Cooking Sections, CLIMAVORE: For the Rights of the Soil Not to be Exhausted, 2019, detail, winners of the special prize of the Future Generation Art Prize 2019

New opportunities – Artistic internationalism after the end of the long 1990s – Reflections #16

For Kuba Szreder, today’s political turbulence does not signify that we should move backwards, but rather move on, accelerate, and fulfil the unrealised premises of alter-globalisation. Global contemporary art has to become less privileged in order to be turned into a project of global justice.

What kind of role might contemporary art play in rewinding the project of European integration in the face of the neo-authoritarian turn, in Poland and elsewhere? Instead of unreflectively framing contemporary art as a liberal salve to a nationalist sickness, I would propose a slightly different perspective. Let us consider global artistic circulation – with its biennales, auctions, and corporate museums – as part of the problem. And the solution to an authoritarian challenge must entail the transformation of both global capitalism and global art. I would not abandon the question about the possibility of progressive connectivism on an international scale, as it is more pressing than ever. The collapse of neoliberal globalisation, a project that cracks in front of our own eyes under the weight of its own contradictions and unresolved tensions, created a structural vacuum filled by new nationalisms, authoritarianism, and resurgent fascism. This poses a challenge to rethink artistic internationalism, not by simply reinstating the failed premises of global circulation of artistic commodities, but rather considering artistic internationalism as a contributor to an unfinished project, of another, more just and equal globalisation, a creativity and access for all and not just the privileged few. In other words, I propose here to rethink the project of artistic internationalism after the end of “the long 1990s”.

The very concept of the long 1990s requires an explanation. Recently, together with Jesus Carrillo, a theoretician and curator from Madrid, I discussed the period of the long 1990s a lot, as we questioned the old forms of artistic circulation and think of new possibilities for making and maintaining progressive connections in the context of L’Internationale, a coalition of European museums. The concept of the long 1990s is fashioned after the idea of “the long twentieth century”, proposed by Giovanni Arrighi in his compelling history of the global capitalist system. According to him, the long twentieth century began in the Italian city states of the Early Renaissance period, where merchant classes invented bank scripts (early fiat money) and the first insurances. They reinvested merchant capital as industrial capital, established proto-manufactures, managed long international logistical networks and erected the fundaments for the global division of capital and labour, between capitalist centres and subservient peripheries.

[blockquote]The solution to an authoritarian challenge must entail the transformation of both global capitalism and global art

Anyway, just as the long twentieth century did not begin in 1900, the long 1990s did not begin on the 1st of January of 1990. It did not even begin in 1989, as liberal apologists of the end-of-history projected. Possibly, they begun with the raise of neoliberalism, somewhere in the late 1970s and early 1980s, with the co-optation of 1960s rebellions by the new spirit of capitalism, the crushing of trade unions in the UK by Margaret Thatcher, the financialisation of global economy after the end of the Breton Woods agreement, with the Solidarity movement in Poland and the war in Afghanistan spelling an end to the Soviet Empire, with the reforms of Deng Xiaoping in China. In the artistic universe the long 1990s possibly started in 1973, when Ethel and Robert Scull auctioned the works of Robert Raushenberg and Andy Warhol among a plethora of other artworks, marking the beginning of the speculative art market. Or maybe it was ten years after, when in the 1980s in the very same New York, a “SoHo effect” came into being in result of what Sharin Zukin called the “artistic mode of production”, when art became a force of gentrification, co-opted as part of the FIRE sector (finance, insurance, real-estate). Or maybe it begun with the exhibition Magiciens de la Terre, in 1989, a beacon of new, global art world, that integrated artistic peripheries into the international flow of signs and commodities.

When did the long 1990s end? Definitely not on the 31st of December of 1999. Possibly not even on the 11th September of 2001, and not really in the Summer of 2008, when the financial crisis hit the fan. I would concur that it was in the midst of the 2010s when the neoliberal project of globalisation suffered a drawback, if not a final death blow at the hands of Brexiteers, Donald Trump, Matteo Salvini, Tayyip Erdoğan, Vladimir Putin, Viktor Orban, Jarosław Kaczyński and co. Their ascent heralded the end of neoliberal hegemony, funded on a double promise of economic growth and democratisation.

But what did the long 1990s entail? For me personally, growing up in Poland, the 1990s was a period of becoming-European, tourist visas to the EU (one had to leave every three months), catching temporary jobs in Western capitals (not very legal), the first Erasmus scholarships (preferred to live in Amsterdam squats), but also a period of permanent crises, privatisation of public goods, resurgence of class hierarchies as new fortunes contrasted with new poverty, an endless tightening of the belt, of sacrifices demanded in the name of becoming-European. It was also a period when a new-old Cold War was waged between critical art and conservative society, with contemporary art venerating its own image as more modern, global, cosmopolitan, enlightened, tolerant. Even if a battle was lost, and an artist here and there ended up censored or even prosecuted, the progress of history inevitably lead in the direction of Europe (considered as being more rich, modern, tolerant, cosmopolitan, etcetera), and the effort of catching up would be ultimately justified. Every contemporary art institution built, every connection made, every cross-border project realised, every gallery entering the international art market, every stellar artistic career made abroad, were considered to be beacons of normality, of becoming-Western, veneers of a new, gilded age of happy-crappy globalisation.

[blockquote]Even if a battle was lost, and an artist here and there ended up censored or even prosecuted, the progress of history inevitably lead in the direction of Europe (considered as being more rich, modern, tolerant, cosmopolitan, etcetera), and the effort of catching up would be ultimately justified

Imagine the shock when it all crumbled in the mid-2010s, not only with the neo-authoritarian turn. This could be considered to be the most striking symptom of underlying processes that signified the end of a period of neoliberal globalisation, which just twenty years before feted itself as the end of history. Thinking about it from the Central European perspective, it has a bit of Central European irony in it, yet again trying to catch up with a train of modernisation, and when one finally, after a long chase, finds a seat in the economy class, just catching one’s breath, the whole project ends up in a miserable train wreck. At the very least, we are all in this together. And this end-of-the-end-of-history has tremendous implications for the (art) world(s) as we know it, not only in Poland, but everywhere.

In Poland, just as elsewhere, the globalist project collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions and unfulfilled promises. The architects of Polish transformation and the agents of artistic globalisation alike believed firmly that the very integration of Poland into the international flow will bring with itself not only prosperity, but also a new age of social liberalisation. People seriously invested in Richard Florida’s mumbo-jumbo about creative class, they believed that creativity brings capital, technology merges with talent and tolerance (sic!), and that transforming a former factory into a museum will mark the beginning of the era of prosperity and emancipation. Well, happy days, long gone. Technology brought Facebook bubbles, and turned the public sphere into a multitude of global villages, as prone to manipulation as any other insulated community. The myth of creative meritocracy was dispelled by the reality of privileged access, as the metropolitan corridors are structured by the hierarchies of class, race, and gender.

Currently, the really rich in Poland do what other really rich people everywhere do: they invest in the education of their offspring, send them to Oxbridge or the Ivy League. And the very same people who are being sent to elitist schools at the age of six, after growing up pretend that they owe everything to their hard work and talent. Seriously? Still, the liberal dream of tolerant openness prevents naming this for what it is: a good old class system, where winning the ticket at the natal lottery determines one’s future more than anything else. Instead of facing the hard truth, better to muse about open access on the flight to the Maldives in the midst of a wet winter, as the snow melts quicker than it falls, all due to the broken climate that is not able to sustain the dreams of endless growth. In this sense, Poland is well integrated into Europe, even though such lifestyle is only reserved for the metropolitan elites. As a result of the neoliberal transformation Poland ended up being one of the most unequal countries on the continent.

Rising inequality, rather than democratisation and tolerance, has been one of the direct outcomes of the long 1990s. And this inequality is juxtaposed with the division between centres and peripheries. In Poland, just as everywhere else, larger cities are integrated in metropolitan corridors, sucking up human beings, resources, and energy from their industrial and agricultural hinterlands, as the subservient links in logistical chains suffer from underinvestment, poorer infrastructures, limited access, and brain drain. It is an inherent feature of the most recent wave of globalisation, identified for what it is already twenty years ago by thinkers like Zygmunt Bauman and Saskia Sassen, who punctured the dreams of creative class and creative cities and unearthed the fundamental divisions brought in by globalisation.

Beyond any doubt, the long 1990s witnessed an emergence of the global artistic network, dotted with biennales, fairs, franchises, auction houses, foundations, glittering with newsletters, landmark exhibitions, record prices, seminal projects. However, as Gregory Sholette pointed out a decade ago, this brave new world of enterprise culture was and still is underpinned by the chthonic realm of artistic dark matter, a residue of unrecognised, yet socially necessary, artistic labour. The global artistic circulation was shaped after the global flow of capital, reproducing the very fundamental divisions of globalisation. The throngs of unrecognised artists are similar to any other “loser of globalisation” as they are excluded from the public realm. People who do not fit into the brave new spirit of interconnected capitalism have to become invisible, so as not to spoil the global sport.

Finally coming back to the initial question: what about art after the end of the long 1990s? As Sholette suggests, the privileged sections of the global art circulation currently run around as naked as the emperor in the old tale, no longer able to project their own self-image of a spearhead of modernisation: more cosmopolitan, enlightened, benevolent than everyone else. The global art, when turned into a commodity, is at best a tourist attraction and at worst a display of unearned privilege, senseless accumulation, and unchecked power. One can only be thankful that the hegemony of speculative art market fades alongside the epoch that brought it into being. Much more interesting stuff is happening at grass-roots level, amongst the institutions, movements, and individuals that re-imagine the artistic globalisation as a postcolonial, alter-globalist project.

The recent report “Art, Alter-Globalism, and the Neo-Authoritarian Turn”, published in the latest issue of the journal Field, proves that hard times bring new opportunities. Poring through dozens of reports from all continents, one can see that everywhere, not only in Poland, new-old hybrid subjectivities emerge, of artists-researchers, curators-activists, intellectuals-producers, people who are not as easily subdued by the false pretences of global circulation, more tactical in their search of opportunities, more careful in forging alliances, and more loyal to their allies. An example at hand is the civic coalition of Antifascist Year in Poland, a platform gathering over two hundred public art institutions, collectives, and individuals, both from metropolitan centres and smaller towns, who will work on a programme of antifascist exhibitions, projects, and manifestations in 2019 and 2020. As part of this project, a L’Internationale summit will be called by the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw in October of 2019. Connectivity at its finest. In the process, artistic institutions refashion themselves as civic, constituent or socially useful museums or art centres, not hotbeds of gentrification or dance halls of accumulation, but safe spaces for queer activists, discussion platforms for antifascists, research centres for feminists, partners of local communities and social movements. Individual artists, collectives, movements and constituent museums, are not defaulting back into the cult of localised or nativist, and neither are they the heralds of unbridled, global capitalism. On the contrary, they are harbingers of more just and less hierarchical globalisation.

[blockquote]One can only be thankful that the hegemony of speculative art market fades alongside the epoch that brought it into being. Much more interesting stuff is happening at grass-roots level

It is not a time to move backwards, but rather to move on, to accelerate, and fulfil the unrealised premises of alter-globalisation so that the global contemporary art, instead of being a privilege limited to metropolitan corridors and non-places for global elites, is turned into a project of global justice, actually functioning and not just offering illusionary access. The globalists become alter-globalists as, rephrasing Louis Aragon and Walter Benjamin, “traitors of their own metropolitan class of origin”. As such, they forge a link in the chain of equivalences for new, socialist globalisation, one that challenges the hierarchies of class, race, gender, geography, and tackles climate justice. Such an alter-globalist project is a counter-force to the neo-authoritarian, nativist reaction to globalisation, filling the structural void left after the end-of-the-end-of-history. It is a time for a new Internationale, for finishing the unfinished project of alter-globality. Art has its historical role to play, time will tell which one it will be.

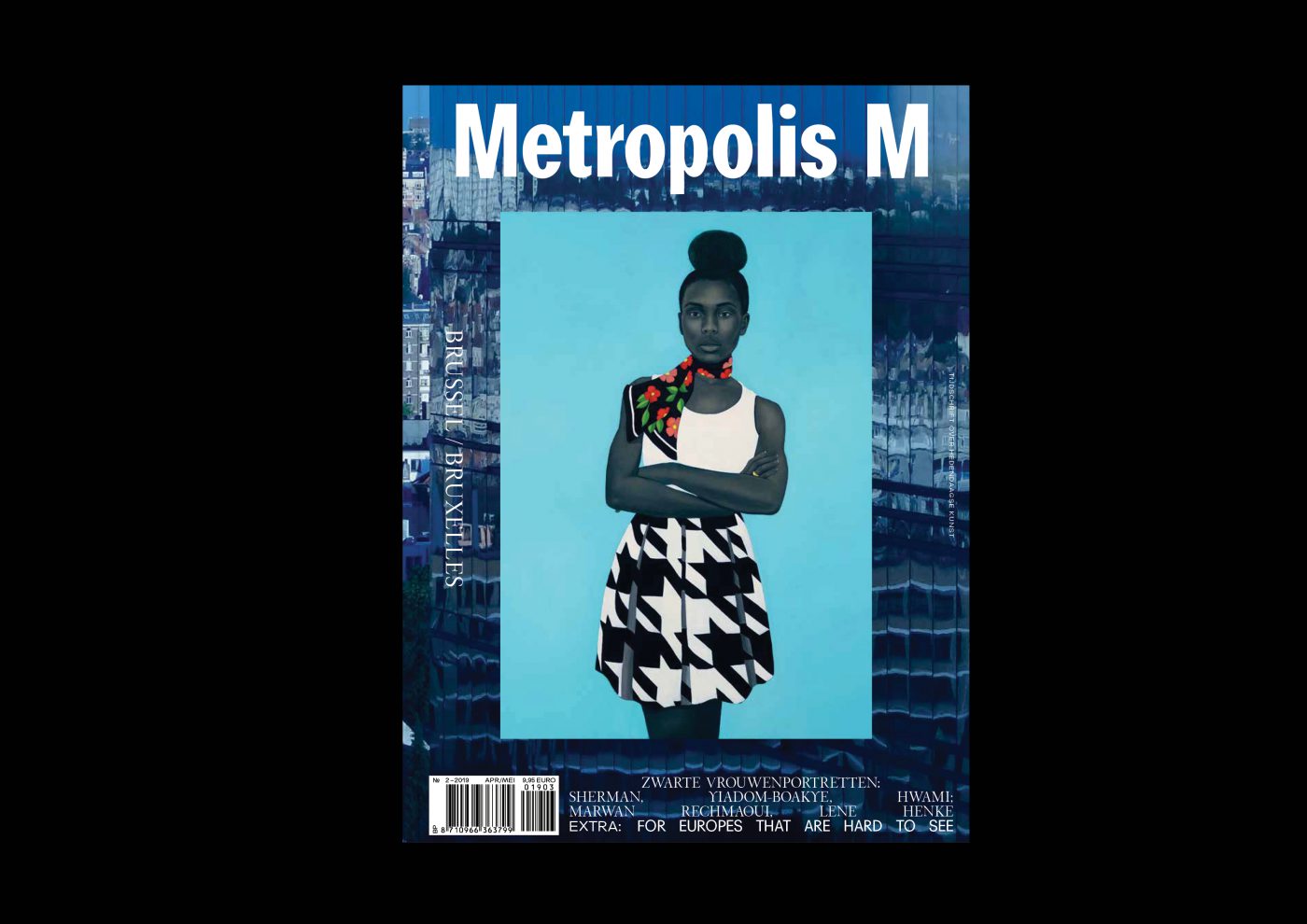

DIT ARTIKEL IS IN EEN NEDERLANDSE VERTALING GEPUBLICEERD IN Metropolis M Nr3-2019 Brussel/Bruxelles – For Europes That Are Hard to See – Zwarte Vrouwenportretten.METROPOLIS M KRIJGT GEEN SUBSIDIE. STEUN METROPOLIS M, NEEM EEN ABONNEMENT. ALS JE NU EEN JAARABONNEMENT AFSLUIT, STUREN WE JE HET NIEUWSTE NUMMER GRATIS OP. MAIL JE NAAM EN ADRES NAAR [email protected]

Kuba Szreder

is a researcher, lecturer and independent curator