Anna Dasović – Before the fall there was no fall. Episode 01: Raw material (2019)

On the representation of violence: in conversation with curator Natasha Marie Llorens

The current exhibition From what will we reassemble ourselves at Framer Framed centers on the representation of the genocide that occurred in Srebrenica and its surroundings in Bosnia and Herzegovina 25 years ago, but also focuses on the more structural question of the representation of graphic violence. We spoke with curator Natasha Marie Llorens.

Let us start by talking about how From what will we reassemble ourselves emerged. How did you come to take part in this exhibition, and how did you select the participating artists and researchers?

This is a complex project from a curatorial perspective. It began as a solo show, and it had a different curator: Katia Krupennikova. Anna Dasović took the decision to make it a group show before I was involved in the project. Dasović invited me because we share a lot of common ground on the question of violence, but also because she trusted me to argue with her and to understand the difference between an artist’s project and a group exhibition. I was asked to contextualize her work within a broader conversation about the representation of the genocide. Dasović had an exceptionally long list of people she wanted me to consider when I came into the project. Some had a personal and biographical relationship to the territories and to Bosnia and Herzegovina in particular. Some were dealing specifically with the genocide, and some of them were asking feminist questions about the representation of violence. From that list, I choose artists who had a clear and enduring relationship to the territories and who were focused on the more structural question of representation, rather than just the event of genocide in and around Srebrenica. In that sense, I built the project around Dasović’s body of work.

'I choose artists who had a clear and enduring relationship to the territories and who were focused on the more structural question of representation, rather than just the event of genocide in and around Srebrenica'

Marko Peljhan - Territory 1995(2009 - 2010)

Facing Srebrenica and the Future of Memory in Europe(2020)

Srebrenica is repeatedly discussed in the media. The controversial role of the Netherlands in Srebrenica and ongoing trials is covered in international media. How does the exhibition relate to these media representations?

My position as a curator and a thinker centers on representation in art, and this is a different conversation than one that foregrounds activism. We really need investigative journalism because of its commitment to certain journalistic neutrality, and we really need activism because of its commitment to a principled and articulated perspective on events like Srebrenica. Hopefully, this show is in dialogue with those practices, but it is not an attempt to tell people things they do not know. It is not an educational show. The exhibition is about like a deep structure, or about what conditions perceptibility. It deconstructs the images we accept unconsciously, such as some media representations of the Balkan subject. The work in this exhibition asks the viewer to consider the histories of representation that allow them to see certain people as civilized and certain people as uncivilized. I am interested in the construction of the frame rather than the event.

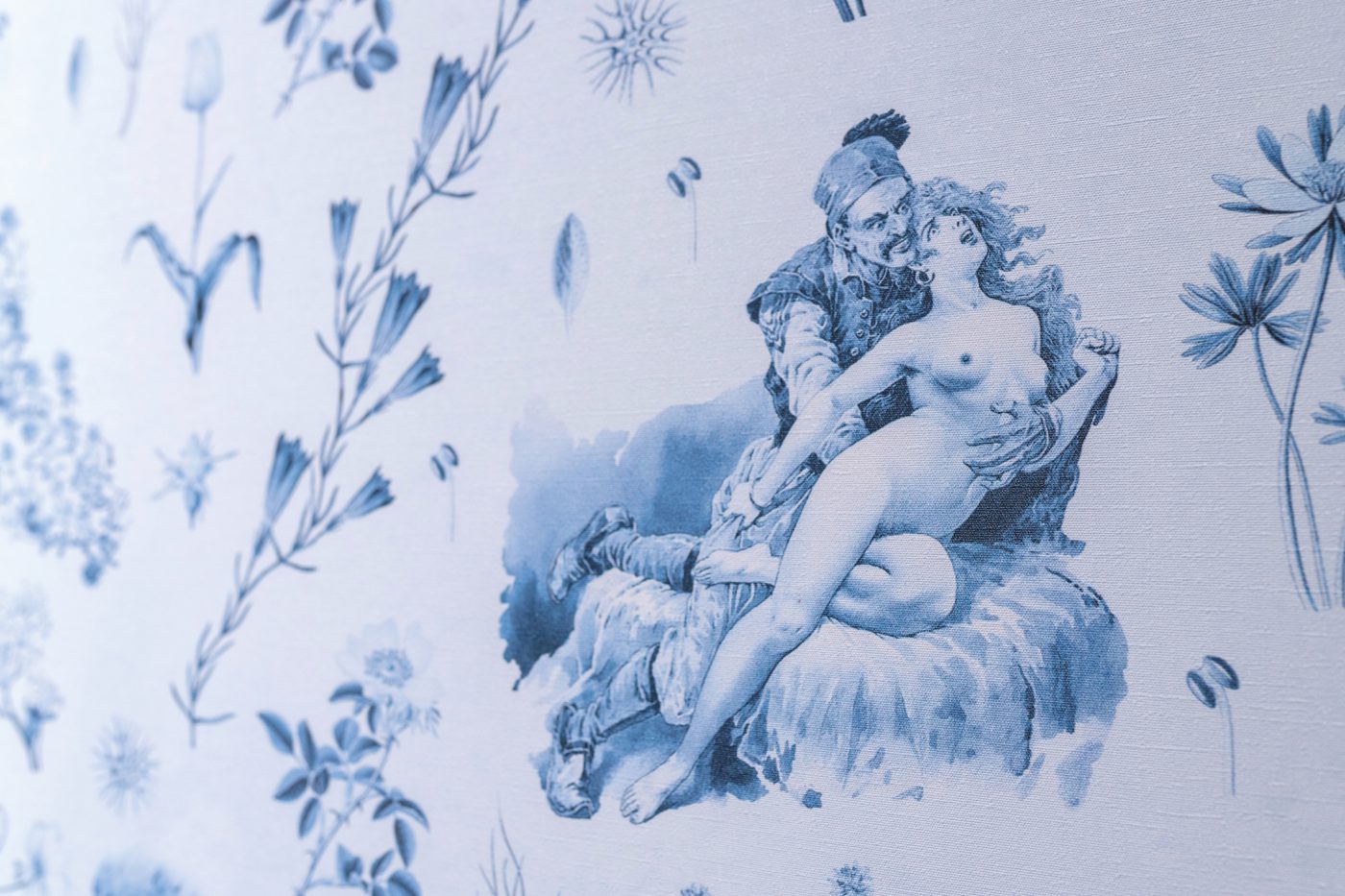

Lana Čmajčanin’s work, the Balkan Cruelty (2019), is a wallpaper drawing on 19th century imagery and it is a key work for me because it locates the beginning of racism against the Bosnian subject who is Muslim in the breakdown of the Austria-Hungarian Empire. Čmajčanin’s work is paired what Hito Steyerl’s Journal No 1 – An Artist’s Impression (2007) because Steyerl also traces a history of representation in the territories as just that—a history.

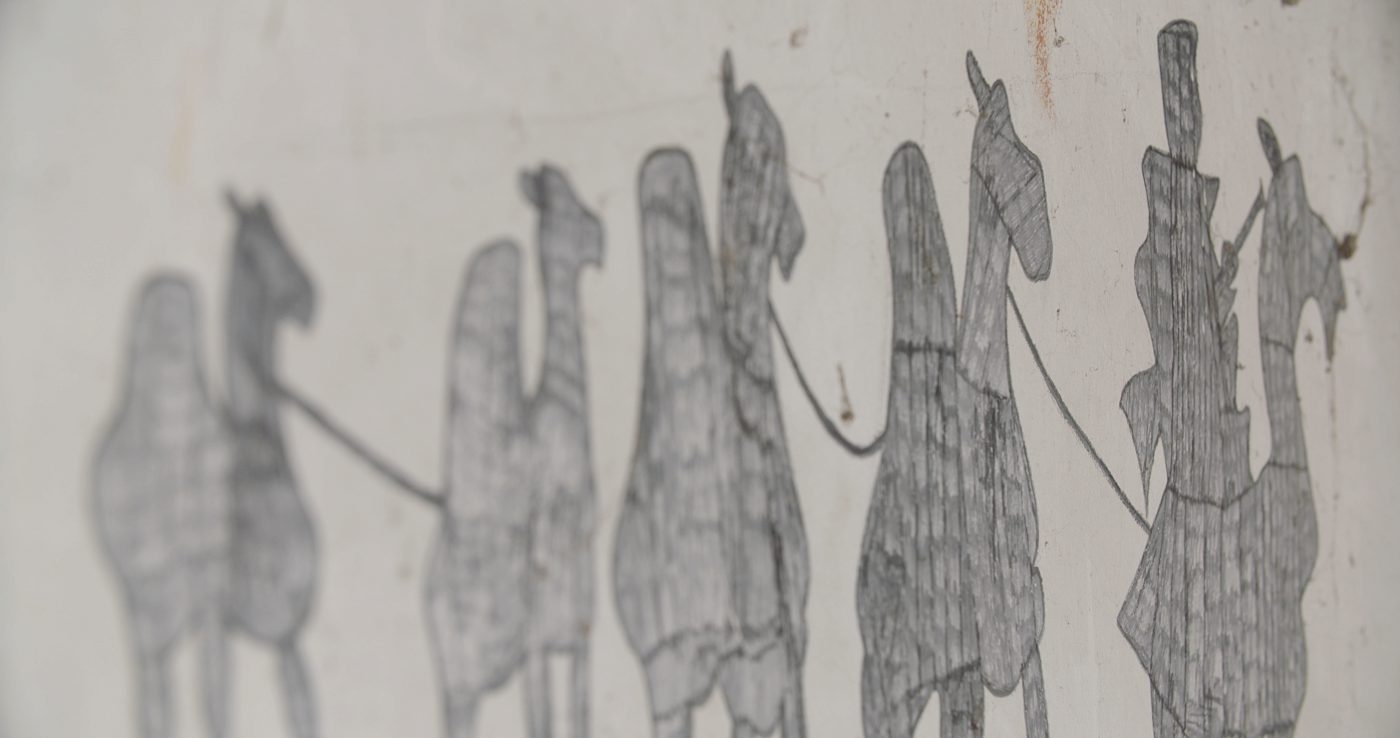

Dasović’s work is the most related to the media, activists, or politically engaged discourse because it literally shows that which remains, the visual traces of the Dutch presence in Srebrenica. But I think at the bottom of this work, or what really motivates her, is not showing evidence. This is my opinion. You should ask her, and she might disagree with me. I think what motivates her is tracing the ways in which whiteness tries to represent the world; the way whiteness claims this representational privilege as a given. Dasović renders how Bosnians who are Muslim are represented as a stereotype, or as a “Turk.” The drawings on the walls of the UN compound near Srebrenica do not picture the Turkish people, they represent Muslim identity as a stereotype. By panning over them slowly and pairing them with an account of their history—the history of Camel cigarettes and war—she deconstructs the Muslim subject reproduced by soldiers, tracks how its integration into a military imagination impact soldiers and their ability to protect the people they were sent to protect.

'I think what motivates Dasović is tracing the ways in which whiteness tries to represent the world; the way whiteness claims this representational privilege as a given'

Lana Čmajčanin - Balkangreuel – Balkan Cruelty (2019)

Lana Čmajčanin - Balkangreuel – Balkan Cruelty (2019)

Hito Steyerl -Journal No. 1 - An Artist's Impression (2007)

Anna Dasović - Before the fall, there was no fall. Episode 02: Surfaces

Representation of political subjects has always been a controversial issue in art. Especially after the Cold War, the identity construction of the Balkans became widely reflected on. What do you think about the representation of genocidal violence in current art practices?

It is tempting to fall into the trap of thinking ‘if we could just show genocidal violence and we could just see it, it would stop; we would stop it’. 1995 was an intense example of being aware of a genocidal event unfolding, or being able to see it. This does not have an automatic effect. There is an additional challenge with images of genocidal violence, which is that sometimes they can re-traumatize the viewer, impairing their capacity for empathy. We do not just need complex images of the genocidal violence because they are complex, we also need to learn how to look them. We need spaces in which we are confronted with them, time to find ways to be patient with them, so we can see the structures that justify that kind of violence with more subtlety and nuance. I see the role of contemporary art in light of this need for complexity and space to watch.

'Hoffner is thinking about how genocidal violence affects the body through the lens of queer theory. If we cannot take the body for granted as a stable identity, how can we do this necessary memory work?'

…what about the position of the artist in advancing the testimony through representation?

I take another example from the show to answer with: Ana Hoffner ex-Prvulovic’s Transferred Memories–Embodied Documents (2014).[1] Hoffner is thinking about how genocidal violence affects the body through the lens of queer theory. If we cannot take the body for granted as a stable identity, how can we do this necessary memory work? What is testimony without a stable “I”? I read Hoffner’s work as a response to this question, at least in part. To remember violence and to articulate this memory necessarily involves taking the event into the body and metabolizing it through some kind of relationality to another. We testify together, incompletely. We add layers of experience to the understanding of an event that is constructed collectively. Testimony cannot be produced alone, in other words, because that would rely on a fantasy of self-presence, which is just that—a fantasy.

'How do you make the public space admit those who have been excluded from it?'

Architectonical installation by Arna Mačkić for From what will we reassemble ourselves(2020)

Ana Hoffner ex-Prvulovic - Transferred Memories – Embodied Documents (2014)

Bosnian Girl Collective - Temporary Monument Srebrenica is Dutch History 2020

The exhibition is not limited to the works of the artists, but also includes research, interviews, and archival documents. In addition, it also questions the concept of a monument in the public sphere, by placing a temporary monument in front of the exhibition space. Could you tell me about the importance of this Temporary Monument – Srebrenica is a Dutch history by Bosnian Girl and how it contributed to the larger debate concerning public monuments?

Arna Mačkić, who is the exhibition designer and a part of the Bosnian Girl Collective, lobbied for the inclusion of a Temporary Monument in this project. Mačkić and Dasović really saw its potential contribution much more clearly than I did. It has been folded thoughtfully into the exhibition, but I do not think I can take credit for that. In general, though, I see the monument as a site for public memory. Monuments also close events that are painful for collective memory. Mačkić’s work goes against this traditional function, this closure, both in the Temporary Monument she contributed to as part of the Bosnian Girl Collective and as the exhibition designer who housed the exhibition in a monument.

How do you make the public space admit those who have been excluded from it? How do you create a site of the memory of an event that has been systematically repressed? Mačkić’s work responds to this question, I think. Her work goes against the notion of the classic monument, which is designed to celebrate victory, or achievement, typically through statues of men on horses and guns. The destruction of monuments in the context of the Black Lives Matter movement is a public rejection of the hierarchical, masculinist, and racist work that public monuments have done. I think Mačkić’s work hopes to trigger a different kind of memory.

From what will we reassemble ourselves, Framer Framed, Amsterdam, 6.9 t/m 3.1.2021

This exhibition project conceived by Anna Dasovic and curated by Natasha Marie Llorens. For more detail on the exhibition, see https://framerframed.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/FWWWRO_Handout_EN_Digi.pdf

[1] Ana Hoffner ex-Prvulovic is on the crossroads of who was born in 1980 in Paraćin (Yugoslavia), who was moved in 1989 and received capitalist citizenship (Austria) with a new name in 2002.

Nesli Gül Durukan

is an independent researcher, curator and art writer