Lost and Found Utopia Kriemann and Meessen at SMBA

Susanne Kriemann and Vincent Meessen are currently showing their latest works – One Time One Million (Migratory Birds – Romantic Capitalism) and Dear Adviser respectively – at the Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam. In the show both Kriemann and Meessen reflect on the ideology of modernism and its legacy. Although there are similarities in their approach, their works differ greatly in what side of modernism they choose to reveal.

For modernist thinkers, artists and architects, the concept of utopia was of key importance. Driven by (technological) progress and the idea of a politically, socially and culturally makeable society, modernists envisioned a perfect place, in which the inhabitants were governed by a system based on harmony and rationality. The etymology of the word utopia, derived from ancient Greek, reflects the paradox intrinsic to the modernist objective. The word outopia means ‘non-place’, while its homophone eutopia translates to ‘good place’. So on the one hand it signifies an actual place of ideal perfection but on the other this place is a non-existent vacuum, of no time and no place in particular. This ambivalence in modernism’s aim to establish a utopia is clearly illustrated in both Meesen’s and Kriemann’s works on display at SMBA.

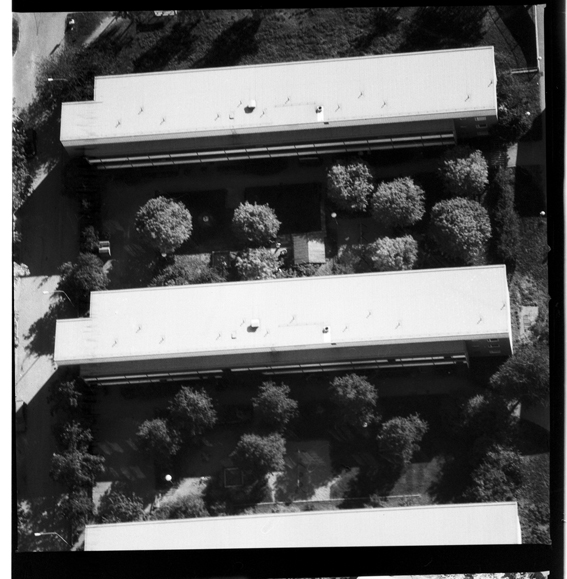

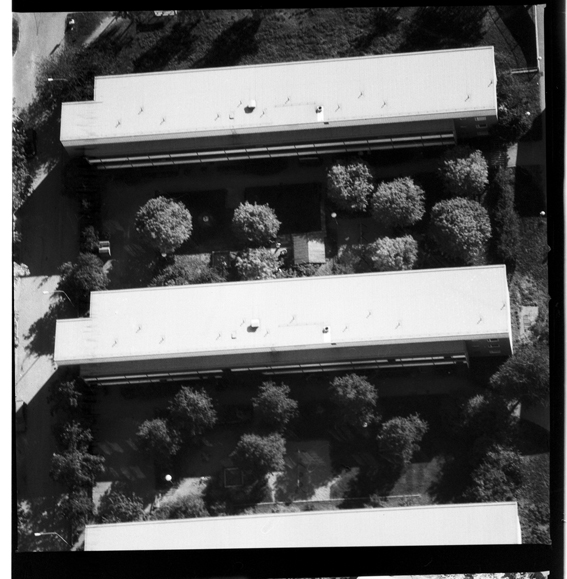

Susanne Kriemann displays 46 photographs, all taken with the famous Hasselblad camera, a symbol of modernist ingenuity and technological advancement in itself. The photographs show a variety of subjects: an airplane flying above the clouds, quietly perching or flying migratory birds, dead bird bodies from the archive of a bird museum, an aerial view of a country house and the Hasselblad camera itself. The most important part is taken up by aerial shots of the “one million” housing project in Stockholm that was executed between 1964 and 1974 in typical modernist fashion. Some photos are taken by Victor Hasselblad, the camera’s inventor, himself (or constitute photo’s of his work), others are shot by Kriemann.

The images are exhibited in a circular wooden structure. This merry-go-round type of display provides the images with a narrative continuity, enabling the viewer to make connections between the photographs. One of the most interesting parallels, both on a formal level as in regards to the content, is between the architectural grid of the modernist city and the rationalistic way the archive of the bird museum is set up.

Kriemann meticulously deconstructs the ideology of modernism in this series. Her endeavour to find motives, styles and relations between different types of modernist practice summons the utopia of modernism: a haunting illusion that everything was possible through progress. It is this illusion that Kriemann stresses, detaching the images from their original context. The (dead) migratory birds for example, refer to the fact that, from the 1980s onwards, the earlier pride in modernist housing projects fades away; the influx of the lower social classes – consisting largely of migrants – effectively turn the projects into ghetto’s. However, these allusions to the fate of such modernist projects remain rather implicit in the work exhibited.

Vincent Meessen is far more explicit in his reference to the legacy, or rather outcome, of modernism. His short film Dear Adviser shows a man – well dressed, wearing a hat – walking through the city of Chandigarh (Punjab, India).

The city was designed by Le Corbusier – who incidentally called himself advisor to the project rather than it’s architect – and built virtually in the middle of nowhere, Accompanied by a penetrating soundtrack and a voice-over alluding enigmatically to writings of Le Corbusier, Edgar Allan Poe and others, the man in Meessen’s film wanders about the city. He shows us an eclectic architectural assembly, revealing the influence of many architects beside Le Corbusier. But more importantly, since the city is no longer accessible to the public, we see a desolate city landscape. A ghost town of modernist ruins, inhabited only by this man, a few soldiers and a handful of others. The scene in which the man sits on a wall with a swastika sculpted into it, looking over a square surrounded by vast and empty concrete structures accurately represents the ambience of Chandigarh that Meessen evokes.

This city in no man’s land, lost in time, is the utopia transformed into dystopia. In an utterly compelling manner Meessen depicts the legacy of modernism, unveiling how the instruments that were to create the perfect society have become relics of a lost cause.

Kriemann’s and Meessen’s work are to a large extent complementary. While Kriemann emphasises modernism itself, deconstructing it and subtly hinting at its legacy, Meessen goes beyond that history to show its contemporary ruins. In One Time One Million we see a living utopian ideal, in Dear Adviser it has already faded away.

Overall, the exhibition at SMBA tells the story of the impossibility of utopia: once aimed for and maybe even found, but lost again and now, in a brave attempt by Kriemann and Meessen, recaptured in spectral form.

Hendrik Folkerts

curator Moderna Museet, Stockholm