Sanne Kabalt, a doorway, entrance or gate, photographic prints on duraclear, 2022, solo at Razklon Gallery, Bulgaria

‘Leaving room for silence and hesitation’ – in conversation with artist Sanne Kabalt

Surrounded by darkness in the Finnish woods, Sanne Kabalt started singing. It made her feel comfortable out there, all alone with her camera. Ever since, singing has been a prominent part of her artistic practice. ‘These works feel closer to me than everything I did before.’

You often describe your work as ‘site-specific’. Could you elaborate on that?

‘One thing that I have always found intriguing is the fact that while you and I are currently in one place, the rest of the world continues to exist. Right now, while you are sitting at your desk at home, there is a cloud enveloping a mountaintop. And the other day, when you were caught in the wetness of the cloud on the mountain, your desk and chair were still here, patiently waiting for you. This amazes me. By merging images – mostly projected or translucent ones – I try to evoke this sense that there is more than one thing, more than one place.’

Did your Bachelor studies in photography (2007-2011) inspire this interest?

‘It did. And so did my master’s. For my MA thesis at the DAI (2016-2018) I wrote about the verb “capturing,” which is generally used to describe what photography does. By capturing something we imprison it in a rectangular shape. This very defined format makes me shiver. Things are too complex to be captured within it. When photographing a landscape, you cut off whole parts of it, depending on where your image ends. You are cutting trees…! When photographing people, this practice of capturing becomes even more complex. During a residency at Het Vijfde Seizoen (2016) I worked with psychiatric patients, initiating conversations between them. Though I wanted my work to speak about mental health, I was worried about how my portraits of the interviewed patients would be interpreted. Would people think I “captured” the insanity of these people? I would never pretend to know what that looks like or suggest that a specific person embodies it.’

Can you give another example of a work in which writing and photography meet?

Sanne Kabalt, father, sleeper, circulating photograph, unfixed in its frame & 7 texts, 2007

‘For father, sleeper (2007 | 2018), I wrote down thoughts that arose while looking at one particular photograph that I took eleven years prior, resulting in a series of short essays. Each essay started with the phrase “I took a photograph of my father sleeping on the couch”, and continues to consider questions such as: is it fair to capture somebody while they are sleeping? What is the relation between sleep and death? Can we hold a person in a photograph? And can we wake him? This way of writing, of mixing philosophical questions with personal memories, brought the image to life for me.’

‘Is it fair to capture somebody while they are sleeping? What is the relation between sleep and death? Can we hold a person in a photograph? And can we wake him?’

Portret Sanne Kabalt, 2023. Photographer: Wouter le Duc

Sanne Kabalt, Zolang je niet zo over problemen praat zie je er toch niks van, photographs, crayon drawings on photographs & text [book], 2016-2018, in the solo-exhibition ‘I see you are not there' at Beautiful Distress House, Amsterdam

While you were talking about it, the photograph just moved in its frame. Is that on purpose?

‘The photo is only loosely fixed to the frame. When you hold it, it moves around. I really like how this makes the image feel “alive”. When I show this photograph in exhibitions I ask a few people to take care of it and hand it to others. That way, it really is in the visitors’ hands, and after holding it for a while they are free to pass it on or to leave it against the wall, next to another artwork, on a table, and so on. It makes the viewer relate very differently to the image than if it was hanging in a fixed place on the wall. Combined with the short essays that are exhibited in the same space, it’s an intimate and often unsettling experience.‘

Are these kinds of interactions and movements through the space a returning strategy in your work? At your most recent exhibition to lull and by(e) at SYB you also performed while holding a projector, moving its light along the walls like a searchlight.

‘Yes, I think that movement is a way of blurring boundaries, of making things more than only one thing. During the residency, I regularly sang my 5-months-old daughter, who was with me, to sleep while walking through the space. In Dutch we have a word for it: “ijsberen”. Many parents, like polar bears in a zoo, go all the way to the end of our houses and back. Motion reminds the child of being in the womb and makes them feel safe. This, in combination with the singing voice, lulls them to sleep. The image that the projector threw on the wall were the shadows that my daughter and I cast while I sang her to sleep. I extended this process during my lecture-performance by switching between speaking and singing lullabies while walking through the space with the projector.’

Did having a child change your artistic practice?

Sanne Kabalt, to lull and by[e], installation/lecture-performance with moving projections of photography and video & voice, 2022, presentation at Kunsthuis SYB, Beetsterzwaag

‘Yes, it changed everything, as I guess it does for most people. I now need to be available for my daughter; while that can be practically limiting, parenthood mostly had positive effects on me and my artistic practice. Generally, I feel more calm and content, because of the deep love I feel for her. I was very happy to have the residency at SYB scheduled relatively soon after giving birth, because I experienced that I can be an artist and mother at the same time. Experiencing that really helped. Plenty of people go on thinking that a mother cannot be a serious artist, which made me quite anxious in the beginning. But I too am more than just one thing. I believe that with more life experience we become richer beings and therefore better artists.’

‘Plenty of people go on thinking that a mother cannot be a serious artist. But I believe that with more life experience we become richer beings and therefore better artists’

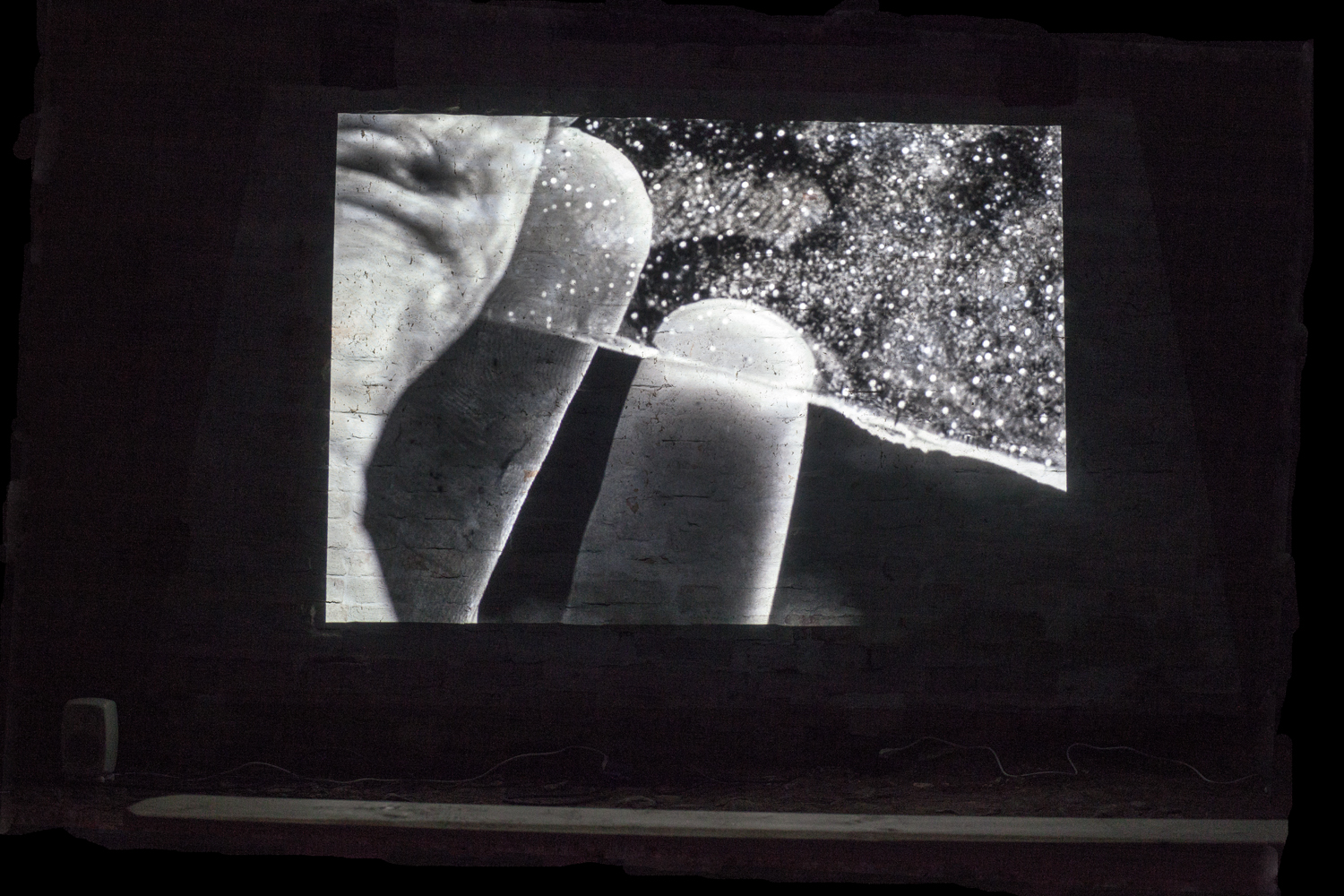

Sanne Kabalt, 1.4, video, voice, projection, 2019, exhibited at Saari Residence, Finland

Let’s move a bit back in time: the lullaby project is not the first time you used singing as an element in your work. When and how did you first integrate it into a work?

‘It was during my time at DAI. We had to do many performative things there, which I was not used to, coming from photography. When I had to give a presentation about my thesis, I decided to not only speak, but also sing, and to my surprise, it worked. Singing became another way to unsettle the idea of photography as “capturing”. Shortly after graduating from DAI, I went to the Saari residency in Finland. I was outdoors a lot, but it was winter, so I would be surrounded by darkness. Singing helped me feel comfortable out there, alone with my camera. It was so empty and quiet; there was no one around that could be bothered by my singing. In the end, my voice became the main element of the video work 1.4 I made there. I wanted to blur the distinctions between the process of making the work and the piece itself. In the video, you sometimes see an image or a scribbled text, but mostly you just hear my voice speaking and singing in a dark space. The title, “1.4”, refers to the aperture I shot the photos with, one that is used in the dark because it lets in as much light as possible. While making the work, I remember wondering whether I was “allowed” to do this. Looking back, that’s a strange question when it comes to art. Everything should be possible, and in the end, this work felt closer to me than everything I did before.’

What does it mean to you to sing?

‘When you start to sing, emotions immediately pop up. Singing does something to your memory, it makes you think of people you heard singing in intimate settings, perhaps. It adds a completely different layer to my works. For example, in shiver (inside), the site-specific installation I made during the Destination Unknown residency (2021), I combined my singing with a spoken poem and filmed footage. I enjoy using singing in a low-key way, without instruments and without singing complete songs, leaving room for silence and hesitation.’

Do you write your own songs for these works?

‘I have written some songs of my own and I have also tried using them, but it does not work yet. It feels a bit forced for now. Also, I like using a familiar song and stripping it down, so that people can still recognise the melody. For shiver (inside), I used a John Lennon song. People respond differently to words and melodies they recognise, even if only vaguely. For the lullaby piece that I am currently working on, I have been gathering many lyrics, cutting and pasting them into new songs, drawing attention to the recurring themes and struggles that are voiced in these songs. I sing fragments of the lullabies in their original language. To me, it’s not about the beauty of singing; I really like the practical function of these lullabies; they have the power of summoning sleep. They are sung one-on-one, and usually at home. I am interested in this very intimate act of singing.’

What fascinates you about the content of the lullabies?

Sanne Kabalt, shiver (inside), video, projection, poem, voice, 2021, at ‘Destination Unknown’, Tegelen

‘Lullabies are so beautiful to me, because they often express the struggles of mothers or other carers. They tell about poverty, loneliness, fatigue, loss… They offer a place to voice these struggles while, paradoxically, soothing the child. After so many sleepless nights, you do get exhausted. You could simply say that you are exhausted, but you could also describe it as a dragon that just wants to bite the baby if it is not going to sleep. Many lullabies feature monsters or “fabeldieren” (imaginary creatures). My own short stories also situate themselves somewhere in-between reality and dreams. I am inspired by the dreams and nightmares that I have been having since I was a young child. It is a gift to be able to remember those intense images and feelings when I wake up; I could not just make them up during the day behind my laptop.’

‘I worked a lot around mourning and loss in relation to people and now I want to investigate it in relation to landscape and cold. What about the loss of winter?’

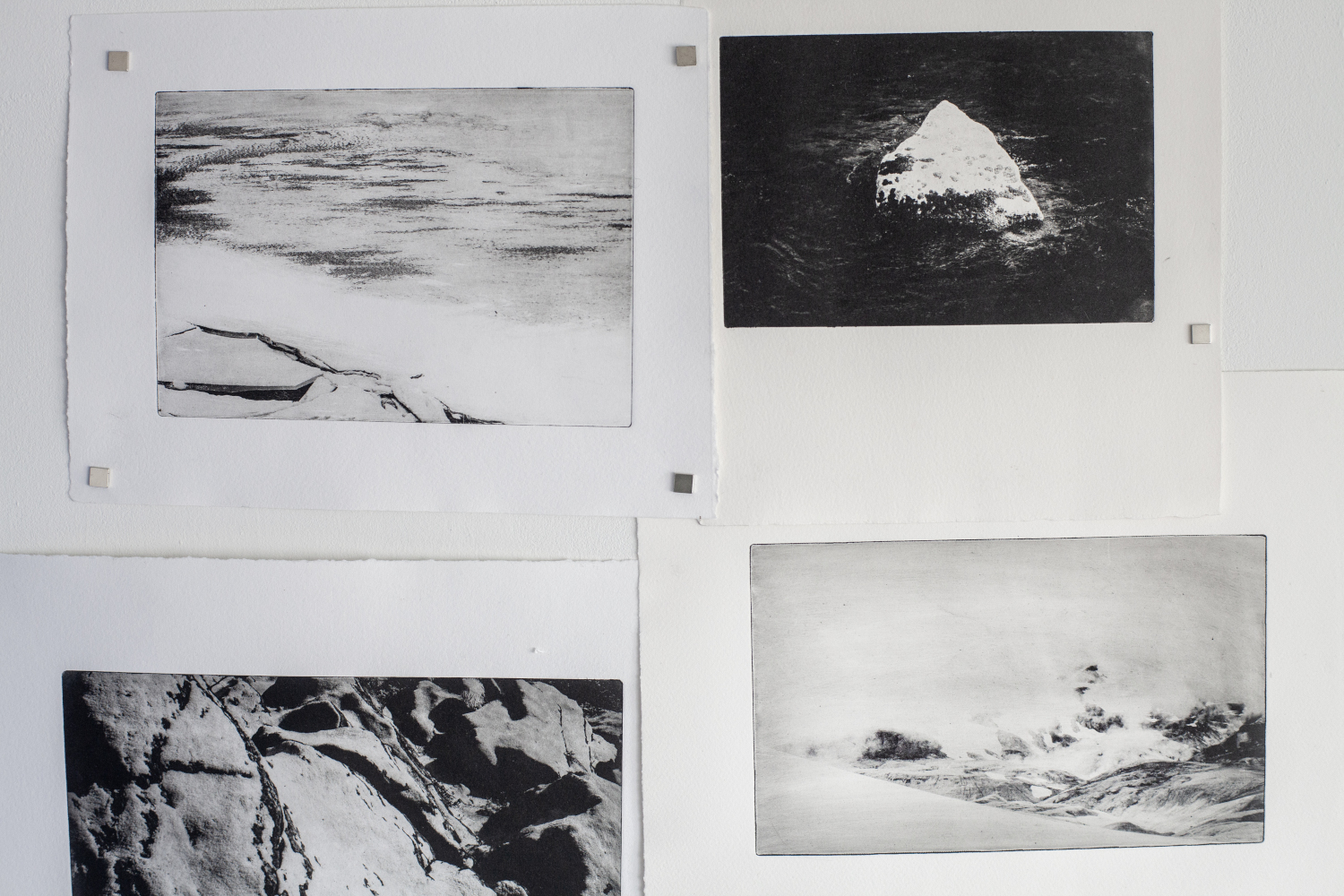

Sanne Kabalt, untitled/work-in-progress, 2023, photopolymer prints on studio wall

Do you often draw from personal experience?

‘My works are indeed inspired by things I have experienced. I have made works about losing my father at a young age, for example. My grief, and my fear that I might forget or altering memories of him, naturally found their way into my work. Drawing from personal experiences seems, to me, the most honest way to come up with a research topic. I do spend a lot of time searching for the right distance; not because I am worried about people knowing things about me, but because I find it important to transform or translate my experience in such a way that it becomes relatable for others.’

What are your plans for The Arctic Circle Residency you will start soon?

‘Frost, ice and snow often take on very interesting forms; they are beautiful phenomena to photograph. I have often been in the north for other residencies (though never as far as the high-Arctic) and I couldn’t help photographing the visual manifestation of cold. The people I met in these places often found my attraction to winter funny, because to them it is more of a nuisance. I would get excited about a layer of snow or ice, and they would say that it was not even that much. Their responses intrigued me. Now that the Arctic is transforming drastically, I am curious to have such conversations again. I worked a lot around mourning and loss in relation to people and now I want to investigate it in relation to landscape and cold. What about the loss of winter? Or the longing for ice crystals? I used to worry that I was just sentimental when photographing these landscapes, but now that I am going to the Artic I try to take this attraction more seriously, and dive into questions such as: How do people relate to frozen and thawing landscapes? How do changes in landscape affect us emotionally?’

Nele Brökelmann

is beeldend kunstenaar