Kevin Gallagher

Visceral Upcycling

The “circular economy” model imagines a new way of thinking about the flow of materials. It proposes a shift from the linear economy (take, make, waste) to an economy in which the constituent components of consumer goods are fed back into the fabrication of new products. What does its growing popularity mean for the arts?

I recently read that the Netherlands has made the “circular economy” the centerpiece of its program for the EU presidency this year. The aim is to turn the country into a “circular hotspot,” according to the official website of the European Commission.[1] The EU and the Netherlands are not the only ones pushing the agenda. In 2010, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation was founded to conduct research and raise awareness for this new type of economy. With the support of companies such as Cisco, Philips, Unilever, Google and Nike, the charity has more than six million euros to spend in order to achieve this goal. The circular economy promises to bring an answer to the question of what can be done once we have reached “peak stuff”, to use a term popularized by IKEA’s head of sustainability Steve Howard.[2] In other words: What is to be done when commodity markets are saturated and resources are depleted? In response, the “circular economy” model imagines a new way of thinking about the flow of materials. It proposes a shift from the linear economy (take, make, waste) to an economy in which the constituent components of consumer goods are fed back into the fabrication of new products. Recycling becomes upcycling in a re-branding exercise aimed at pointing to a shift in value creation: instead of simply re-using materials, surplus value can be generated through the management of resources. Goods become containers for materials that are recouped as assets once their product cycles come to an end, ready to be re-configured. The Dutch flooring company Desso, for example, has adopted a circular approach in which they offer to take back their carpets when customers are finished with them so that the materials used in their manufacture can be re-used. Once the product cycle of a carpet has ended its yarn and backing are separated, the yarn is re-used to produce new carpets and the bitumen backing is sold as a raw material to the road and roofing industries. All non-recycable elements are sold as fuel to the cement industry for additional profit.[3]

Materials thus only temporarily consolidate in objects that are always ready to be dismantled and disintegrated once their use value has expired. Accordingly, the future status of consumer products is one of constant transition, as materials re-configure and re-assemble. Part and parcel of this approach is the temporary ownership of these products. Philips didn’t provide the lamps for the new terminal buildings of Schiphol airport as such, but rather it provided the resource of “light.” Philips no longer sells a product that will eventually need to be replaced (due to a built-in duration) but instead manages a service. The company is providing the airport with light and the infrastructure that supports it for a specific amount of time. In accordance with the principles of the circular economy, once the service is no longer used, or the lamps stop functioning, Philips will dismantle them and take them apart in order to fix them or re-use their components.[4] Goods are increasingly rented, lent and leased in this way rather than owned, as their assets, the materials that they contain, need to stay in the hands of the companies that produce them. As such, materials (rather than objects) will become constants, as their formats perpetually change under the pressure for constant movement that capitalism seems to enforce.

The visuals that are produced to promote the circular economy are clean infographics and photomontages. They feature circular arrows, water and plants, and depictions of Earth being held in the cusp of disembodied hands. These images seem to say: we only need to control these materials and no waste will be created, no water will be polluted, only the most pristine chlorophyll will be produced. Just like Post-Internet in its worst forms, it’s a world of shiny, clean surfaces with few traces of humans – a self-sustained, polished, disembodied capitalist future that runs on its own.

Focusing on the circular economy’s novel approach to treat materials in particular, this text considers contemporary artistic practices that engage in forms of re-use: materials find second lives and are re-routed. In contrast to the state of affairs in a circular economy, however, these artworks and installations make apparent the infrastructures that are needed to maintain and support them. They present themselves as assemblages of materials whose destinies are as yet unknown, and they function as propositions for assimilation and disintegration. They are practices which go beyond the circular economy’s understanding of materiality by introducing chance, movement, interdependence, emotional attachment, waste and dirt to the slick concept of upcycling. What these works have in common with the circular economy however, is an understanding of materiality as process. Materials and objects here are no longer perceived as fixed entities. Digitization introduced us to an enhanced fluidity between formats. An image can become a video, be used as a backdrop of a Facebook profile, be modulated in Photoshop and then re-used, ad infinitum. We have become accustomed to the fact that content constantly morphs and adapts and now there is an increasing sense that this mutability might also infect the material reality we live in. Artworks are consequently no longer perceived as fixed entities but as part of material flows, just as consumer goods are within the circular economy.

Rebecca Stephany

Endless Re-Use/Confusing Assets

In order for the circular economy to work, the components of a product need to be able to be extracted in a re-usable condition, which is to say that they can only change in the controlled way that the circular economy has foreseen for them. Rebecca Stephany’s and Martijn Hendrik’s practices both engage in endless forms of re-use that complicate the distinction between form and content – or to use the lingo of the circular economy: good and material / shell and asset – as they constantly influence each other.

For the past two years, Rebecca Stephany has been working on Working Title, Working Clothes. The project started with her interest in the current labor conditions of cultural workers. While “digital spam”, as Stephany calls it, seeped in and mixed itself with the theoretical texts she was reading on the topic, Stephany registered her thoughts in a PowerPoint presentation that she made accessible online. The project then materialized in a collection of twelve shirts, each featuring the elements of her distilled research in a different way creating a kind of dysfunctional uniform that comments on as well as performs aspects of the cultural class’ current working situation. Since producing the shirts in 2015, Stephany has continuously re-worked the clothing line – sampling her own work, exposing it to different material processes, and reconfiguring it to the point that the shirts almost become an afterthought, as it most recently happened as part of a performance for (sic) hobbyists at STUDIO 47 in Amsterdam in June. The shirts were worn by the bodies of her friends and documented in a series of photos, exhibited on dilapidated racks and given artificial bodies of silicone inflatables before Stephany stacked all of their designs to produce one core pattern containing all of the individual elements. Stephany printed this onto a new shirt and used it as the starting point for a series of sculptures reminiscent of drawings she had made earlier in the process. She then equipped these sculptures with the ability to move, lending them wheels, crutches and other devices so that they could perform. Stephany’s work series has thus continuously evolved as she has re-used elements of previous iterations for the production of new objects. Stephany sees herself as a facilitator of accidents within this process, responding to the performances and outpourings of her materials as they continuously metabolize. There is no endpoint, no fixed “work.” Moreover, display and artwork, support and content are in a constant state of confusion. It’s never quite clear where to locate “the work” if the structures, objects and people that carry the shirts are mere helpers, props or facilitators or should rather be seen as integral to the sculptures, performances and happenings they are part of.

An artist who has worked in a very similar fashion is Martijn Hendriks who sees his works as open processes, porous formats. For the Amsterdam based artist, each mediated instance of a work (be it an image posted on Facebook or be it that an installation in an exhibition space) holds the potential to alter the work. As such, the context in which the work is placed, the infrastructures it engages with, constantly influences the work, creating a kind of feedback loop with the context the work is shown in.

Everything is Connected/How can we Upcycle if Materials Leek?

While Rebecca Stephany’s practice takes on the form of a metabolism in which she continuously re-uses, re-routes and re-purposes her own work Juliette Bonneviot’s work series Xenoestrogens registers the movement and ubiquity of a specific material – the female hormone estrogen as it occurs in the world around us. Re-use here takes place at the micro level of chemical compounds. Implicitly her works seems to ask: How can we upcylce if materials leek? Xenoestrogens consists of paintings and sculptural objects made from materials that contain estrogen: pigments, lacquers and silicone as well as pharmaceuticals, fungi and seeds. Seemingly inert, these material aggregations complicate a too-easy distinction between the dead and the alive. They show that material flows, the matter that our objects and bodies are made of, are a shared concern of the organic and inorganic worlds and depend on one another. Industrially fabricated hormones have become ubiquitous. They are not only effective in our bodies but fabricated as part of silicones, lacquers, oils, pesticides, detergents, plasticizers, linens, lotions, shampoos, beverage cans, contraceptive pills. The frequent use in recent years of the last of these in particular, and the ensuing increased concentration of estrogens in rivers, streams and drinking water supplies, has led to a decline in fish populations (as male fish have been feminized and their fertility declined), to mention one of the more obvious examples of such interdependence. Xenoestrogens makes apparent that the substances we surround ourselves with and the bodies we inhabit make use of the same chemicals – they depend upon and influence each other in ways that often can neither be controlled nor predicted. Just like with Hendriks and Stephany materials nest themselves in their contexts in ways that cannot be predicted hence complicating the highly controlled material world view that the circular economy promotes.

The Body Enters the Scene: Re-use as Ingestion, Matter Becoming Visceral

A heightened interest in materiality is also reflected in philosophical projects such as Speculative Realism and Object Oriented Ontology, which have fallen on fertile ground in the field of visual art in recent years. Materials have been labeled anonymous[5] and objects have been attributed lives of their own – lines of thought which have inspired countless articles and exhibitions, as well as most recently an entire issue of October Magazine.[6] The practices I am describing here share an interest in materials as active agents. Within these practices, however, materials are perceived neither as anonymous nor as having arisen out of nothing. They are man-made, and as such bring certain properties and histories with them – the baggage of meaning and memories.

As such, familiar household materials are re-used and re-considered in both Nancy Lupo’s and Kevin Gallagher’s works. In contrast to the state of affairs in a circular economy, however, it becomes apparent that the things and materials used as part of their installations are intimately intertwined with us, they are part of our memories and bodies.

Nancy Lupo

Lupo uses familiar objects, specific yet ubiquitous items taken from the everyday reality she experienced while growing up in the US: bathroom and dish racks, Rubbermaid brute containers and dollies; things that are mass-produced to be used in schools, restaurants and hospitals. In her most recent installation, Parrots and Parenting at the Swiss Institute in New York, fresh fruit is displayed on racks. It’s there to be taken; the fruit skins on the floor suggest that it has been consumed before and the paper rolls hanging on each side of the display seem to have been put there so you can clean your hands. Shiny red cherries were similarly presented in a bright red container as part of another of her installations at 1875 gallery in Oslo earlier this year. These installations are in a state of flux, inviting interaction. Just as the racks and dollies are de-formed and re-shaped, having been variously lubed, coated and flamed by the artist, the installations also transform as parts of them are consumed, rot away or are substituted as the seasons change (for the installation at the Swiss Institute the artist instructed the gallery staff to substitute the melons in accordance with the season). The objects Lupo brings to the gallery space are accompanied by the experiences and memories that are attached to them. Visitors are often drawn to these things through the familiarity they invoke. Yet at the same time the strangeness of the display and the conflation of different objects and materials (such as the meal replacement Soylent on baby seats and kitty litter on bathroom racks) serve to question these very connotations. We are invited to consider the objects differently, more viscerally perhaps, within a rotting, changing scenario that is at once welcoming and foreign.

The Amsterdam-based American artist Kevin Gallagher also makes use of materials that perish. Yet, whereas in Lupo’s work it is the life cycles of such perishable goods that are made apparent, and the ways in which they meet and dissociate themselves from our experience that are questioned, Gallagher is more interested in the level of care that goes into the upkeep of these materials. For his most recent installation at the Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam, the conditions required for the upkeep of gelatin are part of the experience of the visitors: Gallagher cooled down part of the space in order to preserve the gelatin he uses in his sculptures. The installation is divided over two floors, and occupies both the space that is kept cool by an air conditioner, and a second space that is heated by the exhaust from the same unit. Like in Lupo’s installations, materiality here becomes visceral as its effects are felt bodily. Gallagher’s sculptures and the material properties thereof are, he says, “sensitive, similar to our bodies, and hence create a kind of sympathy or alignment.”

Obsolescence and decay are entirely absent in the crystal blue and lushly green worlds that the circular economy promotes. In staging such processes, relating them to our bodies and memories, and in making the requirements explicit for things to function and materials to behave, Lupo and Gallagher’s works bring these notions back. They could be seen as memento mori; as the extended, fleshly and visceral counterpart to the flat, abstract and clean stock images of the circular economy, seemingly saying: don’t forget our bodies!

The interest in materiality here is not to be confused with a nostalgia for “things” in the face of an increasingly dematerialized and etherealized consumerism, as Graham Barnett recently (and quite convincingly) framed New Materialism, or “Etsy kissed by philosophy”, as he calls it.[7] It’s more than that. It’s about movement, flow, flux. By an approach similar to the Fluxus movement’s insistence on the materiality, waste and debris of objects at a time when the smooth surfaces and perfect forms of Minimalism and Pop Art dominated,[8] these contemporary practices question the ways we live with and engage with materials, often in a bodily sense, at a time that has recently been dominated by the sleek, image-focused works of Post-Internet. If Speculative Realism “requires the presence of no one”,[9] these practices all require and register presence; they invoke interactivity and invite us to think about our relationship with the materials and things used and the changes we and they undergo in the process. If we are on the threshold of engaging with materials and goods in a novel way and are to shift to more fluid forms of possession this will require new levels of control. If goods become services, the product will have to be constantly monitored so that the customer’s use can be registered (this is also why the circular economy is closely linked to the developments around the Internet of Things). In addition, the data generated to this end will most likely serve a secondary purpose as a saleable asset in its own right, an additional by-product. The artistic practices that I discussed, however, introduce more layered, complicated and personal forms of engaging with objects and materials in re-use. They remind us that materials change according to the context they appear in, that they often cannot be controlled and have the potential to leak. In addition, they point to the fact that we form affective, visceral bonds with the things that surround us that are hard to fit in the concept of liquid, clean and “possessionless” consumption. Finally, they highlight objects and materials as precarious, instable and perishable.

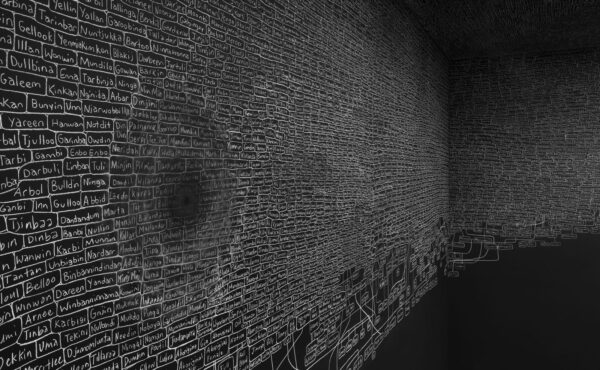

Kevin Gallagher

THIS TEXT WAS PUBLISHED IN A DUTCH TRANSLATION IN METROPOLIS M No 4-2016 SHARING

Melanie Bühler is guest-editor of ‘Sharing’ and a writer and curator, currently living in New York

[1] http://ec.europa.eu/environment/ecoap/about-eco-innovation/policies-matters/netherlands/netherlands-pulls-ahead-in-circular-economy-race_en

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/jan/18/weve-hit-peak-home-furnishings-says-ikea-boss-consumerism

[3] http://www.desso.co.uk/c2c-corporate-responsibility/cradle-to-cradle/

[4] http://www.philips.com/a-w/about/news/archive/standard/news/press/2015/20150416-Philips-provides-Light-as-a-Service-to-Schiphol-Airport.html

[5] On of the most prominent exhibitions organized that connected very explicitly to the ideas of Speculative Realism/Object Oriented Ontology was Susanne Pfeffer’s „Speculations on Anonymous Materials“ at Fridericianum in Kassel in 2014.

[6] A Questionnaire on Materialism, October 1955, Winter 2016, p. 3-110.

[7] D. Graham Burnett, in: A Questionnaire on Materialism, October 1955, Winter 2016, p. 19.

[8] Naitlee Harren, Fluxus and the Transitional Commodity, Art Journal, 75:1, p.44-49.

[9] Gregor Quack in A Questionnaire on Materialism, October 1955, Winter 2016, p. 81.

Melanie Bühler

is conservator hedendaagse kunst, Frans Hals Museum Haarlem