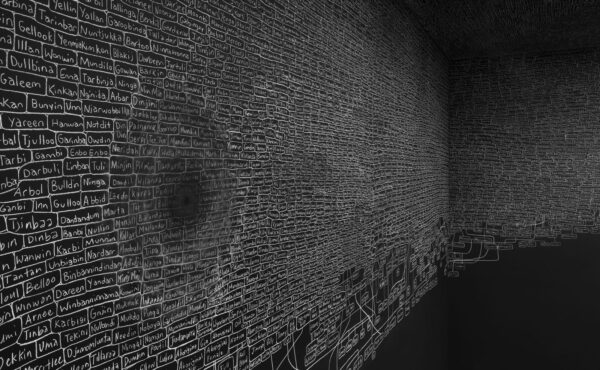

Sandra Mujinga ,’Midnight’, installatie Vleeshal Middelburg, 2020, fotograaf Gunnar Meier

Learning from Grief

After a year of loss, Staci Bu Shea refects on the meaning of grief. ‘Grief is here, irresolvable and unwavering, and that does not change.’ We must learn how to live with it. Art and literature can help. They are full of life while also carrying death, at the same time, in the same moment. (PODCAST: Staci reading her text – listen here)

“The only thing that is different from one time to another is what is seen and what is seen depends upon how everybody is doing everything.”

That’s the statement repeated three times by poet Gertrude Stein throughout “Composition as Explanation,” written and delivered as a lecture in 1925-26. She connects war’s influence on warfare, modernism on art, and her writing process as “groping toward a continuous present, a using everything a beginning again…” I have been thinking about this statement as an anecdote again and again in the varying facets of my daily life, like a prophetic guide for making sense of things. Yet the simultaneous vagueness and complexity of Stein’s formulation in a year like ours is unsettling and a subtle truth that’s somewhat hard to bear. We have change fatigue, and many of the answers we seek already exist and they must emerge newly in the present, but regardless we have to go search for them. I’m concerned with how everybody is doing everything because what’s being done is not seen by everybody and when it’s seen it doesn’t always matter to everybody. If we can agree that everything is constantly changing and social and political movement work is sustained and continued by the quality of its people power and imagination, we need to get clear on our long game principles for collectivity, a beginning again, but using everything that we know from those who came before us.

In the past year we have seen many acts of solidarity, both direct action and performative pledges, spurred by an insurgence of crises, through statements from arts institutions, open letters acquiring signatures of support, hiring announcements, and generally, cancelations and postponements. This is challenging and messy work, and there is immense loss and grief in the process. If only we who must do so could figure out how to do so. We need to find ways to be gentle with our spiral of thought, and to be able to work with it between urgency and endurance. There are a few questions that circle: Where do we each find ourselves within the simulation of Stein’s composing? Could I be the one that I keep talking about who can only truly transform through the relationships closest to them? How can we allow ourselves to be changed and transformed, let alone the structures and practices within the arts where we work? One way to bring about structural change is to create and implement new orthodoxies within institutions. And that is exactly the paradox: what do we do when we have worked toward systemic change, after years of struggle, and then we realize forces against us have bounced us back in time, beginning again?

Scholar Robert Pogue Harrison writes of a similar paradox in his thorough survey The Dominion of the Dead (2003) that “we dwell in space, to be sure, but we dwell first and foremost within the limits of our mortality. Those limits are not merely restrictive but are in fact generative of the boundaries–spatial and otherwise–of the worlds where history, in its temporal unfolding, takes place.” (19) This life force that restricts and generates is also responsible for legacies of violence. People in power fear mortality and create incredible suffering in very psychic and material ways. Would this insight be the solution? That dealing with the reality of our own death, and knowing that we all share that reality, makes us a little more attentive and kind? It could be said of all the basic phenomena known to us about human life and history: we should know by now yet we have a long way to go.

[blockquote]My proposal is to take the dynamics of grief very seriously to inform our shared principles

Sandra Mujinga, Seasonal Pulses, 2019, courtesy Croy Nielsen

Lately I am thinking from the perspectives of mortality and grief as a way to inspire and transform sense and life in the present. My proposal is to take the dynamics of grief very seriously to inform our shared principles. Grief is here, irresolvable and unwavering, and that does not change. Rituals and performative manifestations are ways of sharing grief in a depersonalized way, and that is something we can learn from. Art and literature help us to witness our and each other’s senses. They are full of life while also carrying death, at the same time, in the same moment: they are place-bound, and place is something mortal. The location-specific reality of art and literature puts us in the present, both when you create it and when you take it in. I have noticed lately that in the presence of death, of dying, and of the grieving process surrounding it, the senses are most alert, acutely aware of the environment and the hyper-reality it contains. I think we, if I can claim, are most full of life when we see the possibilities that our feelings and our senses hold. Art and literature help us share and deal with our mortality and grief.

Harrison continues, “for if poetry has the power to make the naught resound, if it has the power to house, bury, and commune with the dead, it is because it’s rhythms, accents, and elegiac tones have their elemental source in human grief. If the transmutation of the earth into invisibility is at bottom a poetic task, and if we have the ability to undertake such a task, it is because human beings are veterans of mourning.” (54) He writes about the history of ritualizing grief and how it makes tangible the crisis that lies within grief, precisely by objectifying its content through scripted gestures and precise codes of enactment. He introduces a vivid report by nineteenth-century ethnographer Bresciani in his study of Sardinian customs morte e pianto rituale (death and ritual crying) and witnessing these performances in action. Bresciani writes how the female performers quietly enter the room where the deceased lay, “faces restrained,” “as if they hadn’t happened to notice that a coffin and a corpse were there.” Then, registering what they see, the women let out painful shrieks and sobs, throw themselves to their knees or to the coffin, and thrash about while pulling out their hair, wide eyed and chattering their teeth. After the dust settles and the room falls to silence, they gather close together fixated on the coffin, and then “one of them, as if touched and lit by some sudden powerful spirit, jumps to her feet, shakes herself, becomes animated, reawakens, her face becomes flushed, her eyes sparkle and turn towards the deceased, she breaks into a song.” (58)

Grief ceremonies have their own set of norms, schedules, mimetic gestures that have been passed down through generations

Grief ceremonies have their own set of norms, schedules, mimetic gestures that have been passed down through generations. “Far from being a spontaneous or cathartic expression of grief, the ceremony enacts at the symbolic as well as psychic level the movement from “irrelative” grief (i.e., chaotic or unappropriated emotivity) to an objective or socially shared language of lament.” (58) Those involved externalize and depersonalize grief, which makes possible interpersonal participation in the lament, involving collectivity in recitals, planned exchanges, and collaborations that wouldn’t be possible in the individual regime of mourning. Rituals also have the power to slow down time and notice the present.

Dedicated and thorough research of the life’s work of our dead could be intentionally reframed and performed as a collective grief ritual. Especially for lives lived at the margins and taken by violence. Anchoring grief as a principle in our lives can help us imagine the new forms we long for. This is part of our work in the arts as well. Perhaps the statements of solidarity from art institutions, whether sincere or not, are a necessary performativity to bring about more structural change, a transformation, to match their written promise of accountability. Using everything, we begin again, and within the limits of our lives we wait for each other to arrive. Actual change comes mainly from collective effort. An endless, tiring effort that inevitably goes hand in hand with grief. Some things are certain: our grief is immeasurable and difficult to bear on our own, but as a collective we have the strength for it. Bernice Johnson Reagon, scholar, activist, and song leader, already shared an answer in her lecture and essay “Coalition Politics” from 1983: “Be sure you get on your agenda some old people… Think about yourself that way. What would you be like if you had white hair and had not given up your principles? It might be wise as you deal with coalition efforts to think about the possibilities of going for fifty years. It calls for some care.”

Thank you, Maartje Schulpen, for our invaluable conversations.

EEN NEDERLANDSE VERTALING VAN DEZE TEKST IS GEPUBLICEERD IN METROPOLIS M NUMMER 6 2020/2021 STRATEGIEËN VOOR DE LANGE TERMIJN. STEUN METROPOLIS M, NEEM EEN ABONNEMENT. ALS JE NU EEN ABONNEMENT AFSLUIT STUREN WE JE HET NIEUWSTE NUMMER GRATIS OP. MAIL JE NAAM EN ADRES NAAR [email protected]

Revised in English since the original print publication in December 2020

Stein, Gertrude. Composition as Explanation. London: Hogarth Press, 1926.

Harrison, Robert Pogue. Dominion of the Dead. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Johnson Reagon, Bernice. “Coalition Politics: Turning the Century*.” Essay. In Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology, edited by Barbara Smith. New York: Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1983.

Staci Bu Shea

is curator at Casco Art Institute: Working for the Commons