Some highlights of the MVRDV maquettes. Collection Het Nieuwe Instituut. Photo by E. Roelsma

A double exercise – MVRDVHNI: The Living Archive of a Studio

Situated right at the top of Het Nieuwe Instituut in a former office space, the current exhibition of MVRDV’s practice looks directly out towards the Depot of the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, the latest instagrammable landmark in the architectural studio’s eclectic oeuvre. Colin Keays visits a refreshing double exercise in re-interpreting an archive and exhibiting an architectural retrospective.

I have to admit I’m a little allergic to monographic architecture exhibitions. All too often, they avoid any critical analysis of the body of work in order to protect the interests of developers, clients or the reputation of the architects themselves, and as a result end up as a dry and unoriginal display. Refreshingly, MVRDVHNI: The Living Archive of a Studio opening at Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam is as much of an exercise in re-interpreting an archive as it is an architectural retrospective. Framed as a dialogue between an architectural practice and the institution that has hosted their archive since 2015, it attempts to breathe new insights into the three decade long history of one of the most prominent Dutch architectural studios by combining a display of their work with experimental interpretations and alternate readings.

As a studio, MVRDV have built a name for themselves with playful gestures and crowd-pleasing landmarks that border on the absurd, such as a disneyfied reference to a UNESCO world heritage site in Zaandam, or colossal rendered graphics of fresh produce printed onto the ceiling of Rotterdam’s Markthal. While the exhibition is not short on some of these more iconic designs, by revisiting the first 400 of MVRDV’s projects stored in the archive at Het Nieuwe Instituut, the exhibition offers visitors a behind the scenes glimpse into some of the thinking processes that drive this pop-architecture with early sketches, working drawings and even email correspondences.

[blockquote]MVRDV have built a name for themselves with playful gestures and crowd-pleasing landmarks that border on the absurd, such as colossal rendered graphics of fresh produce printed onto the ceiling of Rotterdam’s Markthal

Impression of the exhibition MVRDVHNI The Living Archive of a Studio, Het Nieuwe Instituut 2021-2022. Photo by Aad Hoogendoorn

Impression of the exhibition MVRDVHNI The Living Archive of a Studio, Het Nieuwe Instituut 2021-2022. Photo by Aad Hoogendoorn

Impression of the exhibition MVRDVHNI The Living Archive of a Studio, Het Nieuwe Instituut 2021-2022. Photo by Aad Hoogendoorn

The space of the exhibition and timing of its opening is clearly a conscious choice. Situated right at the top of Het Nieuwe Instituut in a former office space, the exhibition looks directly out towards the Depot of the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, the latest instagrammable landmark in MVRDV’s eclectic oeuvre. As an experimental new home for the Boijmans’ own archive of fine art and design, there’s a subtle provocation here to question how an architectural archive might also be opened up and exhibited to the public. Meanwhile, the carpeted floors of the former 1990s office on the sixth floor of HNI – while normally an unconventional choice for an exhibition space – allow for a play on the aesthetic clichés of an architectural studio without coming across as too tacky. As a result, blue foam maquettes and material samples are comfortably displayed with the same confidence as finished models and photographs.

Overall, there is quite a clear distinction between which parts of the exhibition were conceived by MVRDV and which by HNI, with separate exhibition designs that occasionally clash as this dialogue becomes a bit heated. MVRDV display their work on three rows of desks containing models of some of their most famous works alongside unrealised designs, categorised under three broad and PR-friendly themes of Human, Green and Dream. In parallel, HNI addressed this with a series of interventions or ‘cross sections’ around the peripheries of the space with titles such as Behind the Cover, Happiness Filter and Blue Foam Models.

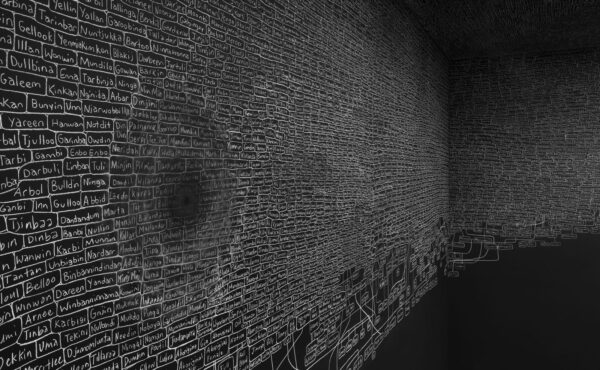

These include a series of oral histories revealed through video interviews of different voices from MVRDV’s history displayed on small tablet screens. By including footage of former interns and collaborators sharing their memories as they open up archival boxes, traditional notions of authorship are upturned as these valuable voices can then be added to the archive once the exhibition is complete.

One of the most distinctive interventions is a series of six digital ‘tools’ from externally commissioned artists, designers and researchers which give new insights into the digital archive and leave room for more critical evaluations

One of the most distinctive interventions is a series of six digital ‘tools’ from externally commissioned artists, designers and researchers which give new insights into the digital archive and leave room for more critical evaluations. Focusing on emails and communication material from MVRDV over the years, Giacomo Nanni and Francesco Morini’s tool analyses a text-based dataset and translates this into an interactive visualisation of the frequency at which words occur over time. While some users might filter projects by location, material, or theme, it could also leave room to dive deeper into references (or lack of) to the financial, social and political side of architecture. Meanwhile, their second tool playfully uses an A.I. trained on this dataset to generate new sentences and automatically tweet them, inadvertently highlighting some of the absurdity of architectural PR and communication to which MVRDV are not immune.

Namelok chose to focus on the imagery used by MVRDV, specifically the cutout people populating their renders and visualisations. By analysing factors such as age, race, gender and clothing, they ask ‘what does an MVRDV society look like?’ and translate their findings into five portraits. In doing so, this opens up broader questions of normativity in architectural representation that has a relevance beyond just MVRDV.

Next to this two dimensional representation, artist Alice Bucknell delved into the 3D model archive to create ‘Zonamata’, a satirical video game and accompanying short film with a script generated by artificial intelligence. Players can immerse themselves in a speculative spatial environment consisting of fragments of MVRDV’s finished and unrealised projects, bringing the digital archive to life while allowing players to explore their dystopian surroundings, featuring avatars of architects Rem Koolhaas, Bjarke Ingels and Winy Maas himself.

Impression of the exhibition MVRDVHNI The Living Archive of a Studio, Het Nieuwe Instituut 2021-2022. Photo by Aad Hoogendoorn

Impression of the exhibition MVRDVHNI The Living Archive of a Studio, Het Nieuwe Instituut 2021-2022. Photo by Aad Hoogendoorn

It’s a shame that these interventions end up tucked away at the end of the exhibition, considering that such experimental formats are so rarely featured in architectural presentations and could have benefited from being more prominent. At times the overall exhibition therefore comes across as a little awkward: on one hand an experimental exercise in research that is typical of Het Nieuwe Instituut, on the other still fitting the brief of being a retrospective exhibition of a prominent studio. Overall though, treading a line between the two likely pleases both camps: those interested in learning from the vast knowledge gathered by MVRDV in their three decade history, and those keen to scratch below the surface.

MVRDVHNI: The Living Archive of a Studio is on view at Het Nieuwe Instituut until the 4th of September 2022

Colin Keays

is spatial designer en researcher