Roman Himey-Yarema Malashchuk, ‘Dedicated To The Youth Of The World I’, 2017, video, 2’, photo: Andrej Vasilenko

A sense of direction in The Maze and the Lighthouse – an introduction to the 14th Baltic Triennial in Vilnius

It is the question every biennial curator has to answer first: what, today, is still the necessity of organising biennials and triennials? Presenting a three-day film and performance program, curators Valentinas Klimašauskas and João Laia announce their intentions for the 14th edition of the Baltic Triennial taking place next year.

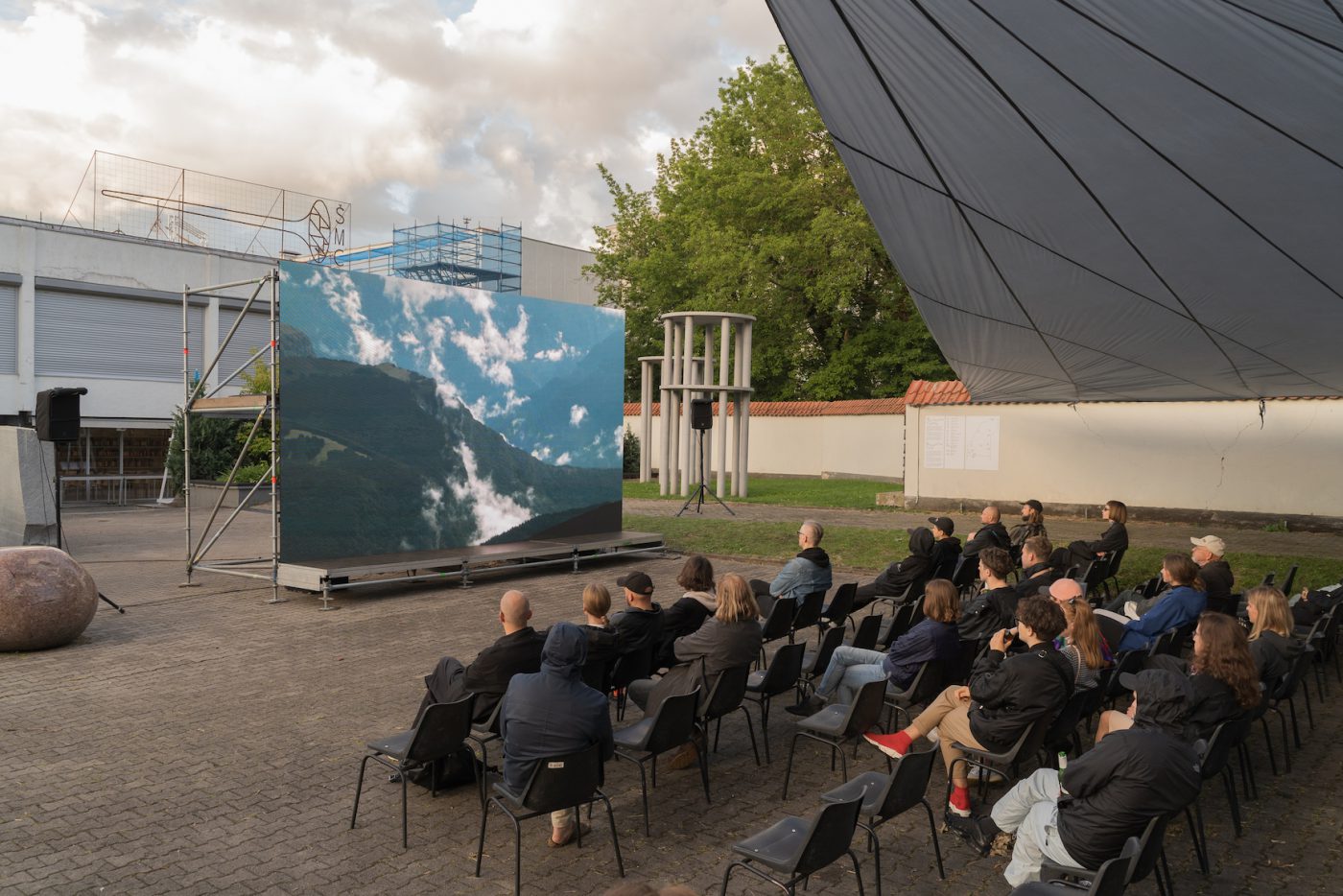

On a stormy evening in July I found myself in the centre of Vilnius at a parking lot-turned-sculpture garden adjoining the Contemporary Art Centre Vilnius, staring up at a LED screen. Its brightness made the sun shy away and its size humbled the tall sculpture by Antanas Gerlikas to its right and a permanent installation by Pakui Hardware to its left. Back in 2017 the decision had been made to turn this semi-private space back into the public one it was intended to be by the building’s architect Vytautas Čekanauskas, yet at present it sets the stage for an introduction by curators Valentinas Klimašauskas and João Laia about their plans for the 14th Baltic Triennial.

For those unfamiliar with it, the Baltic Triennial is a funny one of its kind. It’s both young and old. In 1979, eleven years before the fall of the Soviet Union, it was originally established as a periodic exhibition aimed at highlighting the work of young Baltic painters seeking exposure in a way that circumvented the strict hierarchy of the artists unions they didn’t belong to.[1] But it only truly came into its own after the fall of the USSR, when its direction was taken over by the then twenty-two year old Kęstutis Kuizinas — a curator who upon appointment immediately shifted its focus from modern to contemporary art.

Baltic Triennial 14: Intro Pavilion, concept and design by Ona Lozuraitytė & Petras Išora, photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Valentinas Klimašauskas and João Laia introducing the curatorial concept for the 14th edition of the Baltic Triennial through the film and performance program 'The Maze and the Lighthouse', photo: Andrej Vasilenko

When Kuizinas took his seat, the advent of biennials and triennials was near and dear. They popped up in every corner of the world, one that was becoming increasingly connected through open borders, a shared (English) language and the internet. The soft power tactics adopted by triennials and biennials to ‘modernise’ (read develop) a particular region are part of an old trick that can also be found in the disastrous effects of, for instance, the Olympic Games. Luckily, biennial gooroos and art-worshipers themselves have become more critical towards the format in recent years. We’ve become aware of the impact our presence has on a local community. We’re taking the train (sometimes the bus) instead of the jet, because we can no longer deny the damaging effects our ‘pilgrimages’ have on our environment. And in times of COVID-19, well, we don’t go at all and instead just flip open the laptop and join the guided tour or screening from afar. With all this in the back of our minds you do wonder: what, today, is still the necessity of organising and attending biennials and triennials?

Since Cool Places —the first edition of the Baltic Triennale in its new suit— opened in 1998, the event has steadily grown to become one of the most important exhibitions for the region, reaching far beyond the limits of Lithuania’s own borders and rich art scene.[2] What sets it apart from others of its type is the willingness of each invited curator to reinvent the concept of the format from scratch and in turn sidestepping widely accepted curatorial strategies. The 11th edition for example, which carried the title The Mindaugas Triennial, sought to channel the contributions of artists through one radically minimised vessel: a single human being. This explorative attitude has since pushed other triennials and biennials in the region to follow the Baltic Triennial’s lead. Further adding to the list of benefits is the fact that its existence instigated an influx of international artists and curators to Lithuania and, in return, brought Lithuanian artists to the international stage. The result? That you find yourself unquestioningly catching a flight to the Baltics and accepting the fated fourteen day local quarantine that awaits you upon arrival just to be there for the introduction and get a glimpse of what the next edition will bring.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, Valentinas Klimašauskas and João Laia, like their predecessors, avoided the stiff, archaic methodologies that normally make up introductions to triennials and biennials. Instead, housed under the title The Maze and the Lighthouse, a three-day film and performance program unfolded with work predominantly by artists who live and work somewhere in the former Eastern Bloc.

Curators Klimašauskas and Laia share concerns towards an expanding political division and the widespread surge of right-wing ideology in the Baltics and beyond

When I spoke to Klimašauskas about the objective behind this choice, he explained how it had grown out of a concern he and Laia share towards an expanding political division and the widespread surge of right-wing ideology in the Baltics and beyond. All the oppression and -isms that accompany these developments (such as climate change denialism, racism and sexism) made them curious to see how artists in other former USSR countries beyond just the Baltics are addressing this. This move of inclusion marks a first in the triennial’s short history. And so Klimašauskas and Laia plan to visit artists not only in Latvia and Estonia but also those living in Moldova, Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, Romania, and Hungary. Through the selection of films and performances that Klimašauskas and Laia presented during the introduction their personal curiosities to map such tendencies within the region became as clearly urgent as it is compelling. And even though the topics they addressed were anything but easy, the curators assembled a program that was hopeful, funny at times and, frankly, therapeutic.

Still from ACAB Mindstorm Online by Jaakko Pallasvuo and Viktor Timofeev, photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Uli Golub, 'Notes from underground', 2016, video, 13’23, photo: Andrej Vasilenko

For instance, in Notes from the Underground, a video work by the Ukrainianian artist Uli Golub (1990), we follow a fictional character through a rendering of the cramped spaces in his house. The walls are stacked with food, old newspapers are lined up against doors and windows, electricity flashes on and off irregularly and water drips from the ceiling. This work gives a glimpse into the daily life of a hermit who’s running away from a dystopian reality. The reasons for the onset of this situation are not made clear to the viewer, nor are they really important. All we need to know is that shit has hit the fan! When the character proclaims ‘And I sat there, watching, as it all happened live on TV’ I imagined the crowd sighing en masse. For who of us hasn’t stumbled upon a similar thought over the past months? Glued to our screens, quarantined in our own homes and unable to move, we watched, from afar, the swell of protest marches across the globe, the amount of COVID-19 related deaths and the easily forgotten irreversible rise of the oceans. Think again of this and all of a sudden the life of a fictional character becomes the healing channel through which we can face our own current trauma and distress.

A similar feeling was evoked in the ASMR-inducing video Hole by the Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo, who managed to find a metaphor for tunnel vision in the lure of his own broken sock. While the artist muses its beauty in the voiceover, shots of brown unraveling fabric slowly make way for a bombardment of images. Images ranging from stills of the nineties TV show Sliders to Caravaggio’s Doubting Thomas race pass as we follow from one gap to the next and meditate on our own fixation with views and standpoints. Yet just when you settle into the feeling, the video work ACAB Mindstorm Online that Pallasvuo made with Latvian artist Viktor Timofeev contrarily touches on what has become our new reality of working together apart. The work features the duo’s rendition of the process of making a collaborative drawing and ran back-to-back in between acts with Agnieszka Polska’s The Leisure Time of a Firearm —an eerie rendering of a giant eye infinitely staring straight into the barrel of a gun.

At the center of this three-day introduction —and the triennal that is still to come— is a tentative and optimistic question: And now...?

Sasha Litvintseva in collaboration with Beny Wagner, 'A Demonstration', 2020, video, 25, photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Poetry reading (in Lithuanian) by Tomas Venclova in the CAC Vilnius Library, photo: Andrej Vasilenko

Perhaps the highlight of the whole event for most was a reading by Tomas Venclova, a poet who only recently moved back to Vilnius after having lived in exile in New Haven where he, ironically, made his living by teaching Russian avant-garde cinema to students at Yale. His reading drew a large mixed crowd of both art lovers, historians and long lost friends. His presence felt like a reminder from the curators to their audience that the future is never as far away from the past as we perceive it to be. This was made even more clear when not even a week after the BT14 introduction took place, a rerun of Lithuania’s own recent past seemed to unfold in the neighbouring country of Belarus.

At the center of this three-day introduction —and the triennal that is still to come— is a tentative question: And now…? Yet its tone is not rhetorical or cynical, but optimistic. It’s aimed at helping us to tend to the sore parts of our current society. Both the choice of the medium for the event as well as its location support of this hypothesis as with both accessibility was key. This too served as a wink to what is still to come. Though the main exhibition of the upcoming triennal will still be held in the CAC’s majestic building, it will also spread out across Eastern Europe with iterations at several smaller events hosted in less politicised places. Perhaps the most eccentric on the list so far is Opium, Lithuania’s largest dance club. If the Baltic Triennial of 2021 is anything like its introduction, then we definitely won’t be bored by obvious themes, names or locations, but surprised and enriched by new ones. Another swell is growing. Come next May, join me on the dance floor.

[1]At the time, such fairs were not unusual in the USSR. Estonia, for instance, held a similar exhibition for graphic arts and Latvia dealt with sculpture. How much these initiatives and the choices for the disciplines came from each country independently is hard to say, as very little literature is available in English and, as a rule of thumb, the archives from before 1991 (when most Eastern European countries regained their independence) should be approached with some scepticism.

[2]In 2005 the 9th Baltic Triennial took place both in and around CAC, Vilnius, as well as in the form of a schizophrenic alter-ego titled The Baltic Triennial 33 ½, heldat the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London. In 2014 and 2015 the 12th edition featured exhibitions in Vilnius, Riga and Krakow. In 2018 the 13th edition took place in all three Baltic countries for the very first time.

Yana Foqué

is directeur van Kunstverein