Canan Senol ‘I am an activist, feminist artist’

Beginning this month I met the Turkish artist Canan Senol in Istanbul. (I visited Istanbul as part of the 2010 Orientation trip organized by among others the Mondriaan Foundation). One of the topics of our conversation was a recent video-animation of Canan Senol, entitledExemplary that is now being shown at the exhibition ACT V: POWER ALONE , (part of the year-long program Morality), in Witte de With in Rotterdam.

Comparing the politician to the artist, I think Canan Senols work provides a nuance and openness to the subject that is interesting.

Working on the interview with Canan Senol two weeks later coincided with the debate around Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s new book Nomad and I realized that the two things had everything to do with each other. Both women are storytellers, and both tell the story of a woman in a period of transition, moving from a rural area to a modern city and society, resulting in the clash of modern secular values with the moral conservatives of religion, in this case Islam. In the book Nomad the protagonist is Ayaan Hirschi Ali herself, who recounts her personal journey from the pre-modern mindset of nomadic Somali society to a modern Western one. In the video-animation Exemplary the protagonist is Fadike, a Kurdish woman who moved from a small village at the countryside of Turkey to Istanbul. Ayaan Hirschi Ali’s book results in the searing indictment of the cult of ‘multiculturalism’ and ‘diversity’ in the Netherlands, which according to her disables Muslims in the West from making the necessary ‘mental transition’ towards western values of freedom and democracy. Hirschi Ali’s story provides interesting and political daring viewpoints, but I have a problem with her one-sided point of view. Comparing the politician to the artist, I think Canan Senols work provides a nuance, openness and complexity to the subject that is interesting.

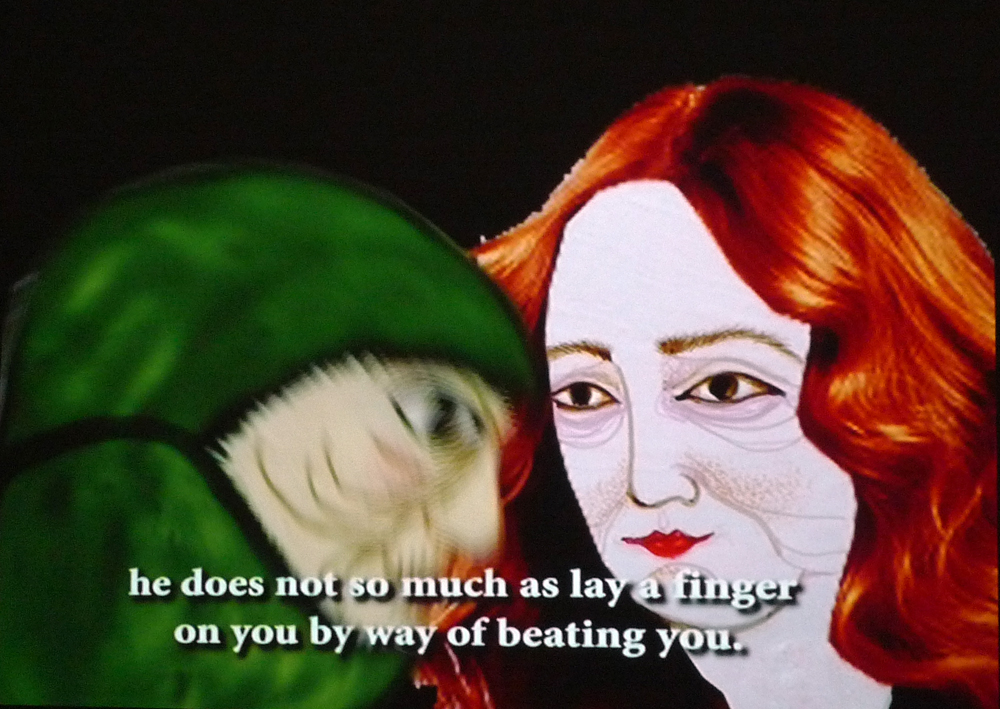

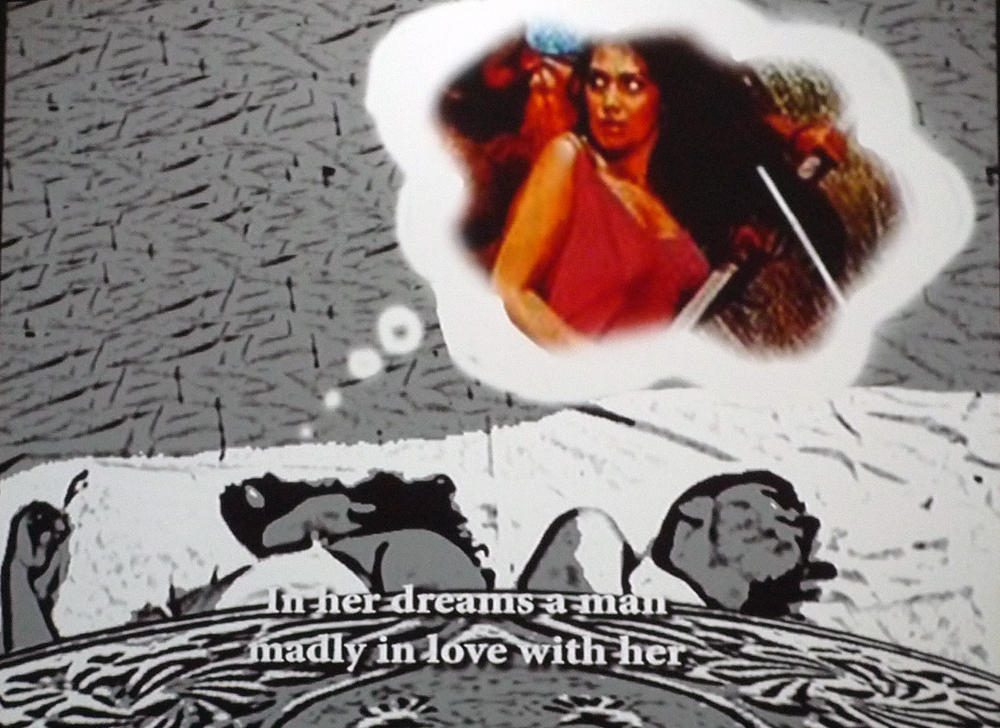

The video-animation Exemplary tells the sad story of the beautiful Fadike, who has no other choice but to obey to the traditional, moral values of her ‘wicked’ mother. She ends up in a forced marriage and her husband sexually abuses their son. The only way Fadike is able to respond is to resign in her faith. Can you tell something about the background of this work?

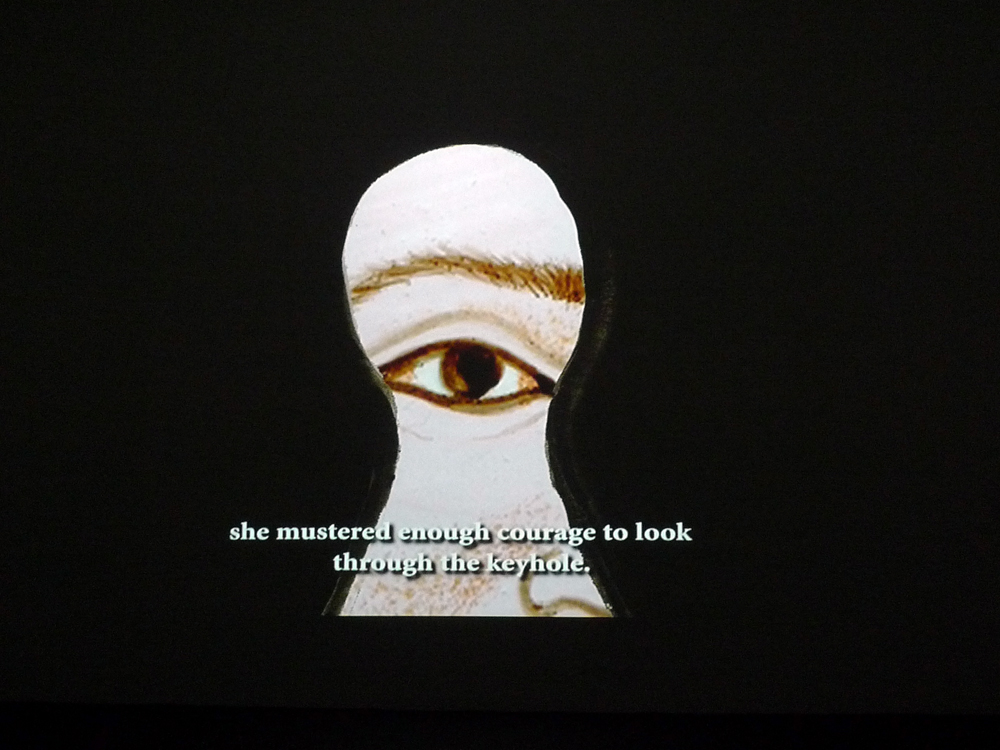

‘In my work I’m concentrated on the very local and personal life of people, because I believe that the personal is the political. But my work also relates to geopolitics. Michel Foucault and his book on surveillance and punishment in which he develops the notion of present society in which everybody seeks to restrain themselves and live up to unstated expectations inspire me. Foucault uses the structure of the panoptic building, in the sense of a circular prison with a room in the middle for the guard, as a symbol of the disciplinary and normalizing society. The inmates feel under constant surveillance and naturally behave as such. I use the Panopticon as a symbol to show how religion, the family and the state disciplines the individual’s private life. I’m concerned with cases in which the societal discipline cause assaults on the individual’s integrity, as is the case in the story of Fadike.’

Do you think the Panopticon as a model is applicable to a certain part of society?

‘No, I think it holds a certain kind of truth to society at large. It’s a complex process in which religion, society and governmental powers are intertwined. It tries to take control over the body and mind and uses the body of the women as a political tool. I see it as a universal model.’

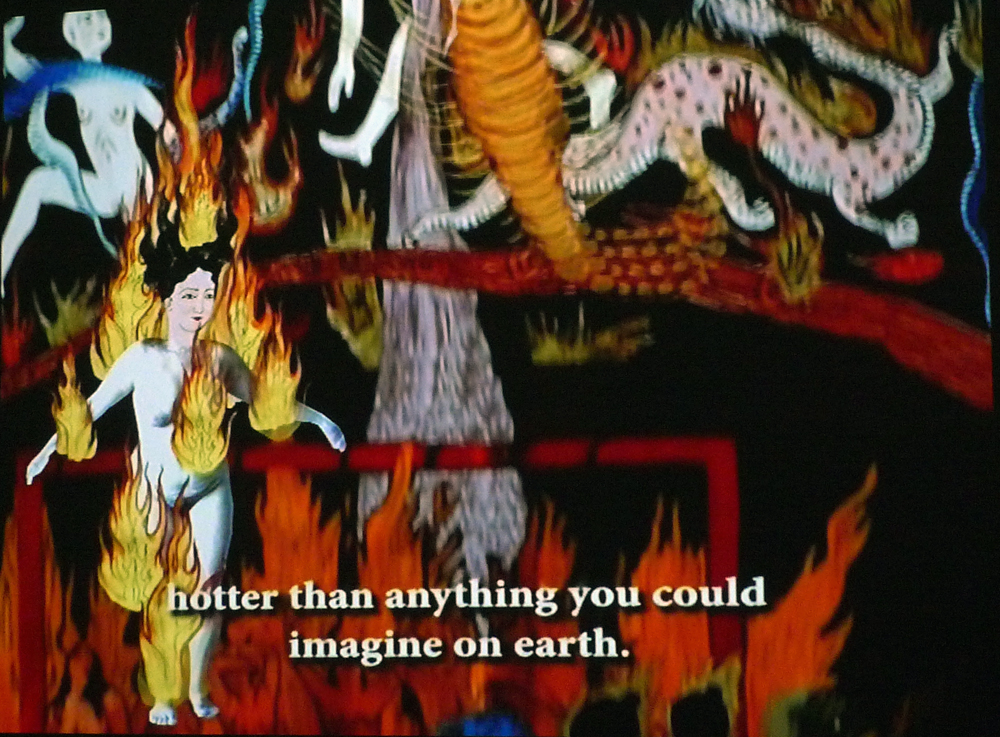

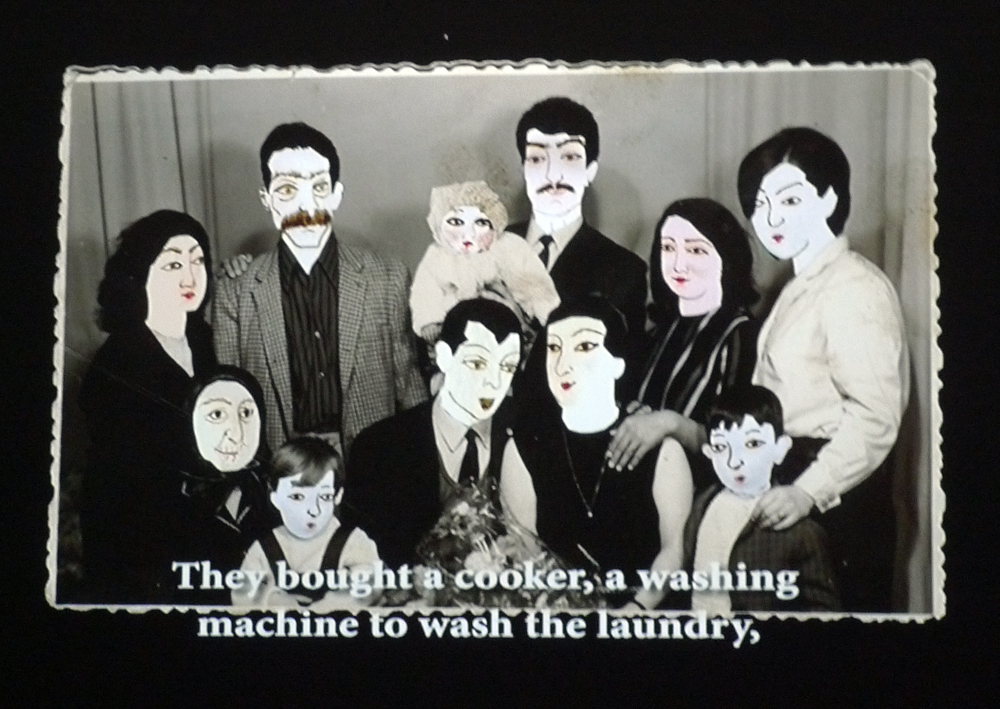

The animation is build up with drawings that resemble classical Ottoman miniature, combined with collaged fragments and photo material. The sadness of the story of Fadike contrasts with the aesthetic language of the forms that are used, was that a deliberate choice?

‘Thinking about how Turkey became modern and why we lost the connection to the history of our culture, gave me another vision on art. I was educated within the educational system of the Bauhaus-model in Istanbul. I had no idea of the art history of the Ottoman painting or Islamic art. When the republic of Turkey was created this brought about a rupture between the old and new culture. Because of the change in language and alphabet, we were cut off of an important part of our cultural heritage. Nowadays people are not interested in this part of art history anymore, but I think it is important. I used old Ottoman miniatures as an inspiration for the story I wrote about Fadike, as well as for the drawings that I made. These drawings are interspersed with photo-material and then animated in the form of a video.’

‘Thinking about how Turkey became modern and why we lost the connection to the history of our culture, gave me another vision on art.’

The narrative style of Exemplary is akin to One Thousand and One Nights. Why did you choose to go back to this way of storytelling?

‘You could say that during the process the miniature is reworked with new media, but at the end it more or less comes back to its original form. To me this resembles the history of Turkey. The history is exoticized not only by the West but also as part of the Republican culture. Ottoman miniatures are seen with an oriental mind: lustful, they arouse curiosity, it’s like a fantasy, it’s a look, but it’s not about the real things. I want to make them real again. The narrative style of One Thousand and One Nights has a double layer; it’s always about a story in a story. I have copied that literally but also in the way form and content work together. The personal story of Fadike is not only a story about immigration, it’s also a story about the modernization in Turkey and how this influenced the life of women, and the form is also criticizing the way we deal with our past in defining the Ottoman period as “The Other”.’

How does your work relate to the present Turkish society?

‘Actually I’m not Turkish but Kurdish, but I usually call myself an artist from Turkey, because being an Kurdish artist is problematic. When you look at my artworks you can see how I feel as a women in Turkey. It’s a very delicate subject. If you look at Islamic culture you can find all kinds of negative, but also positive aspects about women. So I really want to stress the fact that’s not about Islam per se, but how the system is working. For me it’s not important which party is in the parliament and whether they call themselves conservative or democratic. If you look at how many women were in the parliament since the beginning of the republic; very few. In Turkey modernism and democracy went hand in hand. There was a modern image of the Turkish women created: but their mind didn’t change. This is what I want to criticize; the body should not be used as a political tool. In other words: women have rights but are not able to use it because society hasn’t changed. The current government couldn’t even change the forbidden rules of the veiled women. In official places like the court or school it is still forbidden for women to go without a veil. The power that is behind this, that is what holds my interest.’

Ingrid Commandeur