleman Elmansouri (World Amazigh Congress, United Kingdom/Libya), Akram Mahshosh (Legislative Council, Canton Cizîre, Rojava), Katerin Mendez (Feminist Initiative (FI), Sweden), Amina Osse (Democratic Union Party (PYD), Rojava), Ziyad Rustum (Yazidi Free Democratic Movement, (TEVDA), Rojava), Ilena Saturay (National Democratic Movement of the Philippines Netherlands/Philippines), Hussein Shawish (People’s Protection Units (YPG), Rojava), Hadiya Yousef (Movement for a Democratic Society, TEV-DEM, Rojava)

New World Summit – Rojava, Part II

To be announced

Domeniek Ruyters

is hoofdredacteur van Metropolis M