A Memoir Polemic, Tirdad Zolghadr on his new book Traction

“Traction argues that contemporary art is defined by a moral economy of indeterminacy that allows curators and artists to imagine themselves on the other side of power. This leaves us politically bankrupt, intellectually stagnant, and aesthetically predictable.” The back-cover of the most recent book by independent curator and teacher Tirdad Zolghadr reads as the start of a political pamphlet. A very personal pamphlet at the same time. Zolghadr treats his own exhibitions and teaching experiences as cases that enlighten his point, while discussing his view on curating, art schools, the economic position of the artist, the role of the image, of the location of art, etcetera. He generously credits the people with whom he have been working with in various institutions and on various occasions, thinkers like Thomas Keenan (Bard College, U.S.A), Suhail Malik (Goldsmith’s, London) and curator Maria Lind, while giving an occasional sneer to others such as Hans Ulrich Obrist, and at the same time nagging at curatorial theory since it can hardly be called interesting to anyone in the arts. This teasing approach makes this curatorial theory book quite a fun-read.

Zolghadr is informed by the oblique perspectives of having had experience in such diverse cities as Berlin, Ramallah, Taipei or Tehran. From there, he elaborates on a particular shortcoming that haunts curatorial and teaching practices, but that is usually not addressed: the position of power within that practice.

Jelle Bouwhuis: Two terms reoccur throughout the book: ‘indeterminacy’ and ‘moral economy’. Can you explain these terms in a nutshell to the Metropolis M reader?

Tirdad Zolghadr: ‘Moral Economy is a term coined by sociologist Didier Fassin, and I borrow and bastardize it to describe contemporary art. Moral, because we work in a field that is defined by a moral horizon too, even though we assume contemporary art is there to always deconstruct our very own values and beliefs. Economy points at circulation and distribution – of works, ideas, jobs – and the fact that some places are better supplied than others. Indeterminacy has a long genealogy stretching from the Greeks all the way to John Cage, and to analyze it soberly came as something of a revelation for me, a U-turn moment where it all started. It was through working intensively with Suhail Malik. You tend to think that indeterminacy is the fundamental condition in contemporary art. Especially for me, with my experiences of working in places like Palestine and Jordan and myself coming from Tehran, this idea of open-endedness in contemporary art appears as the best-case scenario to achieve. But thanks to Mailk I realized it is actually part of the problem. The idea of the open-ended access, something that I have fought for so hard and at many levels, doesn’t really serve any political purpose anymore.’

Aren’t it exactly experiences from such locations that constitute the eye openers, especially to us in North-West Europe, conformed to our generic habitus of blue chip art infrastructure?

‘Palestine became the test case after I had moved there in 2013. There I got an insight that I discuss in the chapter about art images and installation shots. We curators/educators are used to communicate through installation photographs. But these images are related to the white cube environments that house the art in the first place. Many BFA students I taught were well versed, but many from the humanities had never seen an exhibition before and didn’t have any experience with that kind of space. They were not at all seduced by the attraction that attaches us to them, like a Christ in a church – of something sacred. They just saw a white room, a living room maybe, but definitely not this ideologically charged space.

If I have to describe Indeterminacy in brief, thus open-endedness and the idea of the audience that we say we are doing it for, it boils down to disengagement with power. The idea that things are just open enough for you to disavow your expertise and the expertise of your audiences. That just stumbles upon the curatorial work and everything that it mediates in that radical moment of indeterminate possibilities. Which makes you as a mediator let leave things open, and while doing so imagine an audience that is open to everything. I push against that. I would suggest to identify with power. Because we do have authority, we do have expertise, we are the ones with the means in contemporary art.’

But you write form the perspective of an independent curator/educator. How do you imagine institutional curators to cope with that, as it almost seems a mission impossible giving the way that they’re entangled in issues of institutional strategy exclusively?

‘Take, in the Dutch context, Charles Esche. He is the perfect example of someone beyond indeterminacy. He has an agenda. He is a Union guy, a social democrat. He doesn’t apologize for the power he has as a director, he makes no compromises. But in all the discursive output and exhibitions under his supervision, there is still a shunning away from didactics. I’m not judging on that, because maybe there is a politically tactical reason for that, but I can’t imagine that there is no director under the sun who is not able to find the political maneuvering space to be didactic. Vasif Kortun has turned the Istanbul art scene completely on its head. But you will still have to look out for the moment that he identifies with that power status and asks where to go from there.’

I associate Indeterminacy strongly with the situation we have in which institutions, for instance museums, that are semi-public, yet act and talk like private institutions, in a way abusing the indeterminacy of the arts for artistic strategies that are absorbed in finance and beyond public control. It would be necessary to create a stronger awareness on behalf of the audiences in order to turn that into a more determinate, or transparent, enterprise.

‘For a large part, it is our generation that is to blame to have been painting that picture of Indeterminacy for so long. But even if we’re allowed to say that institutions have been bullied into this corner by the political economical establishment, it strikes me that if we’re sitting alone somewhere, having a drink or so, the best-case scenario that you will hear is pretty much Indeterminacy as we know it. We don’t even fantasize about something that goes beyond that. And that is the problem. Instead we should identify with power, not disengage with power but rather use it to form an audience ourselves.’

Would it be a solution that the art world fragments into much smaller particles, where participative models in small institutions can be established, rather than expecting anything from these entangled power conglomerates? So the identification is rather with the position of an independent curator than a institution.

‘I give you another example. I teach at the Dutch Art Institute. It is directed by Gabriëlle Schleijpen, who is a political genius. But she doesn’t teach at the DAI. The curriculum at the DAI is all about critical theory. But she herself is not part of the curriculum. If it was up to me (but it isn’t), I would make her position part of the teaching, so that we could discuss where the power relation sits in the critical theory about Indeterminacy we teach. The political strategies of someone like her should be active part of the theoretical discussion. And if the directors that are now decision makers, like the Richard Armstrongs, the Klaus Biesenbachs, would make the decisions to be more determinate, it would make their actions and policies more transparent. If the people in power would embrace something that goes beyond Indeterminacy, if the new moral economy would be adopted within the rooms that are thick with cigar smoke, things would shift decisively, at least that’s my conviction.’

Will such people go into that themselves or do they need to be forced?

‘We are witnessing a fragmentation; the art world will split in many different worlds. Places such as the Stedelijk Museum for instance will gravitate closer to something we know from Hollywood. We will end up with different moral economies in contemporary art. In general I believe we are in a political situation in which people are frustrated enough to want to have things differently.’

How would you put your ideas of Indeterminacy and transparence in the field of vision of larger audiences?

‘The places where these ideas are put into practice are of small to medium scaled. From my own experiences these vary from the ‘Monogamy’ exhibition I curated at CCS Bard galleries is an example (2013, featuring Gerard Byrne and Sarah Pierce who are husband and wife, one of the working examples in the Traction – JB) to my work in the context of the 5th Riwaq Biennale (Palestine, 2014; this edition was critically distanced to the Qalandiya International but in 2016 the two seemed to have been completely merged into the latter – JB). Now I go doing smaller and bigger places. Most of the voices sympathetic to my agenda I find with people who invest in teaching and this will undoubtedly lead to a generation that will have a more robust agenda than mine. Another example is my position as associate curator at KW in Berlin starting in 2017 or my directorship of the Bern Summer Academy; at both places I will need to practice what I preach. At larger institutions I see, very slowly, new types of mission statements that enable to move away from the false populism we’ve been hearing for so long now. You also see artists and curators working in new alliances that are less individualistic, but we are still too far away from a non-indeterminate moral economy for me to be able to clearly visualize its future.’

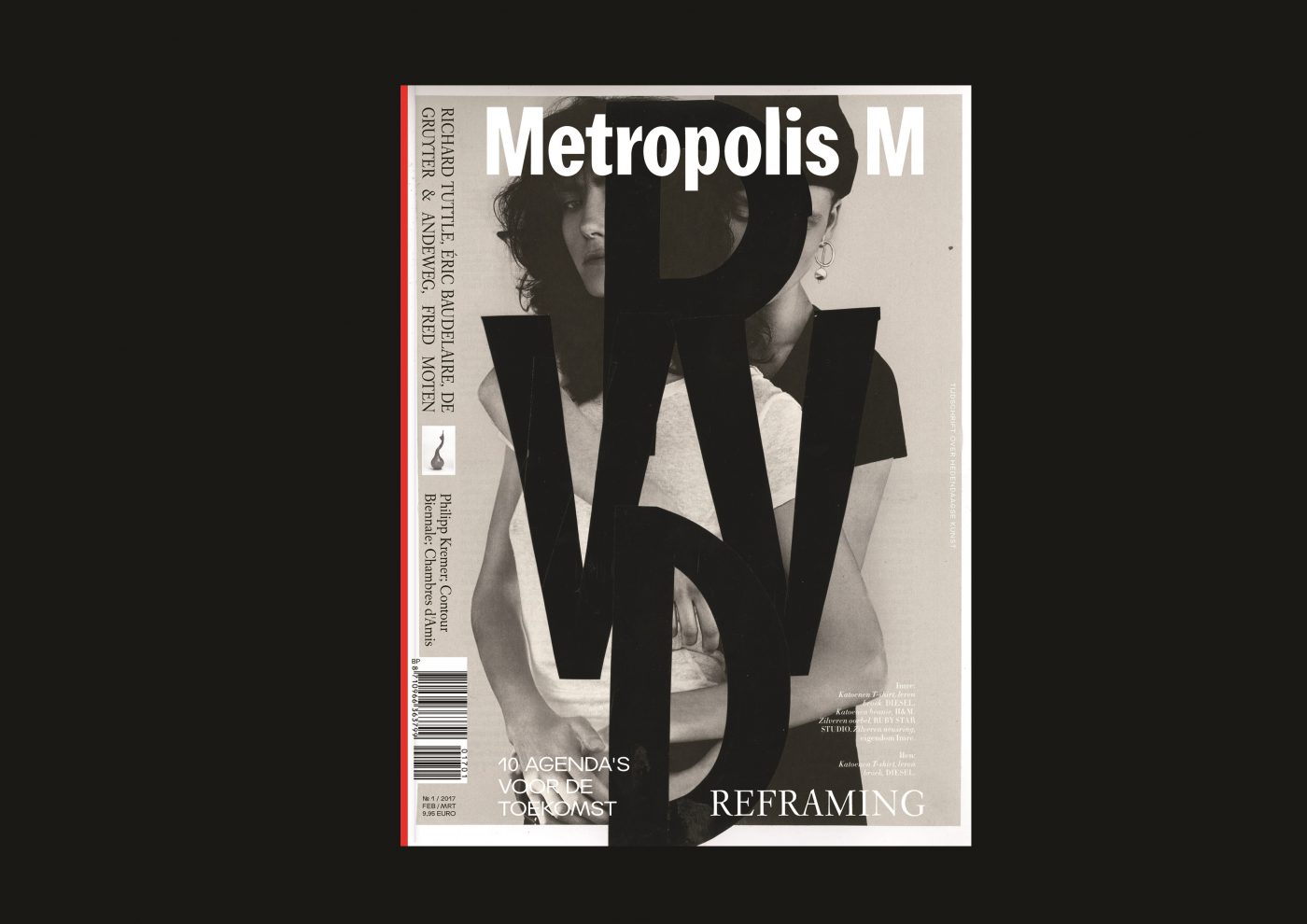

THIS TEXT WAS PUBLISHED IN A DUTCH TRANSLATION IN METROPOLIS M No 1-2017 REFRAMING.

Jelle Bouwhuis is art historian and curator-at-large Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

Tirdad Zolghadr, Traction, Berlijn: Sternberg Press, 2016, ISBN 9783956792038

Jelle Bouwhuis

PhD researcher Modern and Contemporary Art Museums, Globalization and Diversity, VU Amsterdam