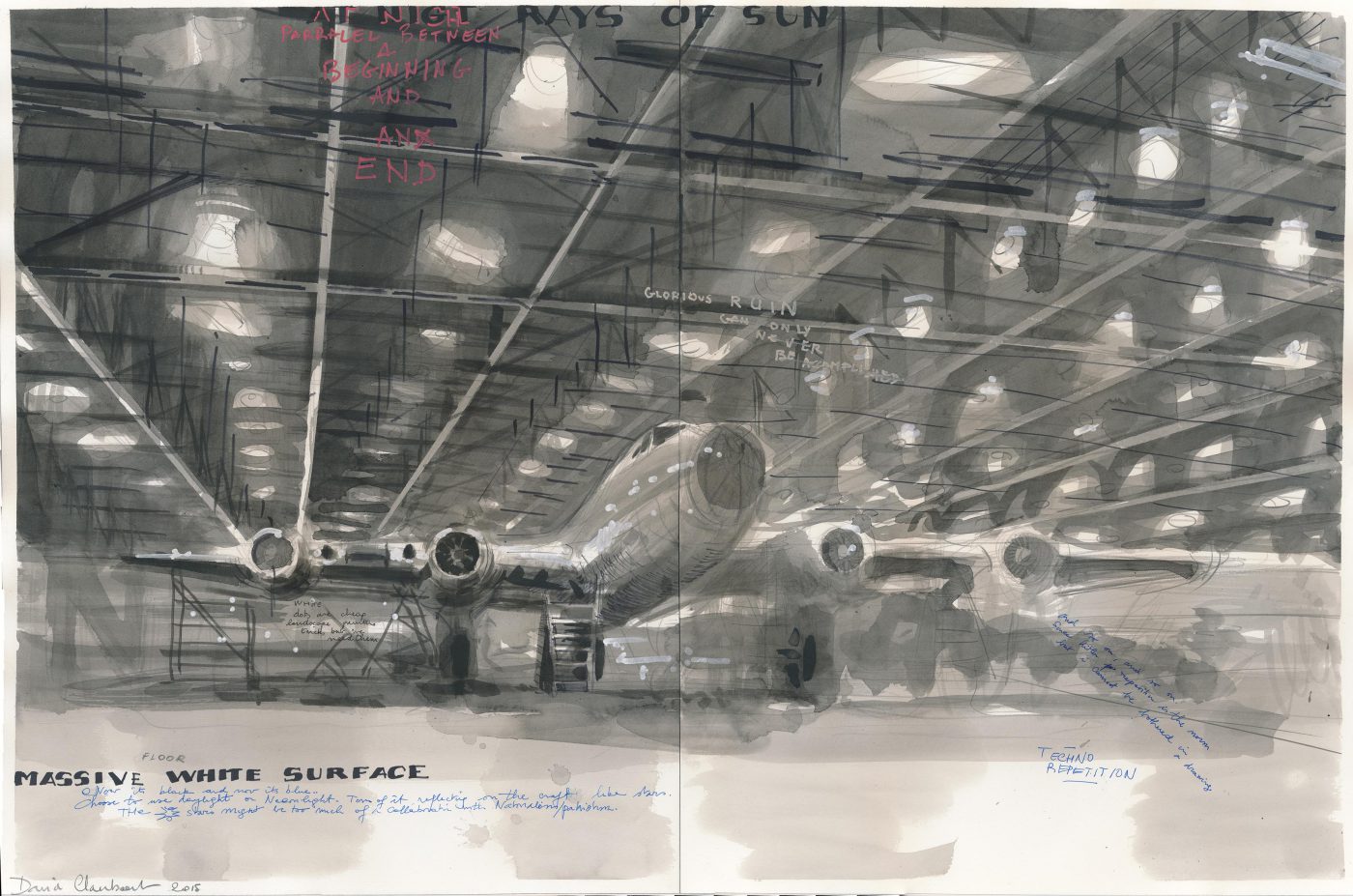

David Claerbout, Aircraft (FAL), 2015-2021. Courtesy de kunstenaar en Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp; Esther Schipper, Berlin; Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich; Sean Kelly, New York; Pedro Cera, Lisbon. © c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2021

Pursuing the Madness of the Image: A Conversation with David Claerbout

David Claerhouts new exhibition at De Pont museum in Tilburg spans almost two decades of artistic practice in storyboards, drawings and video works. Ory Dessau traveled to Tilburg to speak with Claerhout about his uncanny works in which he attempts to grasp the passing of time, and blur the differences between reality and illusion.

I met David Claerbout on the occasion of his current exhibition at De Pont Museum in Tilburg, which was built around the new work Aircraft (FAL) (2021), a conceptually adventurous video installation centered on an image of an airplane. We talked about several of Claerbout’s earlier works, such as The Pure Necessity (2016) and Olympia (2016), which was also included in the presentation in Tilburg. Although each of these works appears distinctly different, our conversation revealed that all of them reflect Claerbout’s fascination with time, memory, hallucinations and madness. Each in their distinct way, the works blur the differences between reality and illusion without falling into the trap of a dreamy, surrealist atmosphere. They render reality and illusion as indistinguishable qualities of the same experience, the experience of our contemporary world, of madness.

David Claerbout, Shadow Piece, videostill, 2005. collectie De Pont museum Tilburg.

David Claerbout, Shadow Piece, videostill, 2005. collectie De Pont museum Tilburg.

David, I would like to start with The Pure Necessity. For this video work, which was projected onto the façade of Kunsthaus Bregenz during your solo exhibition at the museum in 2018, you adopted the imagery of Disney’s The Jungle Book. However, rather than repeating the narrative of a little boy who lives in the jungle and encounters various speaking animals, you have abandoned the story and dehumanized the animals. Instead of speaking, dancing and singing, the animals behave as their species would do naturally. The movie is almost a nature documentary featuring Disney’s animals. How would you describe the conceptual scope of The Pure Necessity?

I thought a lot about The Pure Necessity before I even began its actual production. The Pure Necessity is not appropriation art; it uses the imagery of The Jungle Book, Walt Disney’s animation movie from 1967 based on Rudyard Kipling’s book The Jungle Book (1894), but from there it takes off somewhere else. Initially I was planning to appropriate the movie and change small things for my adaptation. I was confident that I would be able to do so cleverly and with minimal effort, but it turned out to be completely the opposite. It was a nightmare that I would never ever want to repeat and that almost brought my studio to bankruptcy.

Was your intention to throw us back to the late 1960s, the time the movie was released, or were you more interested in immersing us in the timeless paradise depicted in the movie?

The great advantage of working with pre-existing scenery like that from The Jungle Book, is that you basically work with memory. Everyone in the West already has an idea of the story and can visualize images from the movie. There are many poetic and thematic levels in the movie that I exploited, such as the typical post-WWII narrative of the strong protecting the weak. There is an outspoken social message in The Jungle Book: even if you do not belong to us there is a chance we might belong to the same family. Also, every character in The Jungle Book plays a typological role from the typical post-WWII narrative: the phlegmatic big guy, the clever engineer, the snaky fellow, etc. In fact, the movie presents a hegemonic set of characters that doesn’t challenge the cultural status-quo.

Your interventions in the movie demonstrate the ways you interpret it, but concurrently your interventions carry the movie and maybe even animated imagery in general, to a new territory.

In a way, I wanted to suck the life out of The Jungle Book and remove most of the animation, the energy, all the sugar, so to speak. To bring it to a state of exhaustion. I removed all the protein the movie was feeding generations after generations of viewers. I slowed down the rhythm, the tempo of the sequences. The result is uncanny, like looking at a grainy reproduction of something you thought you knew but no longer recognize, something on the verge of defamiliarization.

You don’t just exhaust the movie, you somehow exhaust our prior knowledge of the meaning of being exhausted. Your modification of The Jungle Book has a strange combination of lifelessness and liveliness, of inertia and exertion.

When watching the movie, at a certain moment things flip, and within this listless environment that I recreated, all of a sudden one begins to feel the weight of the labor invested in this recreation, observing how negativity becomes positivism, and vice versa. This disorientation, this indecisiveness if you will, is very important to me.

I guess that these dynamics can also help us understand Aircraft (FAL), your new video work centered around the image of an airplane. From the video, one cannot determine whether the airplane is hovering or immobile; the images push us into a sort of cognitive limbo where we cannot decide the extent of its virtuality and the extent of its physicality.

David Claerbout, Aircraft Massive White Surface (second study), 2015. collectie De Pont museum, Tilburg. Foto Peter Cox, © c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2021

The airplane seen in Aircraft (FAL) represents many things simultaneously, and this simultaneity is crucial to the work. The airplane is shown in a hangar, but the hangar does not appear to be an active hangar – in fact, it could also be regarded as a museum. Although the airplane is shown indoors, it is also in the air and in motion, as we do not see its wheels or the movement of its engines. At the same time, the scenery suggests the airplane is neutralized or under construction.

The work is an attempt to let viewers encounter aggressive images in an un-shocking manner. I don’t believe in the liberating effect of shock-images, which is why I prefer to work with virtual images. By virtual I don’t mean non-existent. The virtual has nothing to do with the object not being there. Instead, it implies that the object can no longer go back to where it came from, nor arrive to where it was seemingly intended. To me, the virtual is always, already, in-between.

The virtual has nothing to do with the object not being there. Instead, it implies that the object can no longer go back to where it came from, nor arrive to where it was seemingly intended. To me, the virtual is always, already, in-between.

David Claerbout, Aircraft (FAL), 2015-2021. Courtesy the artist and Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp; Esther Schipper, Berlin; Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich; Sean Kelly, New York; Pedro Cera, Lisbon. © c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2021

David Claerbout, Aircraft (FAL), 2015-2021. Courtesy de kunstenaar en Micheline Szwajcer, Antwerp; Esther Schipper, Berlin; Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich; Sean Kelly, New York; Pedro Cera, Lisbon. © c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2021

Another way to understand the work would be emphasize the component of memory in it. Aircraft (FAL) represents my endeavors to study the active connections between the retina and the visual cortex – how memory functions there, and how our memory is constructed along the exact same pathway as our real-time vision. Memory and vision share one highway in our brain. It is a possible way of explaining what we call madness, of seeing something which is being permeated by something else which is not outside ourselves. Although I see Aircraft (FAL) as a work that stands on its own, it also fits into a pattern of recurring research in my work about the interchangeable pattern of memory and vision, from memory to vision, and back again.

I guess that this is what distinguishes you from an artist like Seth Price. Both of you thematize and conceptualize the function of the photographic image in the digital era, but while he is interested in the impact of distributing and circulating images through communication networks, you examine images as a synonym to pure vision.

Indeed, I am not necessarily invested in laying bare the mechanics and the ideology of our systems of visualization, though I believe my work can be useful when questioning the truth value of images nowadays.

So in your work you interpret perception and hallucination as interchangeable. You do it in Aircraft (FAL), but also in Olympia, whose full title reads Olympia (The real time disintegration into ruins of the Berlin Olympic stadium over the course of a thousand years).

David Claerbout, Olympia Stadion (impression of rain), 2015. collectie De Pont museum Tilburg.

The video work Olympia is a photographic reconstruction of Berlin’s Olympia stadium, designed by Werner March for the 1936 Olympic Games, which avoids the use of camera. The video reconstructs an image of the site based on real-time data communicating the conditions of light, weather, etc. What you see is real and fake at the same time. It is programmed to last for a thousand years, and it keeps working even when there is no one to watch it.

Within the framework of the discussion about vision and hallucination you just outlined, would you also consider the words ‘memory’ and ‘hallucination’ as interchangeable?

Certainly, to internalize the hallucinatory component of perception is a difficult endeavor, for all of us. Personally speaking, in my work I strive to establish a steady platform on which I will be able to juxtapose the madness of the photographic image with the casual, daily, innocent visual perception.

David Claerbout, Breathing Bird (study with single bird), 2021. Collectie De Pont museum, Tilburg. Foto: Peter Cox. © c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2021

So what exactly do you mean by madness?

With madness I refer, with the most banal intentions, to the relationship, or rather the rupture, between your eyes, your perceived world, and your hallucinations. And this is what my works also aim to do, although not in a shocking way. They measure perception and hallucination equally, and gently confront their viewers with a glimpse of madness.