Dutch Democracy, A User Experience – Blog #1: If the Poets Should Have Their Revenge

An English-Language Blog on Governance, the Arts, the State, and Business Unusual Over the 2017 Netherlands’ Elections. Featuring Stefan Themerson (Check the video!)

The current sequence of electoral dramas unfolding either side of the Atlantic spill forth category errors within the liberal-democratic order. Parliamentary and judicial processes stall as the archaic, despotic tendency of the sovereign-state moves to the fore. In Lauren Berlant’s fantastic and heartening USA inauguration-day reflections, she writes of the revived electoral ‘Big Man’ serviced by ‘Big Sovereign Electorate’1. It’s/his way is paved by a rebrand of the nation from liberal-inclusive to defense-of-the-liberal-exclusive. As we know, the third-party of big business rules across both of these configurations. The installation—circa early ‘80s—of market priorities as the leading object of government is what we call ‘neoliberalisation’.

However both models of an inclusive or exclusive state are modeled on the notion of a bounded and autonomous nation-state, and it’s this to which globalization gives the lie. In a sense the momentous elections taking place at present are referenda on the Westphalian state itself. Voters displaced in development want to know, “Is there a state, or isn’t there? Because if there is; we want the tariffs, borders, all of it.”

Where ‘left’ and ‘right’ increasingly fail as explanatory apparatus, ‘metropolitan’ and ‘non-metropolitan’ comes into focus as a governing rubric. In this way, the Brexit vote makes sense as an effort to electorally repatriate metropolitan London to the territorial space of England/the UK. Its voters say to the London élite; “That’s great that you’re so busy in Hong Kong, New York and Dubai; but are you here??”

It’s true that this macro-economic view side-steps the vicious anti-immigrant discourse that has claimed and organized this moment into exclusive nationalism. However, the social/rhetoric arm of the political has long sustained a divorce from the economic in the post-WWII era. The roots lie in the think-tanks of the Reagan and Thatcher years. Here big business sought a narrative by which to convince the working classes that privatization and divestment from social services was desirable. It’s an extraordinary question: how to convince the electoral masses that a transfer of wealth to the CEO class was in their interest.

The result was a media product ‘The New Elite’, based on the idea of a powerful left elite who favored pet minorities to the detriment of the greater nation. An excellent article by Mark Davis charts the Australian chapter of this discourse; its development funded by Western Mining Corp then CEO Hugh Morgan, its movement through Murdoch owned media, and its enormous, long-running electoral success.2 The outcome has been that over the past three decades—in Anglo-European social democracies—the social drama of politics has seen one hand of politics presiding over pitched battles for the entitlements of women, people of color, the disabled etc., while the economic has seen another hand of politics oversee the dramatic sell-off of public assets and withdrawal of support from poor and working communities.

The split is ethical/practical. In the categories of liberal thought, it is the aesthetic that sutures these. What interests us here is how these fissures of liberal-democracy and the urban-rural relation emerge through and are caught up with the category of art and the aesthetic; and from there, of how emergent forms of governance can be tactically contoured through this lens. This is not a project of the valorization of the artist-agent, however. As Victoria Woolf well observed; “heroism is botulism”. These reflections and continuing blog-posts are an effort to stand within a space of contemporary art and—from that view-point—attempt to unravel the operationality of global governance, so as to draft a counter-cartography of the economic and social tactics of the moment. What is clear at the outset is that art stands well within the cross-hairs of the revanchist right.

Take for example the sub-reddit manifesto of the ‘neoreactionaries’—part of the United States ‘alt-right’ championed by President Trump’s key advisor Steve Bannon. Across eleven dot-points the neoreactionaries diagnose their nation-state’s failure to live up to its 17thC European racial and gender priorities, claiming that economic and social failure stems from this cause. In a surprise turn, they deliver their twelfth and final point: “Politics has destroyed aesthetics and made it ugly.”

This online document is extremely similar to the 2017 one-page programme of the poll-leading Dutch “Party for Freedom” (PVV)—also disseminated digitally in the first instance. After a litany of new measures to purge Islam, withdraw from the EU, and a smattering of welfare re-installations; the PVV turns to the arts. Point seven: “No public money for development aid, windmills, art, innovation, broadcasting, etc.” In 2017 the centre-right party (VVD), led by Rutte, has largely permitted the exclusive-nationalist right to set the agenda with statements echoing Wilders’ “love it leave it” stance. In addition, on February 13, VVD policy agenda came to light planning to withdraw 100 million euro from art-education, requiring a drop in students by approximately half.3

This is the story so far. With the election due for March 15th this post marks the start of a blog series written over a one-month stay of residence in Eindhoven, hosted by the Van Abbemuseum and connected to their Becoming More project (18-28 May). Becoming More will mark ten years since the Van Abbemuseum’s high-profile and controversial examination of Dutch Identity Be(com)ing Dutch. The blog will attempt to think the election through the metropolitan/non-metropolitan lens.

The basis of this thinking is the art and research project Frontier Imaginaries. The project is based upon a trans-local method learned from what I call the “Settler Region”—a geographically improper region of the Settler States, including among others Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Israel and formerly South Africa. So far, editions have been held with partners in Brisbane (IMA and QUT Art Museum), as well as Jerusalem (as Jerusalem Show VIII, commissioned by Al Ma’mal Foundation and as part of the 3rd Qalandiya International).

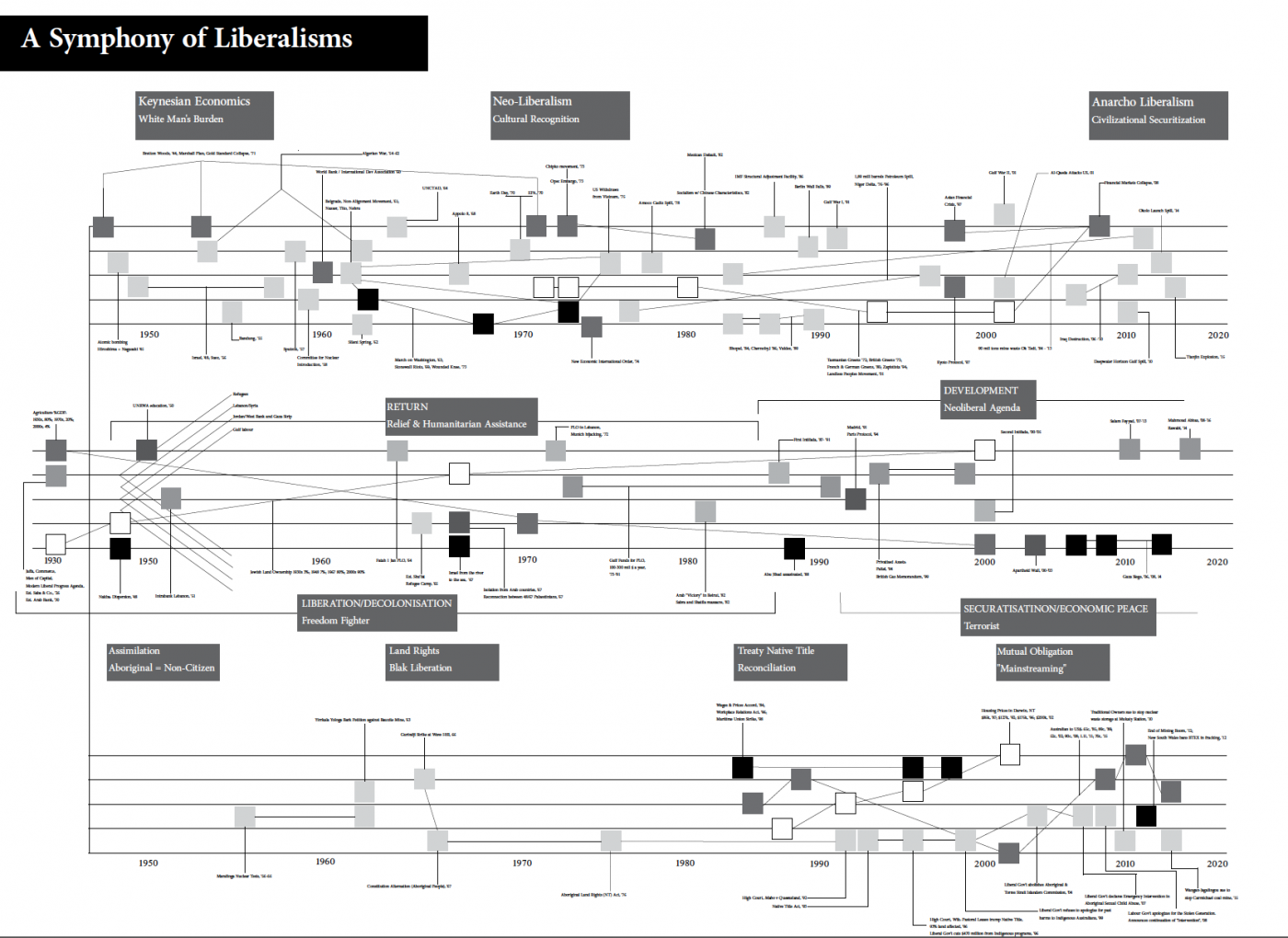

Across each of these steps artists, designers, scholars, archivists and communities have gathered to examine liberal governance as a global phenonmena that can be tactically analysed from local positions. A perspectival shift is called for in this effort, challenging awareness to where and what kind of indicators to tune into. Elizabeth A. Povinelli’s Symphony of Late Liberalisms is a valuable device and plotting practice, listing key events upon global and local stanzas of a musical score. Here the composition of the global melody is also constituted by local scores; modified by regional refrains that disturb its linearity in time, shifting ‘earlyness’ and ‘lateness’. A conversation between Povinelli and the symphony’s Palestinian advisor political-economist Raja Khalidi is published online at Jadaliyya. http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/25681/the-symphony-of-late-liberalism-in-palestine_a-con

In 2016 and 2017 this work will relocate to the Netherlands, bringing its study of the global dramas property and propriety (ownership and behavioral correctness) to the home of ‘Natural Law’, the code underwriting international commodity trade and, as such, the global order. And yet Frontier Imaginaries arrives at a turbulent moment in this long durée. It finds the globality forged and sponsored by European powers such as the Netherlands experiencing a tide of territorial retraction.

This blog, therefore, will reflect upon the election month from the province of Brabant, and in English. The clash here is intended and knowing. English language is one of the most immediate identifiers of the arts immigrant. It signs her Metropolitan attachment through fluency in what Gayatri Spivak has called ‘Global English’. This term emphases the role of language in securing governability; particularly in the exaggerated rhetorical politics of exclusive nationalism. In a sense, the critics of ‘political correctness’ are correct; not that it is acceptable to verbally insult, but that the social-political has been evacuated to a mere practice of being ethical-by-speaking while the economic-political has seen its ethical dimension sidelined becoming merely practical-by-doing.

In concert with forms of media designed exclusively for the social—and not at all for the nuanced discussion of something like economic policy—the results have been disastrous. One might consider the hollow symmetry of this exchange between Rutte (VVD) and Wilders (PVV); apparently the first time Rutter had fired up his Twitter account in five years, and occurring in the absence of the first scheduled debate which was cancelled when both parties refused to participate.

Rutte: “Zero percent (chance) Geert, ZERO percent. It. Is. Not. Going. To. Happen.”

Wilders: “”It’s the voters who are in charge of this country Mark, for a HUNDRED percent. And. Nobody. In. The. Netherlands. Still. Believes. You.”

On this note, perhaps a good point to finish is a little-known television broadcast of the Dutch NOS, now distributed by LUX in the UK, Stefan Themerson and Language. The forty-minute piece was aired in 1976—the year that the final state-owned mine in Limburg was closed shedding 45,000 jobs directly and an estimated 30,000 indirectly; the closures had been an initiative of ‘workers party’ (PvdA) leader Joop den Uyl. 1976 was also the year that the United States officially changed the status of the US Dollar from the Gold Standard, and was three years before the launch of the European Monetary System. In the TV piece, Polish semantic poet Stefan Themerson alleges that the political and religious leaders have committed the crime of stealing the tools of the poet. However, Themersen does not seek the restitution of abused phrases and words. Instead he calls for the semantic restitution of language itself; a process of reinvesting phrases with concreteness and content, re-suturing utterance and mattering.

The final minutes of the programme are dedicated to a traditional Dutch patriotic song—extolling love for the Netherlands—that has been subjected to semantic poetics. Lines that descibing joy experienced upon a sand are translated to the geological co-ordinates, while ‘the Netherlands’ is disambiguated many times over.

The gesture is humorous, but perhaps what played in 1976 as farce should play again in 2017 in the face of tragedy; and as part of a contribution from the arts in a politics to come.

The video can be viewed online here: https://lux.org.uk/work/stefan-themerson-and-language‘

Thanks to Mike Sperlinger for pointing me to Stefan Themerson and Language, and to Gabriëlle Schleijpen for a pointer to the VVD arts education proposed roll-back.

Vivian Ziherl