Grammar of Freedom

Opened in the beginning of February in Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, the exhibition Grammar of Freedom / Five Lessons: Works from the Arteast 2000+ Collection shows that life is ironical. Unfortunately.

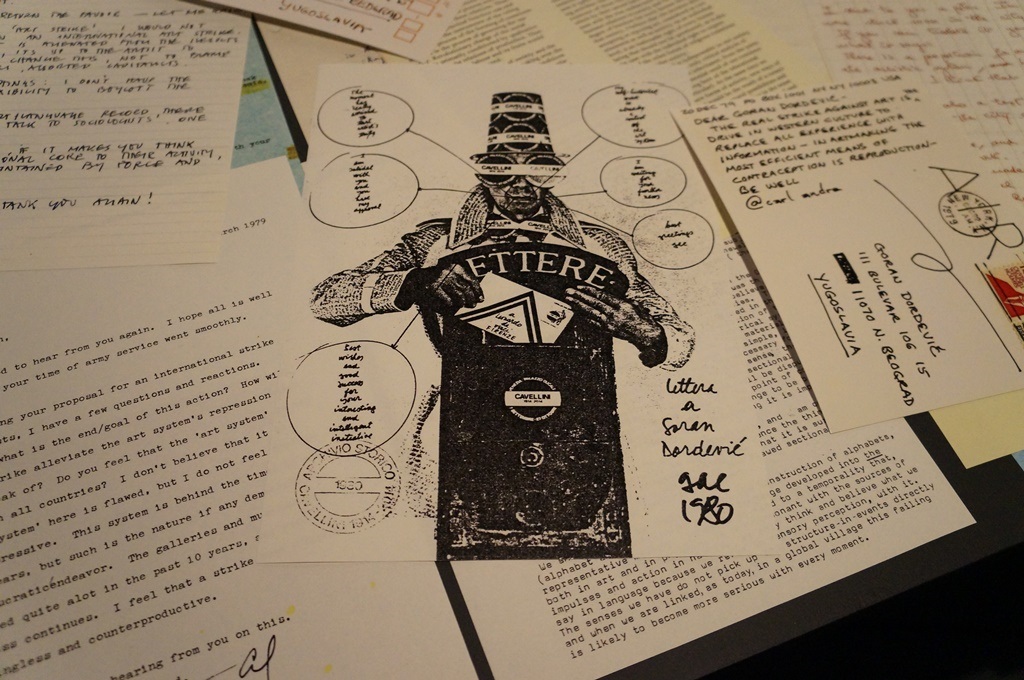

Everyone is present at Garage Museum in Moscow; from Marina Abramovic and Chto Delat, to IRWIN and Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, from Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid, to Dan Perjovschi and Nedko Solakov. It seems that every important Eastern European artist from the late Soviet and Post-Soviet era is invited. The exhibition Grammar of Freedom, curated by the director Zdenka Badovinac and senior curator Bojana Piškur of Moderna Galerija/Museum of Modern Art (Ljubljana), first shown in Ljublana and now in Moscow, and by Snejana Krasteva from Garage, tries to show that Russian art is part of an international movement. No one ever thought about Russian art in that way before since the Russian art scene is so hermetic, not to say completely closed.

Garage’s chief curator Kate Fowle claims that Russia “has never had an exhibition that considers Russian artists in the context of the Eastern Europe scene” (which includes Post-Soviet states of Central Asia and Transcaucasia according to the curators of Grammar of Freedom). This may sound a bit strange but it is not considering the difference between cultural practices in Russia (or the USSR) on the one hand and in Eastern Europe on the other. There was always a symbolic line that was drawn from the Russian side. Not only by theorists, but also by a lot of artists who equally have divided the art context into “ours” and “theirs”. In that sense it is quite strange to see that some institutions in Post-Soviet countries – like Moderna Galerija, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw and even the quite conservative Veletržní Palác in Prague – now neglect that difference and try to discover similarities and a common sociocultural experience in different parts of this former-Socialist region.

The curatorial concept for Grammar of Freedom is based on five principles or “lessons” as they are named: the body as instrument and modus of emancipation; self-organizing institutions as alternatives to conservative museums and authoritarian state; the cooperation between artists over ethnic, religious or political divisions; transgressive practices and tricks for cheating the state or art system; and difficulties of any kind as challenge and motivation that force artists to work. As is shown there were many common languages among the artists, which was also shared with artists abroad.

Ion Grigorescu made video performances in Romania in the 1970s, parallel to what Bruce Nauman did some years earlier in the USA. Yugoslavian artists like Marina Abramovic or Raša Todosijevic adopted the international parole of performance and video art. Dan Perjovschi speaks in the style of the Occupy-movement. Everyone talks and writes in English, the art world’s lingua franca – as it was once ironically underlined by Mladen Stilinovic in his famous “an artist who cannot speak English is no artist”. The Polish art historian Piotr Piotrowski writes “we spoke English with Czechs instead of our own [Polish] language, which is very similar to the Czech language”. Both types of languages were two sides of the same coin. “[T]he West worked as a sort of mirror”, Piotrowski concludes.

There was also another acclaimed mirror at that time in the East, the one as used by Socialist Realism. Paradoxically it didn’t correspond to reality at all. Socialist Realism was the official art movement which was financially and institutionally supported by the government. Socialist Realists claim that they were “showing the truth” but most of the time it was just propaganda combined with elements of kitsch. The art was a complete lie.

In Eastern Europe artists worked on an even more utopian alternative. They simulated Western realities without knowing their exact institutional background. Democratic ideals of artistic freedom or human rights were – mostly unconsciously – perceived in a naïve and sometimes psychedelic manner with a dose of humor (and in some sense it’s still the same). The unofficial East European art scene produced things that could be recognized as a counterculture and protest movement in the West.

Referendum (1972) by the Croatian artist Goran Trbuljak is a work in which he asks passers-by to vote if he is an artist. It could be compared with the polls Hans Haacke did in the early 1970s (Trbuljak even used a ballot box). It was only not as politically serious as in the case of Haacke. The Croatian artist didn’t mean to change the attitude of the“everyman” toward unofficial art, the more any political reality. The artwork was about the artist’s own freedom, he used the situation and the people involved as tools for his own purposes. As was also the case in RG Vietnam (1969) by the Slovenian video artists Nuša & Sre?o Dragan. In the midst of war in Indochina they made a film in which a girl stands, picketing at the imaginary American embassy, with posters picturing different coat hangers.

East European artists tried to determine autonomous zones within the conditions of “real socialism”. So they constructed situations and narratives in which other forms of life became possible (mainly for themselves). It shouldn’t be simply seen as escapism although some of the artists really left their countries and moved to the West. Others lived and worked in hidden circumstances, like the underground. When possible they interacted with a wider audience and definitely didn’t separate themselves from the common (Post-)Soviet social and cultural context. Grigorescu created his own Nicolae Ceaucescu wearing a mask of the last Romanian Communist leader and speaking to him(self).

The video Dialogue with Ceaucescu (1978) is soundless but we can see Ceaucescu sitting side by side with the artist while they read out their conversation mashed up from official media reports. It’s just propagandistic gibberish scrolling down the screen but the artwork is not a simple critique of totalitarian state in a true sense of the word.

As Georg Schöllhammer points out in his text about the artist (Ion Grigorescu: In the Body of the Victim, ed. Marta Dziewanska, Warsaw, 2011) the video poses the distinction between “public” and “private”. Grigorescu used a camera – an object forbidden for private use according to Romanian law at that time. But he went further than just pointing at his privilege as an artist with a camera: even with the use of Orwell-like Newspeak, he talked to Ceaucescu unlike other Romanians. The president is lying and the artist is also lying by speaking his “language”. But this imaginary dialogue let Grigorescu reverse relations: the dictator and his mass-media machine are now instruments, not the artist.

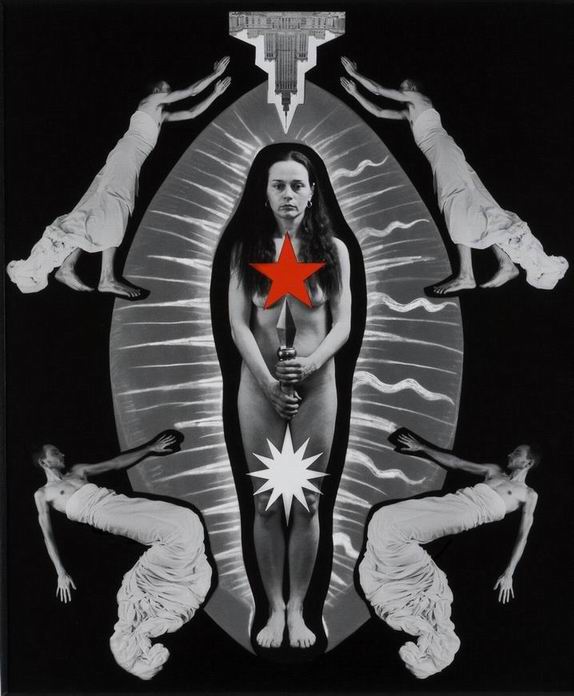

In Self-Portrait with the Palace (1990) the Polish artist Zofia Kulik pictures herself as a goddess or prophetess inside a mandorla with four angelic figures (played by another Polish artist Zbigniew Libera well known for his Lego concentration camp) around her and the “holy spirit” and the inverted Palace of Science and Culture above her head. Since the 1950s this palace and an archetypical piece of Stalinist architecture, a gift of the Soviet Union to Poland, has been standing in the center of Warsaw and always generates debate. Like in the case of Grigorescu, Kulik’s double “blasphemy” against the former Communist cult and revived Catholicism wasn’t made to criticize – the main goal was to place artists in the world, to position herself in the situation of identity crisis after the collapse of the total ideological system. The video installation I am Milica Tomi? (1999) by the Serbian Milica Tomi? also works with that identity problem: repeating “I am Milica Tomi?”, the artist presents herself not as Serbian, Croatian, Muslim, Catholic or Orthodox, but as a wound. In the video, her rotating body is covered by injuries. From the “real socialism” era to nowadays artists moved from irony and individual existence to political engagement in the form of art.

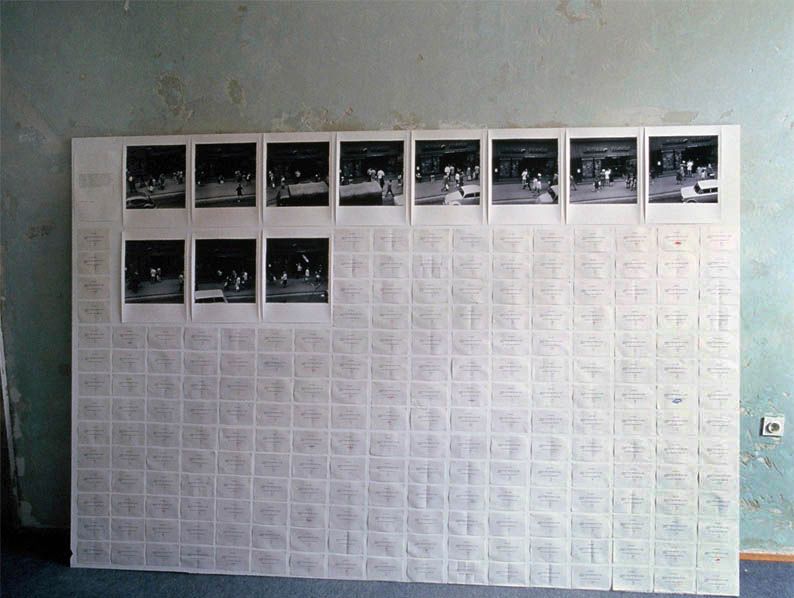

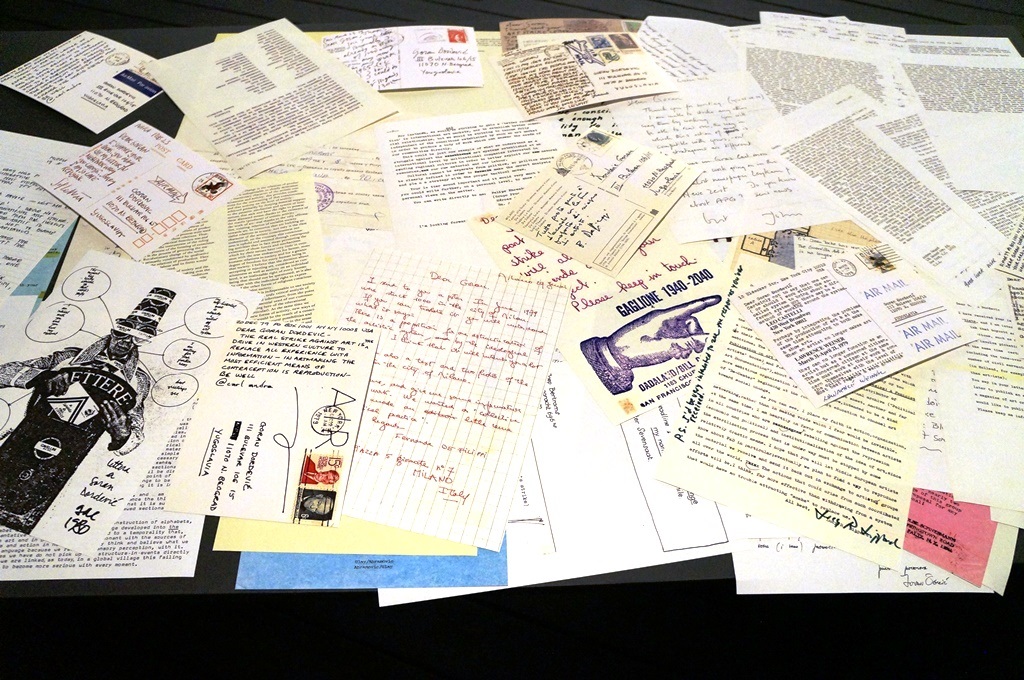

Russian artists on the one hand found other ways of building their zone of freedom. Their practice was more literary based, even if it was a video or installation – famous slogans of the Collective Actions group, words on paintings of Ilya Kabakov and Erik Bulatov etc. Letters to Brother Theo by Yury Albert was taken from Moderna Galerija to the Garage exhibition and was made after the fall of Socialist bloc in the beginning of 1990s. He filled the gap left by the trauma of identification as appeared during the Soviet period, when he ironically confessed “I tried my best to be a real artist, but was only able to make contemporary art. This is a terrible sin”. So Albert has rewritten Van Gogh’s letters to his brother Theo (whose name also means “god”) “only changing the date of their writing and the signature, which I replaced with my own”. It is no accident that these mechanical actions reminds us of rituals: the idea of culture as a religion was widespread among intelligentsia in Socialist countries was appropriated and transgressed from the inside by unofficial artists in a quasi-New Age way.

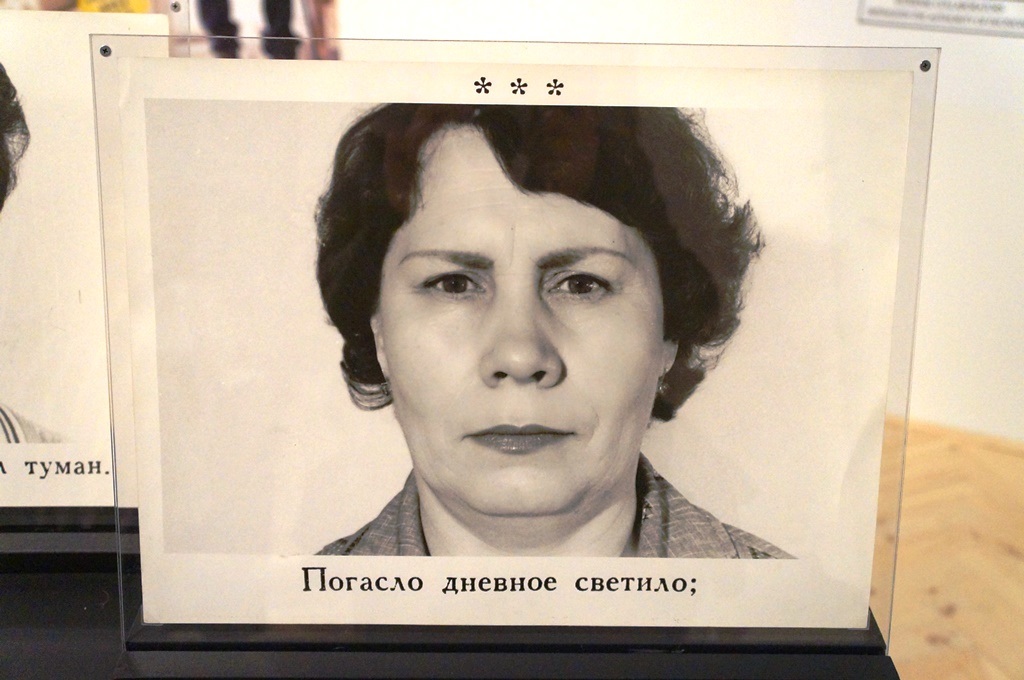

On the other hand in Post-Soviet Russia, as the result of changing social and economic reality, the art community started re-thinking its position and status. There was a shift to artistic researches we might call metaphysical and formalist (that doesn’t decry them at all) like one of the biggest figures of 1980-90s Moscow art scene Vladimir Kupriyanov did with photography towards the same re-politicization in the 2000s. This phenomenon later occured in other East European countries. During the decline of the USSR one of the Moscow telephone exchanges commissioned Kupriyanov to take pictures of its employees for the wall of fame. He then used these portraits for his installation In Memory of Pushkin (1984): every picture is rhymed with a verse of Alexander Pushkin, the famous Russian poet who lived in the nineteenth century. The spectator unwillingly mixes the words and the images of faces – known as the Kuleshov Effect – until he feels a “total decay of notional relations”, as Viktor Misiano supposes.

Thirty years after Kupriyanov made this project, the Chto Delat group and students of the School of Engaged Art (Saint-Petersburg) filmed a piece The Excluded. In a Moment of Danger (2014). In this video, they show an atmosphere of fear and exception. They see no way to escape or just hide from it inside any art narrative. Both artworks are presented at Garage Museum in the nearby halls dedicated to different “lessons” so the audience can see the scale of the shift that occurred in Russian art.

In connection with the exhibition one of the main Russian art critics Anna Tolstova noted a very important fact: Russia still doesn’t have a proper museum of contemporary art and this example of a Slovenian institution should make the people who are in charge of this situation feel ashamed but unfortunately it doesn’t. The discussion about the necessity of a contemporary art museum in Russia is an ongoing story with unexpected twists. A good subject for a following text.

Sergey Guskov is editor of colta.ru

Grammar of Freedom

Garage Museum

6.2 – 19.4.2015

Participants:Marina Abramovi?, Yury Albert, Nika Autor (in collaboration with Marko Bratina, Ciril Oberstar and Jurij Meden (Obzorniška Fronta/Newsreel front), Yury Avvakumov, Jože Barši, Luchezar Boyadjiev, Geta Br?tescu, Alexander Brener and Barbara Schurtz, Olga Chernysheva, Chto Delat group, Lana ?maj?anin, Vuk ?osi? (in collaboration with Alexei Shulgin and Andreas Broeckmann), Goran ?or?evi?, Nuša & Sre?o Dragan, Vadim Fishkin, Gyorgy Galantai, Gorgona, Tomislav Gotovac, Ion Grigorescu, Marina Gržini? & Aina Šmid, Dmitry Gutov, Jusuf Hadžifejzovi?, Tibor Hajas, Ibro Hasanovi?, IRWIN, Sanja Ivekovi?, Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid, Alexander Kosolapov, Jaros?aw Koz?owski, Katarzyna Kozyra, Oleg Kulik, Zofia Kulik, Andreja Kulun?i? (in collaboration with Ibrahim ?uri?, Said Muji?, Osman Pezi?), Vladimir Kupriyanov, KwieKulik, Laibach, Yury Leiderman, Kazimir Malevi?, Yerbossyn Meldibekov, Jan Ml?och, Andrey Monastyrsky, Ivan Moudov, Via Negativa, Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK group), OHO Group, Anatoly Osmolovsky, Marko Pejhan, Dan Perjovschi, Tadej Poga?ar, Darinka Pop-Miti?, Zoran Popovi?, Dmitry Prigov, Franc Purg & Sara Heitlinger, Guia Rigvava, Mykola Rydny, Józef Robakowski, Alexander Roitburd, Arsen Savadov, KAlin Serapionov, Nebojša Šeri?–Šoba, Nedko Solakov, SOSka group, Ilija Šoški?, Petr Štembera, Mladen Stilinovi?, Krassimir Terziev, Raša Todosijevi?, Slaven Tolj, Milica Tomi?, Goran Trbuljak, Josip Vaništa, Sašo Vrabi?, Vadim Zakharov, Dragan Živadinov with Dunja Zupan?i? and Miha Turši?, Konstantin Zvezdochetov.

All images courtesy Garage Museum, Moscow

Sergey Guskov