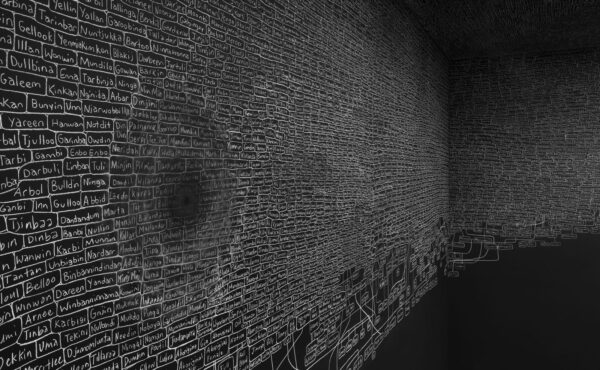

Jaws, Menstruation Myths, Laia Abril, 2018-2020, Courtesy Les Filles du Calvaire

“We are just starting to see the surface of the institutional problems”: an interview with artist Laia Abril

In her long-term visual research project, A History of Misogyny, artist Laia Abril names her chapters with straightforward titles. After Chapter One: On Abortion, she now exhibits Chapter Two: On Rape at FOAM. Jue Yang speaks to Abril about the problematic portrayals of violence and survivors in the media and the way Abril creates visual metaphors and connects difficult stories in her work — with ambitious and much needed perspectives in the era of #Metoo.

Abril was the recipient of the FOAM Paul Huf Award in 2020. In the current exhibition of Chapter Two: On Rape, she guides the viewer through challenging territories. Her texts synthesize real-life accounts and events with a documentary vigor, while her images mediate reality through visualizations and metaphors. The chapters — rather than describing “the act of rape or the act of abortion” — unpack the societal prejudices and institutional failings around these acts. “There have been euphemisms and ways of sugar-coating these topics,” she says, “the titles represent how uncomfortable and stigmatized these topics are.”

[h1]THE PORTRAYAL OF RAPE

In the introduction text to Chapter Two, you write: I wanted to understand why some institutional structures of justice, law and policy were not only failing survivors, but actually encouraging perpetrators through their preservation of particular power dynamics and social norms. I [identified] gender-based stereotypes and myths, global prejudices and misconceptions, that have prevailed and perpetuated the culture of rape. When you look at “the culture of rape” with a global scope, how and where do you start looking?

[answer Laia Abril] I wanted to tackle institutional rape, so I first looked at what contributed to it — the institutions of marriage, the church, the military… It was difficult to explore rape rationally — I had to do it more personally. As I looked at pieces of history, culture, trials and events, my choices started to depend on how the information affected me. Would this shock me? Would this help me connect things? Would this help explain why some laws are so draconian? I gained some peace as I started to understand the origin of the problem, a peace that I also want to offer to the audience.

What do you think of the current portrayal of rape in media?

[answer Laia Abril] Rape has appeared broadly on the covers of newspapers for the first time because of the #Metoo movement. Yet the attention on rape has focused again on the survivors who have to endure all the pressure. They have to defend themselves not only in courts, but also against the media and victim-blaming groups. When it comes to public discussions of rape, the survivors have been put in a position as “the face of the solution”. I wanted to focus more on the institutions and take the pressure off of the survivors.

'When it comes to public discussions of rape, the survivors have been put in a position as “the face of the solution”. I wanted to focus more on the institutions and take the pressure off of the survivors'

Installation overview of Laia Abril's 'On Rape: A History of Misogyny,Chapter Two' at Foam, photo: Christian van der Kooy

Installation overview of Laia Abril's 'On Rape: A History of Misogyny,Chapter Two' at Foam, photo: Christian van der Kooy

Installation overview of Laia Abril's 'On Rape: A History of Misogyny,Chapter Two' at Foam, photo: Christian van der Kooy

Your work carries a forensic aesthetics. The photos provoke the association of autopsy and the catalog of old medical museums. How much of this aesthetic choice is intentional?

[answer Laia Abril] In Chapter One: On Abortion, I made aesthetic choices with the intention to confuse and surprise people about the time period of the images. In Chapter Two, I addressed what I consider problematic in the way we have been photographing rape as a society. When you think of the classical photojournalistic images portraying survivors, these survivors are often portrayed from behind, looking out through a window. I believe this practice enhances re-victimization due a patronizing, colonialist and misogynist gaze. What you interpret as forensics aesthetics in my work is actually my personal reaction – I am trying to make some sense of the many emotions and thoughts, so that I become able to connect and display them.

Your texts, like your images, do not depict any graphic acts. You have decided against the use of such images for Chapter One: On Abortion. Are you making the same choice in your chapter on rape?

[answer Laia Abril] Rape was an invisible act until very recently. We had seen romanticised depictions of rape in fiction, but it was not until CCTV cameras and cell phones that we were able to see actual footage. How we represent violence affects the ways in which we view and judge the issue – I believe it is much more important to focus on how we got to this kind of representation and why we seem unable to alter it. Think of the video of the killing of George Floyd seen by millions. Yes, we acknowledge and discuss issues because of the video; but the footage plays at the emotional expense of his privacy, his family and his community. Online conversations from the African American communities have urged people to stop sharing that video; I find this discussion relevant as we talk about rape or any kind of visual representation of violence.

To depict violence directly is a second act of violence not only to the victim but also to the viewers of the images. In the current mediascape, we are constantly consuming and absorbing violence. We are shocked, worn out, and we get cynical about these images. This cynicism from unmediated portrayal of violence can lead to the dismissal and simplification of otherwise complex narratives.

[answer Laia Abril] There is also a second act of violence which are the trials, you see many examples in the exhibition on how the political and the judicial processes are. They are ridiculously violent towards the survivors, especially when the media is involved. These obstacles are the reasons that survivors have a difficult time to denounce their rapist. In the case of La Manada, the survivor was anonymous, yet groups from the US found out who she was and leaked her personal details and photo all over the internet.

When you think of the classical photojournalistic images portraying survivors, these survivors are often portrayed from behind, looking out through a window. I believe this practice enhances re-victimization due a patronizing, colonialist and misogynistic gaze

Laia Abril, Shrinky Recipe, 2019, On Rape C Courtesy Laia Abril & Galerie Les filles du calvaire

FAILING INSTITUTIONS

The first part in your current exhibition features photos of life-sized garments: dress, military uniform, prison uniform. Above each photo is a testimony with a name and a country, in which people recount the traumas they have experienced. You see this installation as “portraits of institutions”. In what sense?

[answer Laia Abril] The testimonies are not about the acts of rape themselves; instead they are testimonies of how the survivors were failed by the institutions, before and after rape. The images represent those institutions as well as the millions affected by them. This way of portraying the survivors and its perpetrators allowed me to expose the massive, systemic issue that rape is and has always been.

Among the garments, one is the religious habit of a nun. The perpetrator in that story is a “she.” It is an unexpected story and it shook me. As you identify stereotypes, do you seek out stories that defy these stereotypes in your work?

[answer Laia Abril] During my research, I realized my own idea of rape was outdated. I decided to add examples of female sex offenders, to highlight issue in the transgender community as well as to speak about the fact that men get also raped. Misogyny is not just hate against women, it t has a toll on men and people identifying with every gender. It stems from systemic violence. As a woman, I felt uncomfortable when I first thought about female sex offenders, but if I were to ask theaudience to reflect on uncomfortable issues, I should question my own comfort zone. I learned to put myself in complex situations.

In Chapter Two, you quote misogynist speech from US judges, congressmen and the 45th president. The rape kit in one installation is also from the US. The US is a conflicted place where misogynies thrive among #Metoo activists. Are these rhetorics and artifacts originated from the US representative of the global scope you are trying to cover?

The testimonies written above the garments are not about the acts of rape themselves; instead they are testimonies of how the survivors were failed by the institutions, before and after rape

Installation overview of Laia Abril's 'On Rape: A History of Misogyny,Chapter Two' at Foam, photo: Christian van der Kooy

Church Rape, On Rape, Laia Abril, 2020, Courtesy Les Filles du Calvaire

Laia Abril, Ala Kachuu, 2019, On Rape, Courtesy Laia Abril & Galerie Les filles du calvaire

[answer Laia Abril] This is one of the hardest parts of the project: to show many countries, movements, cultures under one umbrella. Every time I select a story or angle, I choose one that represents bigger ideas, one that helps me connect with more people. The US rape culture — through media, fiction, and the extension of the US culture in general — has influenced many countries, including my own. It is an important culture to reflect on.

What angles do you choose to connect with more people?

[answer Laia Abril] With the testimonies, I focus on the emotions after injustice: the frustration, anger and hopelessness. I believe these emotions are universal, though they are experienced by different individuals and under different situations. I am aware of my own biases: I am a white, middle-class, privileged cis-woman from southern Europe. I have my limits in putting myself entirely in the shoes of other people. Yet I do feel connected to their pain. I have to navigate the issues of representingthe pain of others. To what extent is it okay for me to talk about them? How can I help them to talk about themselves?

In your work you often place points next to their counterpoints. An example that comes to mind is the installation of the beating stick in Chapter Two. It is a weapon from the anti-rape gang in India. The women are taking matters to their own hands and making themselves heard. At the same time, they are employing violence.

[answer Laia Abril] The idea of justice it’s a complicated one. It differs from one culture to another. It means different things to each individual. Whenit comes to punishment, I decided to review the radical ways of punishment of sex offenders. I want to expose the absurdity of the institutional solutions. I will explore reparation more when I work on the book.

Your images and installations are re-enactment. Some of them are re-interpretations of reality. They are not necessarily documentary. They create visual associations.

[answer Laia Abril] The images in Chapter Two are more visual metaphors. These images are connected to reality — they are reactions to real events and facts. They are not evidential images in a way that we traditionally define documentary. At times I actually found myself pursuing a sort of visual poetry. As soon as you read what they are about, this association of beauty changes and you start to feel uncomfortable.

Jaws, Menstruation Myths, Laia Abril, 2018-2020, Courtesy Les Filles du Calvaire

Penis Truth, On Rape, Laia Abril, 2020, Courtesy Les Filles du Calvaire

MOMENTS OF TRANSFORMATION

I also see how the personal necessity you describe can be emotionally exhausting. How has the project affected you personally?

[answer Laia Abril] During the research I was overwhelmed by the statistics of rape. With On Abortionit was very clear for me to see how things could be fixed — logistically, bureaucratically or technologically — despite the obvious stigma. However, rape is a much more complex issue. I felt hopeless when I realized the extent of how the institutions were failing us and that I was not going to see its end in my lifetime – that had a clear impact on me in terms of the role and meaning of what can art do in this cases.

Your work creates an understanding and a platform on topics that many people find difficult to share. What are moments of transformation in your work — for yourself and for your audience?

[answer Laia Abril] When I was photographing the garments, I had received some of the dresses for the first time. We had been measuring them so that they were printed in real-life sizes. The dresses had lengths of 185cm, of 170cm, etc. When the dress of the little girl from Colombia arrived, it broke me into pieces. Her dress was only 30 centimeters. It was so small. That moment of photographing was a moment of alchemy. Another transformative moment is when people look at my work. That’s when I see the evidence of the impact. From the perspective of an artist, it’s emotional to see how people relate to my work, how they look at it and how they move in the room. I was at FOAM when I saw three women. They sat in the room for maybe half an hour, only looking at one story. I wondered if they might be from the country mentioned in that testimony. They were so moved by it thatI had to leave the room. I suddenly felt very connected to them.

Recently a case of rape allegations toward a Dutch artist, Julian Anderweg, came to light. It is similar to Harvey Weinstein — only that Anderweg is 30 years younger than Weinstein and it concerns the realm of fine art. It seems that #Metoo has reached a point where people feel able to step forward more than before.

[answer Laia Abril] I think we are just starting to see the surface of the institutional problems. That’s why institutional rape interests me in the first place. We still see the repeated shaming and blaming of victims. There are those who are doing the hard work to denounce the perpetrators, and there have been more trials and collective social pressure since #Metoo. But it’s still a draconian system. The sentences are often disappointing. The act of violence keeps happening. And sometimes it’s not yet safe for the survivors to come forward.

Laia Abril delves into complicated stories through both exhibition- and book-making. She is currently working on the publication of Chapter Two, in which she explores the nuances of complex subjects — such as the reparation of violence — that have emerged through the exhibition. She is also planning on the next chapter, On Mass Hysteria, and re-conceptualizing the topic of Menstruation Myth, which she has worked on previously. Her exhibition, A History of Misogyny, Chapter Two: On Rape, is exhibiting at FOAM until March 7, 2021.

On Thursday 10th of February, at 19:00 hrs CET, FOAM organizes a conversation between Laia Abril and Carmen Winant online.

Jue Yang

is a writer and filmmaker