Francis Alÿs A story of deception

October 9th opening in Wiels: a retrospective of Francis Alÿs, whose influence is noticed in exhibitions all over Europe this year. Jenny Wilson saw the travelling exhibition in Tate Modern this summer and gives a preview on what to expect in Brussels.

A mirage on a hot desert highway in Patagonia is the first image to greet you. The rickety camera, attempting to capture it, keeps moving towards the mirage, which is seemingly toying with us by continually moving away in a sort of seductive utopian illusiveness. The title of this work, A Story of Deception, also forms the title of the exhibition at Tate Modern, devoting 16 gallery rooms to the work of Alÿs.

This exhibition concentrates chiefly on Alÿs’ poetic acts within political situations in Mexico, Lima, Panama and Jerusalem. In addition to the many video works, the rooms are dotted with small dream-like paintings and light-box tables featuring sketches for films, projects, even Mexican newspaper articles relating to the gun, are all shown in the multiple, to the point of obsession. Everything seems like a constant rehearsal, without a definitive end.

Alÿs, born in Belgium 1959, has lived in Mexico City since 1986. His work is clearly informed by his confrontation with South America’s constant expectation and promise of modernisation only to see it strolling along with frustrating delay.

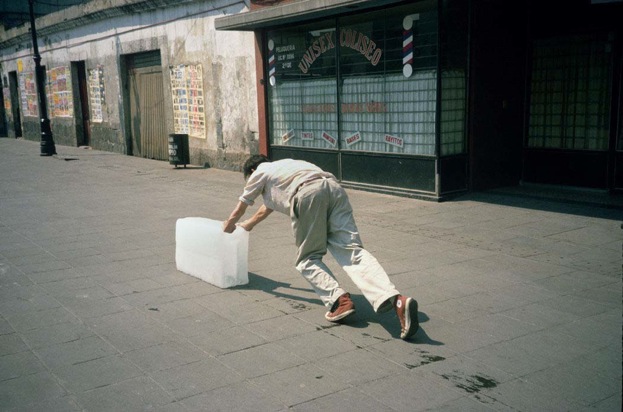

The work Paradox of Praxis I (1997) (also titled Sometimes Doing Something Leads to Nothing), shows Alÿs pushing a large block of ice around Mexico City’s centre. This humorous transience of an attempt of the outsider, steadily trying to grapple with his environment, only to see his once large block become a rather dismal, little puddle.

When Faith Moves Mountains (2002) is Alÿs’ most large-scale project to date. 500 Peruvian students, each with shovel in hand, were asked to walk in a line up a sand dune on the outskirts of Lima. Their systematic shovelling and scooping ensured that this mountain did indeed move a few centimetres. Maximum effort for a minimal result: an action with which Alÿs seems to challenge the counter-productivity of many Latin American modernisation schemes.

But fear not, it’s not all gloom and doom. Although these works inhabit a strong social critique, they are often accompanied with an accessible humour as well as a direct aesthetic likeability. There is something pleasant in these works and Alÿs seems to play with this pleasantness in a pro people, pro movement sort of way.

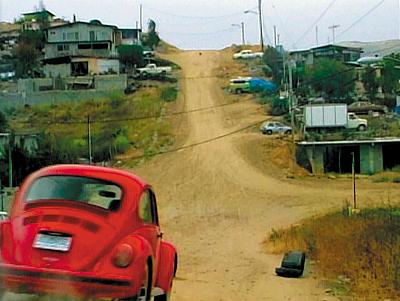

Some rooms are filled with up-beat Latin American music, particularly so in the video work Rehearsal I 1999-2001, where a red VW Beetle drives up a steep dusty road. The driver of this funny little car is listening to a rehearsing brass band. He lifts his foot off the gas pedal every time the band pauses and rolls gently back down the hill, only to continue this same futile action again and again without ever reaching the top: a veritable Sisyphus action. He is a comic slave to a sound happening somewhere else. Rehearsal and the structure of rehearsal are notions, which very much concern Alÿs. They are a continuous working towards without resolution, comparable to his continuously forcing himself into the eyes of tornados. These awe-defying actions, seen again and again, hover around the climax of chaos and it’s inescapable profundity. Is Alÿs commenting on the role of the artist and his inability to order what comes at him?

There is often a subdued monotonous aesthetic to the works of Alÿs, yet there is no question of dullness. His poetic actions skirt the absurd, yet are also rooted in global social issues relating to migration, urbanism, economics and borders.

The Green Line is a work stemming from an action Alÿs carried out in São Paulo in 1995, where he dribbled blue paint from an open paint can as he walked from the gallery, around the city and back to the gallery again.

The armistice border in Jerusalem, known as ‘the green line’, was mapped out with a pencil at the end of the war between Israel and Jordan in 1948. This remained the border until the Six Day War in 1967, after which Israel occupied the Palestinian-inhabited territories east of the line. Alÿs, with his nonchalant walk, maps this very border whilst dribbling green paint behind him from an open tin. Onlookers stop and stare as they notice this tall Belgian and his strange trail. Should they say something? Ask something? Alÿs remains carefree and unconcerned by the many gazes that follow him. His reflection that ‘sometimes doing something poetic can become political and sometimes doing something political can become poetic’ is really the core of this exhibition: the crossing between poetics and politics. Poetry can never be politics and politics can never be poetry, as they ultimately cancel each other out. Alÿs plays with this by gently turning these two spaces around to face each other. It is precisely this action of play, which prevents his work from being a political statement alone, and as such it ultimately remains in the realm of the poetic.

This exhibition is well worth seeing. Visitors are lured and linger. It is a world of quiet absurdity sucking you in. Upon leaving the exhibition the suggested deceit is comforted by the lulling Song for Lupita (1998): an animation of a woman pouring water from one glass into another. The accompanying song softly coos ‘Mañana, mañana’ (‘tomorrow, tomorrow’).

Francis Alÿs, A Story of Deception…:

– 15 June 2010 – 5 September 2010, Tate Modern, London

– 9 October 2010 – 30 January 2011, Wiels, Brussels

– 8 May 2011 – 1 August 2011 MoMA, New York

Some of the discussed video works can be viewed and downloaded on the website of Francis Alÿs.

Jenny Wilson