Photograph made by the author during the Weg Die Muur walk.

Can Walls Have Windows? – Weg die Muur, an artist walk through Amsterdam West – Walks/Wandelingen #2

While it would usually be considered rude to snoop around other people’s windows, artist Aimée Zito Lema invites you to do just that. The research-based artist walk Weg die Muur (Tear down that wall) leads through two neighbourhoods of Amsterdam West, tracing the dichotomy between old and new through a series of curtains inspired by archival materials. Kaylie Kist embarked on a walk from the Spaarndammerbuurt to the Houthaven, peeking into windows along the way, and was overwhelmed by the history, the stories and the sun.

It’s the beginning of an exceptionally warm September when I arrive in Amsterdam, ready to explore the sun-soaked streets through the self-guided walk developed by Aimée Zito Lema (1982). Made in collaboration with Cargo in Context and Museum Het Schip, the walk covers two neighbourhoods in the west of Amsterdam: the old Spaarndammerbuurt and the modern Houthaven. The dichotomy between the old and the new already hints at the title of the walk: Weg Die Muur (Tear down that wall).

Photograph made by the author during the Weg Die Muur walk.

Reconciling the old and the new

It was whilst living first in the Spaarndammerbuurt and later in the Houthaven, that Zito Lema discovered an archive that inspired her. The archive preserves fifty years of history of the Spaarndammerbuurt and the Houthaven, spanning from 1940 to 1990. The material in the archive consists of everyday street life photography and noteworthy architectural images, but also documents the many demonstrations that took place there – protests against rent increases, evictions, and poor housing conditions. Through Zito Lema’s detailed and multi-layered research, accessible via the project website, I learn that the Spaarndammerbuurt has a long history of cultural and militant expression, and was historically known as ‘the red’ neighbourhood for its widespread support of communism.

In recent years, the Spaarndammerbuurt has succumbed to gentrification, but its timeworn residential areas act as a stronghold for the working class. The Houthaven by contrast has its historical origins as a timber processing port. Due to its demise at the end of the twentieth century, coupled with a growing housing shortage, plans were forged to transform the former port into a large-scale residential area, creating a new, parallel community. And so, the gulf between the old and the new was created.

After living in the Spaarndammerbuurt for seven years, Zito Lema moved to the Houthaven. In her old neighbourhood, she had witnessed familiar social characteristics gradually disappearing, while in de Houthaven a new and more luxurious vision of the city began to appear, as if the demise of one fed the rise of the other. Zito Lema understands her project as a departure point that could contribute to the improvement of social cohesion. By applying her archival discovery, she felt it would help to not only preserve the historical memory of the many social and cultural expressions but also to create a collective space for more recent and new community experiences.

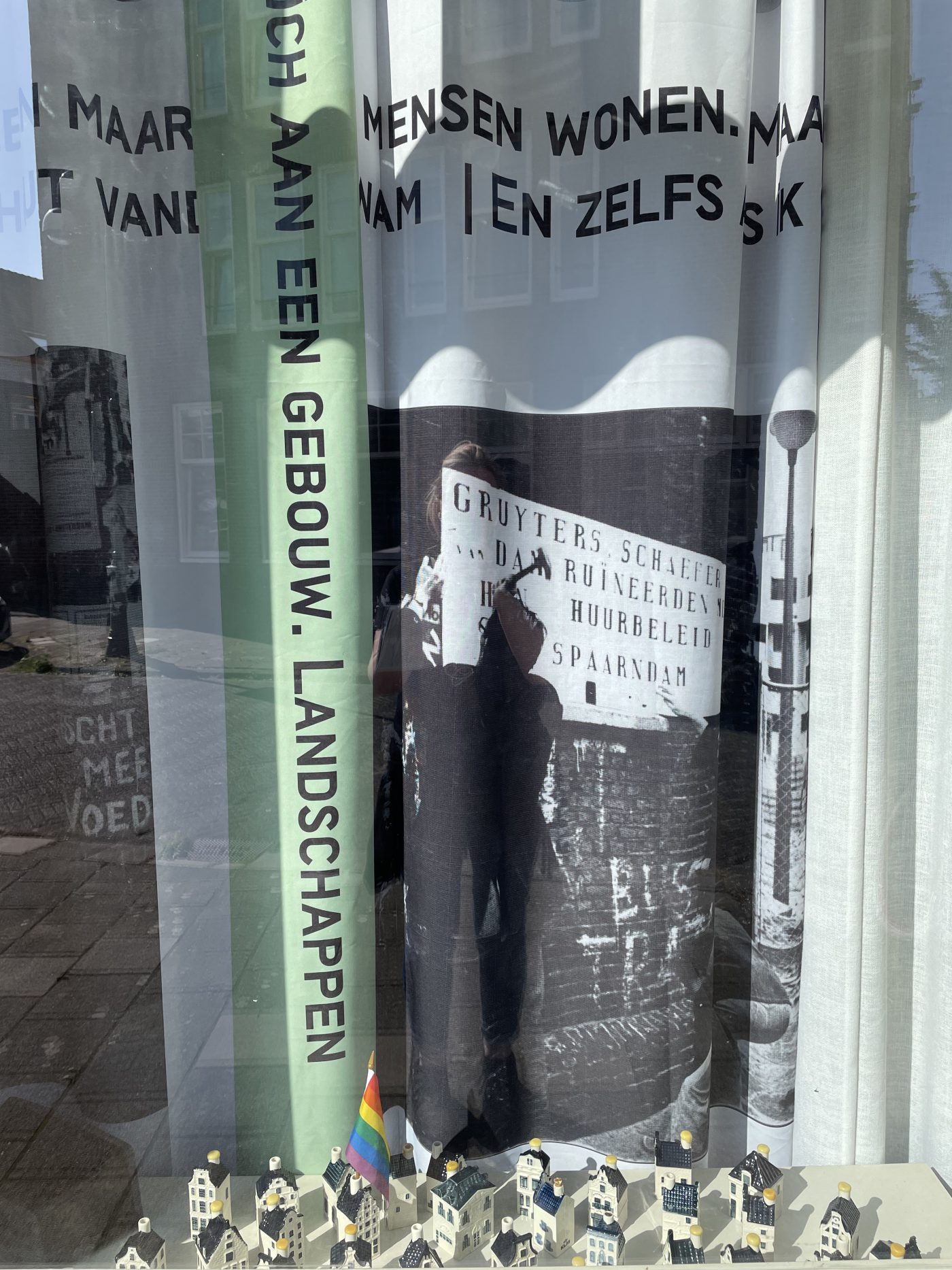

Zito Lema’s curtains not only provide the opportunity to peer into people’s lives but to examine fragments of history, situated in and around the frame of the window itself.

Photograph made by the author during the Weg Die Muur walk.

Photograph made by the author during the Weg Die Muur walk.

Spaarndammerbuurt

The walk itself begins at Museum Het Schip, an impressive vessel of architecture that has a long been associated with social housing within the community. I pick up a guide map, designed in collaboration with Vanessa van Dam. The journey weaves its way along the pavement, steering me past forty-one windows dotted in and around both neighbourhoods. Each window shows an artwork in the shape of specially designed and printed curtains featuring archival images and quotes from more recent interviews with residents. The curtains juxtapose two different timestamps, indicating the social fabric Zito Lema wants to depict.

Hembrugstraat 34B. Turning right, I spot a window clad in printed drapes. These are no ordinary curtains. Woven into their fabric are marching crowds waving protest banners, with layers of superimposed text. ‘I started cleaning’ one proclaims. It made me wonder who and what was being cleaned? I make a link to gentrification, but it could equally be a statement of profession, either way, the curtains begin to act as portals of insight.

Zito Lema explains that curtains offer a porous boundary between internal-external worlds, between public and private. Her curtains not only provide the opportunity to peer into people’s lives but to examine fragments of history, situated in and around the frame of the window itself. I appreciate this choice, the possibilities that curtains offer: insight, exposure, and sometimes concealment. They’re either open or shut and create a clear dividing wall between inside and out. In relation to the Spaarndammerbuurt and the Houthaven, Zito Lema reflects on these curtains as a symbolic wall and invites communities to come together and break down these metaphoric walls of difference.

Small QR codes can be found by some of the windows, which, upon scanning, reveal transcribed conversations of community members, including an Iraqi tailor, an artist, an activist, an architect, a school principal, a restaurateur, a pastor, shopkeepers, long term residents and newcomers. One of the more surreal stories recalls the request made in 1954 by staff members of the children’s bathhouse in the Zaanstraat. They wrote a letter to President Pandit Nehru of India, claiming that it would be beneficial for the neighbourhood children to receive an elephant. Unbelievably, Nehru granted this wish. The children of the Spaarndammerbuurt received a young male elephant, named Murugan. The elephant arrived by ship and was delivered via the port in the Houthaven. The curtains in the windows of Spaarndammerstraat 72 document this event.

I’m reminded of Foucault’s description of how new insights offer different ways of seeing the world: ‘my job is making windows where there once were walls’.

Photograph made by the author during the Weg Die Muur walk.

Photograph made by the author during the Weg Die Muur walk.

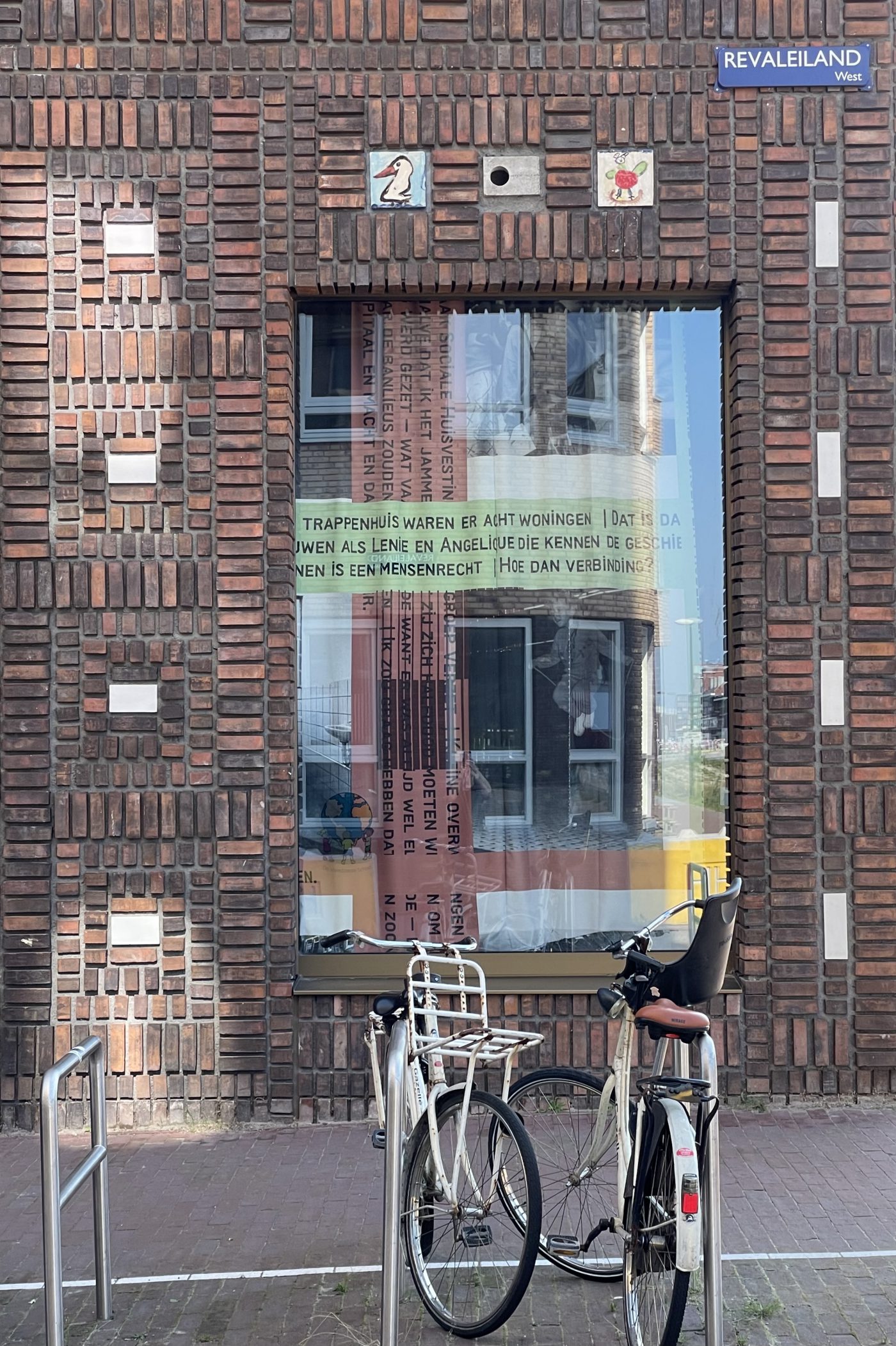

Houthaven

I eventually complete the first twelve windows of the Spaarndammerbuurt and cross the dividing line, the main road that carves its way between the two locations. I sense an immediate difference. Shiny steel sculptural forms mark the threshold to Houthaven, giving way to recreational space in the form of grassy parks, open walkways with limited car access and an evolving skyline of airy lofts and modern multi-functional accommodation. I reach the new school that sits close to the boundary line, which houses children and families from both neighbourhoods. Zito Lema points to this school as one of the most hopeful spots for cohesion, collectivity and shared experiences – through the collective education and growth of future generations.

There are more windows than curtains on this side of the street. Plush interiors and landscaped gardens sit between half-finished building plots, dry canal beds, cranes, and other heavy-duty building gear. I try to cover all seventeen windows in the Houthaven but building work hampers access to some. Whilst the gloss of the new feels like wet paint, it somehow lacks the soul of the Spaarndammerbuurt. Everything feels further apart. I begin to feel like I’m ticking off windows, my body moves indifferently along the exposed walkways.

I realise that the experience of this walk can come to mean different things depending on your point of entry. For those living in one of the neighbourhoods, it may highlight histories, connections, streets, places, and voices known or maybe unheard within the community. But to the outsider, access and maybe understanding of the dichotomies of these places may come at a different pace. Zito Lema’s multi-dimensional windows into time, history and personal expression cannot be delivered for immediate access to all. Like their content, they are complex, layered and much like social change she explores, it is built up in thin layers over time, and remains dynamic. I’m reminded of Foucault’s description of how new insights offer different ways of seeing the world: ‘my job is making windows where there once were walls’. Whilst Zito Lema may not have yet succeeded in tearing down the wall, she has opened windows and new ways of viewing these neighbourhoods.

Weg Die Muur starts at Museum Het Schip in Amsterdam and will be accessible until the 17th of October 2021. More information on the walk, the accompanying public programme and the project documentation can be found on the project website.

Kaylie Kist

is an artist and writer