Care in times of Care

How to make sure that the revaluation of care the COVID-19 crisis seems to bring about will last? Curator Staci Bu Shea have devoted much of their practice to the notion of care within art and culture. Their critical observations inspire ways in which we can continue to take care of care.

“Don’t yuck my yum” is a phrase used by social justice workers, sex educators, and workshop facilitators in attempt to create a safer space with a mixed group. I mentioned this phrase to the student participants of the Dutch Art Institute when discussing initial thoughts on how we’d like to work together across the year in the study COOP “All about my mother” co-tutored by Sepake Angiama and Nina bell F. of Casco Art Institute. Fitting for a collective study on the topic of non-patriarchal institutions and taking up the kitchen as a metaphor, “don’t yuck my yum” directly relates to food, i.e. “do not say my food tastes bad.” There was a revel in the “ohhh” chorus of collective epiphany. It was the first time hearing the phrase for most, but being denigrated or policed about something you enjoy that already takes guts to share is nothing new. According to cultural worker Marcus Borton, a step further would be to “yum another’s yum,” to take joy in another’s joy as a possibility for learning together and as a way to foster mutual respect – “me affirming your existence, desires, and joys doesn’t negate or steal from, nor reveal, my own.”

Compersion is a word that defines this opposite of jealousy, though it is not acknowledged officially in the English language. This kind of expression helps name an unacknowledged behavior in interpersonal communication and invites the listener to reflect on how they share what they “yuck.” A medicinal salve to heal in response to words unintentionally weaponized to hurt, the expression points towards the future. We’re used to the “yum” and “yuck” as part of the evaluation and judgement of what makes up art criticism. Observation and interpretation are sharpened like knives for the chopping block of “how to do things with words.” It is no wonder that the world of art at once promises refuge but can be like any unsafe place.

As someone drawn to the ways in which language gives way to better understandings of experience in order to share and tell stories, I’m interested in how communication can assist in a social planning and make way for new kinds of relationships of care, which is to say new forms of being interested in the needs of others. I refer to planning here in the sense that Stefano Harney and Fred Moten speak of it as a way of living in the undercommons: “in the undercommons of the social reproductive realm, the means, which is to say the planners, are still part of the plan. And the plan is to invent the means in a common experiment…”[1] I also consider care here and everywhere as surplus, an abundance, that when embracing it makes patterns that determine new relations by way of planning for them.

[blockquote]I consider care here and everywhere as surplus, an abundance, that when embracing it makes patterns that determine new relations by way of planning for them

This has altered the way I think about endings. My first instance really dealing with death was working with the late American artist Barbara Hammer (1939-2019), a pioneer in queer art and cinema. For two years Carmel Curtis and I prepared an exhibition of her work to be shown at Leslie Lohman Museum in New York (Oct 2017), the first retrospective of a lesbian artist at the museum to date. Her illness changed my relationship to time and planning, with bouts of urgency, studio visits shortened from fatigue, occasional “scare” visits to the hospital, and deep empathy. The possibility of her death before the opening of her exhibition loomed heavy over our preparations and I often thought about it, unavoidably as one does working closely with an artist who was living dyingly. Challenges in planning with the institution became surreal. Sometimes Barbara would speak in terms of possibly not seeing the show come together, a foreboding that became part of the plan. I leaned on our circadian correspondence. Barbara helped prepare me for her inevitable death, but as much as I became used to the idea, I was not ready. Time slowed. That last year of Barbara’s life featured a feverish production and some exciting collaborations during that time of increased and impending reality. I think about the timing, how working with her when I did with Carmel was only the start of a very exciting period of dying livingly. In the final months of her life, Barbara became increasingly involved in activism for the Right to Die in New York state, to be able to pass with choice and dignity. In many ways, she planned her dying well, with interviews, performances (the one at the Whitney Museum of American Art that Nicole Eisenman referred to as “a reverse funeral”), a home for her archive, a fund for lesbian filmmakers, and so on. Her illness was traversing many years she couldn’t fully plan, but she was ready. She has informed my (and others) current gravitation to death work and my understanding of what it means to live and work with illness and to plan for death. If you “live like you were dying,” communication could either be mean without consequence or careful transmission of your life.

As someone who has devoted much of their practice to thinking about care within art and culture, I’ve grown slightly ambivalent. Do we need another event or text on care without the necessary institutional and organizational change that could really respond to such uncaring times? Its lack of specificity increases the margin of error rather than creating that space as a net to catch and to hold. The evolutionary tinkering of care in the United States and European context led by the most marginalized, namely black queer disabled feminists, has been slowly implemented into institutions but it continues to fall through the cracks. Plus, the kind of care we want can never be made institutional.

If we would like to make the spaces of art a refuge, then the practices of those spaces must ensure that it’s possible. The struggle I contend with is that there are certain aspects to this that should be solid, institutional, so care stops being individual. The problem with care is that it’s too personal. The problem with care is that you often have to be implicated and effected in order to care. The problem with care is having to ask, what if it was your mother, wife, daughter, sister? And other horrifying questions, as if that makes a difference. Now, maybe there is no problem with care itself, but a problem with individualism, or how the other side of intimate touch is violence. A problem of language, a problem of speaking and not being heard, a problem with what is not said, a problem with not having the language and tools for communicating it.

Communication is unarguably one of the most challenging aspects of interpersonal relationships and any collective work. The exciting part of aesthetic and poetic practice is the possibility to infer, to deduce or conclude somethingfrom evidence and reasoning rather than from explicit statements. Or interpret, the act of explaining, reframing, or otherwise showing your own understanding of something. Interpersonal communication, on the other hand, is already performative in its diverse expressions of speech and the cultures that socialize it. I write as a Floridian where “southern hospitality” is a choreography of excessive albeit charming indirect communication. Living here in the Netherlands, the direct communication is efficient yet sometimes insensitive and tactless (no use in telling someone they look tired when you could ask how they’re doing instead).

I would like to put forth tools for communication that require practice as a proposal for preventive care that involves a principle of planning. From institutional to interpersonal study, they are not to be instrumentalized into yet another event on care but are an event of care, and of the perhaps boring variety of organizing and daily, behind the scenes work. This relationship practice takes insistence and flexibility and is only seeds with hopes for germination. I propose preventive care as a form of planning and communication that reproduces the kind of sociality that we need in the face of climate crisis and social injustice, or at the end of times.

I propose preventive care as a form of planning and communication that reproduces the kind of sociality that we need in the face of climate crisis and social injustice, or at the end of times

1) For care to be preventive is not to say that conflict would be avoided. Rather it anticipates the experiences and needs of the other as opposed to reactionary care which is a response to uncaring conditions. Accessibility in movement work and event organizing has been poignantly addressed by many disabled activists, organizers, and artists. Skin, Tooth, and Bone: The Basis of Movement is Our People is a disability justice primer based in the work of Patty Berne and Sins Invalid. Artist Carolyn Lazard’s Accessibility in the Arts: a Promise and a Practice is comprehensive for addressing the multimedia and sensorial qualities of working in the arts.[2] Curator Taraneh Fazeli has organized, written, and presented about care in relation to “access notes” and the way they enact curatorial and institutional care can vary from a gesture of liberal benevolence to a form of radical planning.[3] Institutions can address and share the limits of their built environment to already give a heads up to what one may expect in their plan to visit. Access notes also address race, gender, and class. Likewise, at the start of working with someone, ask them to fill out an access doc[4], which templates are easily locatable online. People’s disabilities might be visible or invisible, and they may or may not identify with them. Some notes in an access doc might include one’s pronouns, their accompaniment of another person of color to white spaces, their emailing and working hours, what they need if they live with anxiety or get tired often, etc. Imagine if there was much more clarity about people’s needs and understanding your own and how we might be able to better anticipate each other and assume less.

2) A trauma-informed and decolonial practice of nonviolent communication should be navigated with consideration of the four i’s of oppression. Oppression is institutionalized, ideological, interpersonal, and internalized. It’s important to see these together as a ringed approach when grappling with one of the i’s to begin to understand how their interplay puts people both at risk for harm and violence as well as can prevent it. When someone has experienced trauma, a life of dealing and healing could be ongoing and non-linear. This could mean that one’s guard is up because situations, people, or information could feel like a threat, which of course makes it harder to open up and be vulnerable. It becomes really important to identify triggers and figure out your needs in order to learn how to communicate them.

3) In The Tyranny of Structurelessness, Jo Freeman includes a high degree of communication as a necessary principle for ensuring democratic process and to be politically effective: “diffusion of information to everyone as frequently as possible. Information is power. Access to information enhances one’s power… The more one knows about how things work and what is happening, the more politically effective one can be.” To this end, this is also integral to trauma-informed nonviolent communication and navigating non-monogamy: provide an abundance of information so people can make fully informed decisions about what might implicate or involve them. Do so ahead of time to allow a moment for response or the ability to be involved in a decision that concerns them. This goes for informing about the length of a symposium presentation to the conditions of one’s freelance work.

I think practicing accountability is one of the most powerful and political tools in resolving conflict and building trust. In other words, own your shit. Own your feelings, triggers, and faults

4) Community organizer and disability activist Mia Mingus has shared material on accountability processes for big and small things: “if you’ve harmed someone (or even just acted really crappy or not in alignment with your values), take the time to truly put the work into being accountable. Changing your behavior is not done overnight. Proactively build support in your life – as in now and everyday, every week, so that you have folks who can support in the hard work of transformation… Accountability is your responsibility.”[5] I think practicing accountability is one of the most powerful and political tools in resolving conflict and building trust. In other words, own your shit. Own your feelings, triggers, and faults. Reparative processes are necessary for healing and growth. Time attending to it is not only time spent but time made for future care.

DIT ARTIKEL IS GEPUBLICEERD IN METROPOLIS M NR 1-2020 SENSORY. STEUN METROPOLIS M, NEEM EEN ABONNEMENT. ALS JE NU EEN JAARABONNEMENT AFSLUIT STUREN WE JE HET NIEUWSTE NUMMER GRATIS OP. MAIL JE NAAM EN ADRES NAAR [email protected]

VOLG METROPOLIS M OP INSTAGRAM: METROPOLISM_MAG

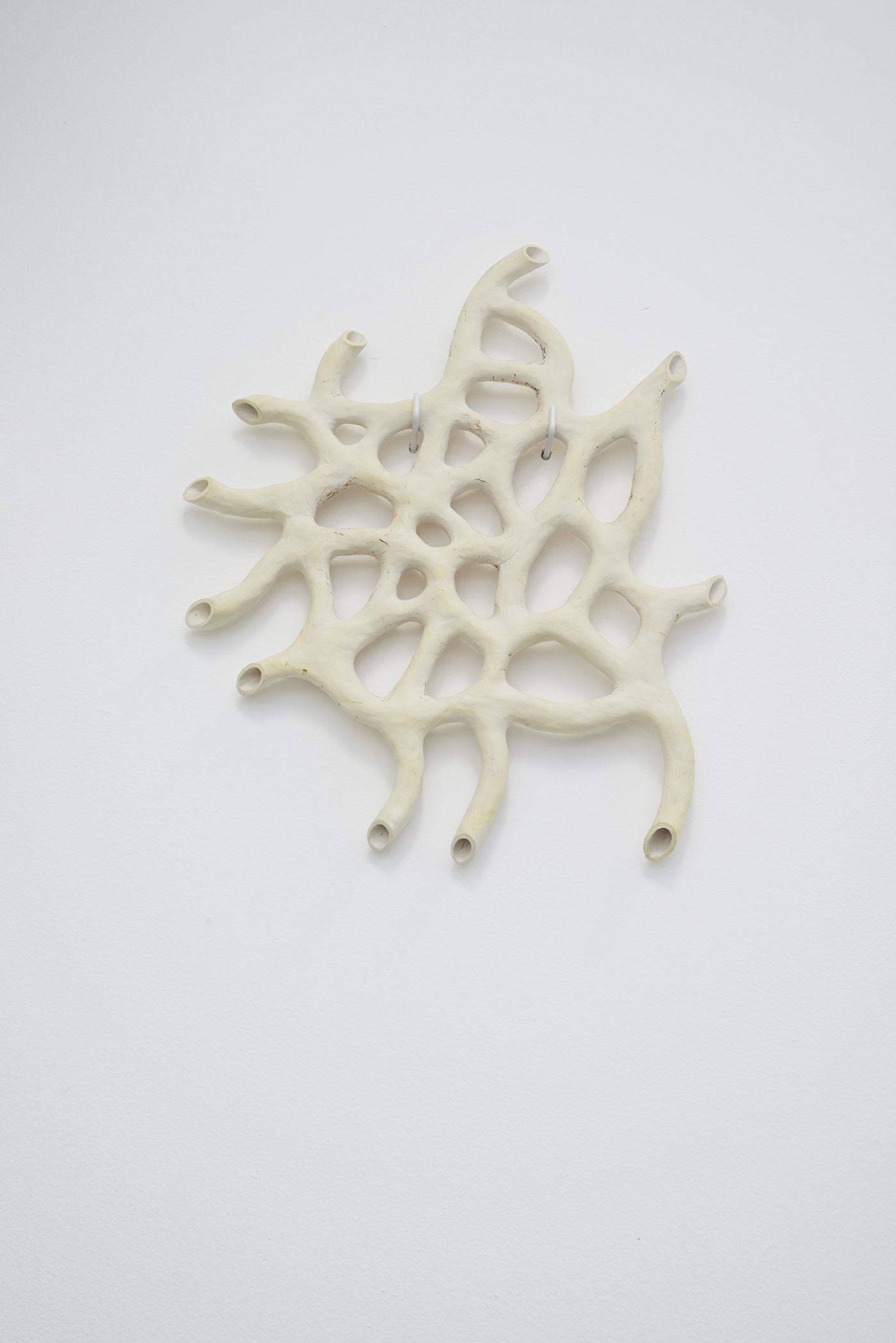

All images are from the show of Molly Palmer at 1646 in The Hague, 2019

[1] Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study, 2013, Minor Compositions, NY, p. 74

[2] Carolyn Lazard, Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and a Practice, 2019, commissioned by Recess, NY http://promiseandpractice.art/

[3] See iterations of Taraneh Fazeli’s curatorial project “Sick Time, Sleepy Time, Crip Time: Against Capitalism’s Temporal Bullying”

[4] Access Docs for Artists, by Leah Clements, Alice Hattrick and Lizzy Rose, 2018 https://www.accessdocsforartists.com/

[5] “Access intimacy: The Missing Link” by Mia Mingus has significantly informed my perspective on care. https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/05/05/access-intimacy-the-missing-link/

Staci Bu Shea