The Anti-Encyclopaedia From Poetic Disorder to Political Anti-Order (and back again)

Over the years many artists have been criticizing the idea of universal knowledge. Christel Vesters describes the history of the Anti-Encyclopaedia and gives some recent examples.

Encyclopaedia, also spelled encyclopedia: reference work containing information on all branches of knowledge or that treats a particular branch of knowledge in a comprehensive manner.

[Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, accessed March 10, 2013]

In his introduction to The Order of Things (1966), the philosopher Michel Foucault quotes a passage from ‘a certain Chinese encyclopedia’. The fragment describes how ‘the animals can be divided into: a) belonging to the Emperor b) embalmed, c) tame, d) suckling pigs, e) sirens, f) fabulous, g) stray dogs, h) included in the present classification, i) frenzied, j) innumerable, k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, l) et cetera, m) having just broken the water pitcher, n) that from a long way off look like flies.’1

When he read the passage, Foucault said that he burst out laughing. This arrangement, in which domesticated animals and mythical creatures exist side by side, ‘shattered all the familiar landmarks of my thought – our thought – the thought that bears the stamp of our age and our geography…’ The bizarre classification system transcends what is logically thinkable and imaginable, confronting readers with the limitations of their own thinking. At the same time, says Foucault, there is an exotic charm to this heterotopic and heteroclitic classification of things: disorder as a poetic argument, as it were.

The paradoxical listing of animals to which Foucault refers is from an essay by the Argentinian poet and writer Jorge Luis Borges. Borges, who cited it in El idioma analítico John Wilkins, published in 1942, claimed that the fragment stemmed from an ancient Chinese encyclopaedia that bears the equally enchanting name, Emporio celestial de conocimientos bene volos (Celestial Realm of Good-hearted Knowledge), and attributes its discovery to the German lawyer Franz W. Kuhn. To date, the actual existence of either the Chinese encyclopaedia or the surreal taxonomy remain unconfirmed, but both their alleged discoverer, Franz Kuhn, and the protagonist in Borges’ essay, the Englishman John Wilkins, certainly did.2 3

John Wilkins lived in the 17th century. In addition to being a clergyman and natural philosopher, he was a co-founder of the Royal Society (for Improving Natural Knowledge). In 1668, he published An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language, in which he explained his system for a universal, philosophical language. This new language would make it possible to construct and express ‘any possible idea or thing in the universe’ in an unambiguous way. Like other Enlightenment thinkers, Wilkins aspired to a lingua franca that would enable and promote the exchange of scientific knowledge. His utopian project was an outstanding example of the enlightenment ideal of a universal system in which all human (read: objective and rational) knowledge could be conveniently and accessibly organized.

In his essay, Borges reflects on Wilkins’ universal language, comparing its system of classification with that of ‘a certain Chinese encyclopaedia’. As Borges often merged fiction and pseudo-scholarly references in his writing, it is highly likely that the paradoxical list of animals was born of the imagination of the writer.4 Borges’ main purpose for introducing the fictional system of classification seems to have been to introduce a counterpoint and alternative to Wilkins’ analytical organization of the world. By doing so, he indirectly questions the arbitrary – and culturally determined – nature of any system, scientific or otherwise, Western or non-Western, which claims to offer a universal categorization of all things in this world.5

Fictional Encyclopaedia as Anti-Encyclopaedia

Borges’ essay and Foucault’s critical analysis of the history of our thinking tell us that encyclopaedias are more than just catalogues of knowledge. They not only reveal how, ‘in a certain age and geography’, people interpret and give meaning to the world around them, but they also reveal the prevailing ideas about the (true) nature of knowledge, which knowledge was/is considered important enough to be collected and disseminated in the encyclopaedic canon, and the beliefs that underpin these decisions.

The history of art and literature includes many examples of fictional encyclopaedias and other fictional reference works (lexicons, dictionaries, indexes, etc.) that ridicule and undermine efforts to establish any systematic classification of all human knowledge. They sometimes poke fun at the utopian notion of omniscience and the desire for total knowledge (as in Borges’ essay or Gustave Flaubert’s posthumously published 1881 novel, Bouvard et Pécuchet, which Flaubert himself dubbed an encyclopaedia of human stupidity). Other examples speculate about the true nature of knowledge, for example by indexing an absurd ‘field of knowledge’, such practical jokes, prehistoric life or conspiracy theories. Finally, there are also fictional encyclopaedias that map a world that can only exist in the imagination and where everyday life follows completely different rules. One of the most evocative examples of this is perhaps the Codex Serafini, published in 1983 by the Italian architect Luigi Serafini.6

Although these examples toy with the official status and authority of the encyclopaedia and the knowledge that it represents, the idea of a fictional encyclopaedia becomes all the more interesting when writers or artists take over the structure and modus operandi of the encyclopedia and apply it to a radical political agenda. The enchanting appeal of this poetic disorder becomes a ragged-edged, dystopian anti-order. In these so-called anti-encyclopaedias, the criticism is often of a more social or ideological nature, addressing such questions as who decides what knowledge is, and on what authority. Whose encyclopaedia is it, anyway? And whose worldview does it represent?

Da Costa Encyclopédique

One of art history’s more illustrious – and obscure – examples of such an anti-encyclopaedia is Le Da Costa Encyclopédique. The Complete Da Costa was presumably a project by Acéphale, a secret society of left-wing intellectuals and artists centred around Georges Bataille. The identity of the authors has never officially been confirmed – the participants swore anonymity – but from various memoirs, one can conclude that at least Georges Bataille, André Breton, Robert Lebel and Michel Leiris contributed. Marcel Duchamps was reportedly responsible for the encyclopaedia’s design, as well as for the famous ‘License to Live’ illustration and the article on chess/echecs.

The first – and only – printing of Le Da Costa Encyclopédique appeared unannounced in the autumn of 1947 in selected bookstores near Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Designed to look like a conventional encyclopaedia, the ‘Fascicule VII, Volume II’ (Instalment VII, Volume 2), as its cover sheet announced, contained a series of articles on various subjects, including economics, education and the church, with and without illustrations. Remarkably, the text on the first page began not only mid-sentence, but also in the middle of a word: ‘…festations that are unexplained in the context of modern science’. This incompleteness certainly threw any number of potential readers off guard. The abrupt onset, the contents of the first sentence and the subject of the next article – Echecs, which means both ‘chess’ and ‘failures’ – all seem to hint at the (dis)illusion of total knowledge, which was of course the aim of the modern encyclopaedia. But there is a deeper checkmate or failure to which the Da Costa also alludes, which is the failure of utopian and positivistic faith in science as the driving force behind human progress.

The Da Costa’s rarity and the lack of information about its creators have undoubtedly contributed to the myths that the publication has generated, but the controversial nature of its contents certainly enhanced its cult status. In the most direct manner, and not without humour, the authors bluntly criticize social institutions, including state, church and education. Da Costa’s definition of ‘school’, for example, is, ‘an institution where people are taught that it is prohibited to use both hands, and where the left (hand) has no right, even if it is more adroit than the right.’

The articles in the Da Costa differ in style. Some are literary or pseudo-scientific, while others read more like broadsheets. Despite its conventional appearance, the Da Costa broke with all encyclopaedic conventions. It is fragmentary and incomplete (after the letter E, no further instalments appeared), the texts are very personal and subjective, and their veracity (scientific authority) is questionable. But it is precisely here, in this combination of conventional form and controversial content, that the political and subversive agency of the Da Costa lies. Disorder is instrumentalized as anti-order.

Art as Alternative Knowledge – The World Explained

In the current debate on art and knowledge, artistic research and the discursive turn, the idea of art as a different form of knowledge often functions as a critique. Art as an alternative system of knowledge offers resistance to the prevailing idea that all knowledge production should serve a particular purpose or need, or should strive for ‘value’ according to the dictates of the neoliberal knowledge economy or ‘cognitive capitalism’. The much-cited discourse says that art can provide a platform for ‘the other’, the unknown, and thus create room for new, speculative forms of knowledge. But what in fact is this other, ‘holistic and non-logocentric’ knowledge?

A recent example of an encyclopaedia-cum-art project, which speculates about another form of knowledge, is The World Explained, a project by the Mexican artist Erick Beltrán. For this project, initiated in Sao Paolo in the fall of 2008 and recently completed at the Tropical Museum in Amsterdam, the artist interviewed people in the streets and in the museum. On the basis of such questions as ‘What is power? How do you explain the cold? Can we avoid disappointment? Can the blind see colour?’, Beltrán collected what he calls personal theories: forms of everyday, unspecialized knowledge. The questions were formulated in such a way that it was almost impossible to come up with instantly logical and rational answers. People were sometimes confronted with combinations of questions, but in any case, they were challenged to call on their imaginations and speculate on possible explanations. For Beltrán, this informal, unspecialized knowledge is as important as formal, learned knowledge, and it is in fact these ‘personal theories’ that largely determine our social reality. In Beltrán’s intricate epistemological theory, clusters of personal theories provide us with systems of thought and ultimately evolve into cultural patterns that we consider as ’true’.

Beltrán collated the personal theories he collected from the interviews into texts, which he then published in The World Explained: Micro Historical Encyclopaedia. He deliberately selected the encyclopaedia format, modelling the cover after the Cyclopaedia, [a] Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, published in 1728 by the Englishman Ephraim Chambers, which is considered the first modern encyclopedia.7 But Beltran’s Encyclopaedia is anything but an official canon of objective facts and absolute knowledge. The articles bear such titles as ‘Blind / Colour / Backstage’, ‘Tickling / Evolution / Glamour’, which refer to the configurations of questions, as well as the genesis of possible knowledge: Knowledge is not static or universal, but is continuously changing and subject to personal impressions and experiences. By copying the design of the first modern encyclopedia, Beltrán explicitly positions his project in the context of the Enlightenment ‘project’. Beltrán’s Encyclopaedia, in which he brings informal and non-specialized knowledge to the foreground, should not so much be understood as an anti-encyclopedia, but as a döppelganger.

As in the Chambers Cyclopaedia and the later Encyclopaedia edited by Diderot and D’Alembert, all the items in Beltran’s Encyclopaedia are illustrated with explanatory diagrams and drawings. In topological studies of encyclopaedias, much has been written about the relationship between text and image and the ways in which knowledge is organized. In both traditional encyclopaedias and Beltran’s interpretation, the combination of text and image provides a certain aesthetic and ‘enchanting attraction’, which simultaneously opens a parallel, imaginary space where the imagination has ascendancy over reason.

Parallel Encyclopaedia

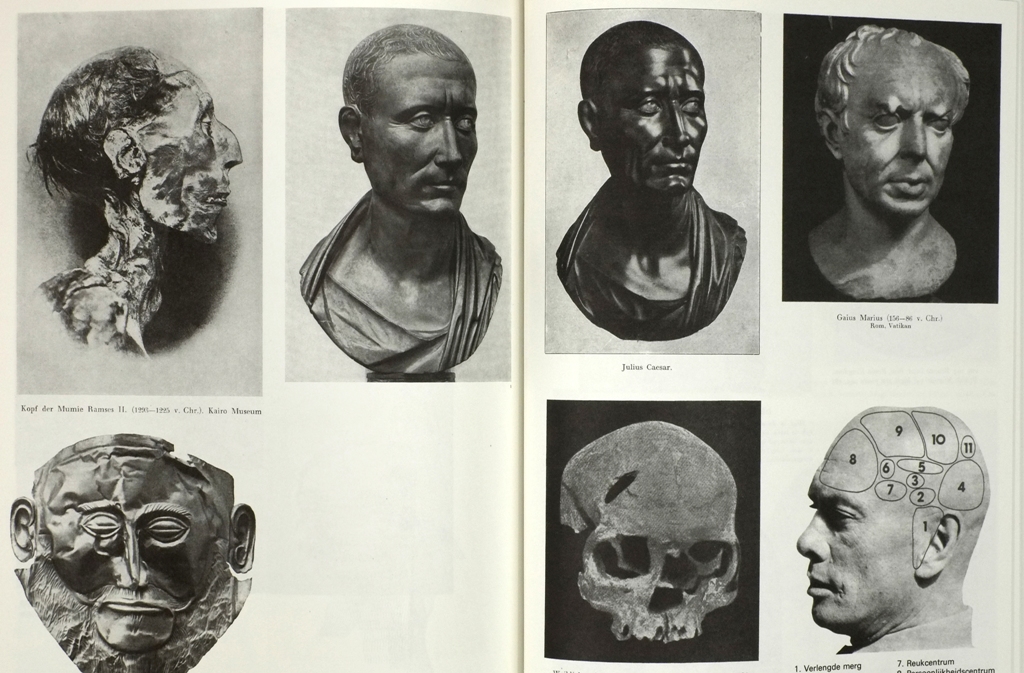

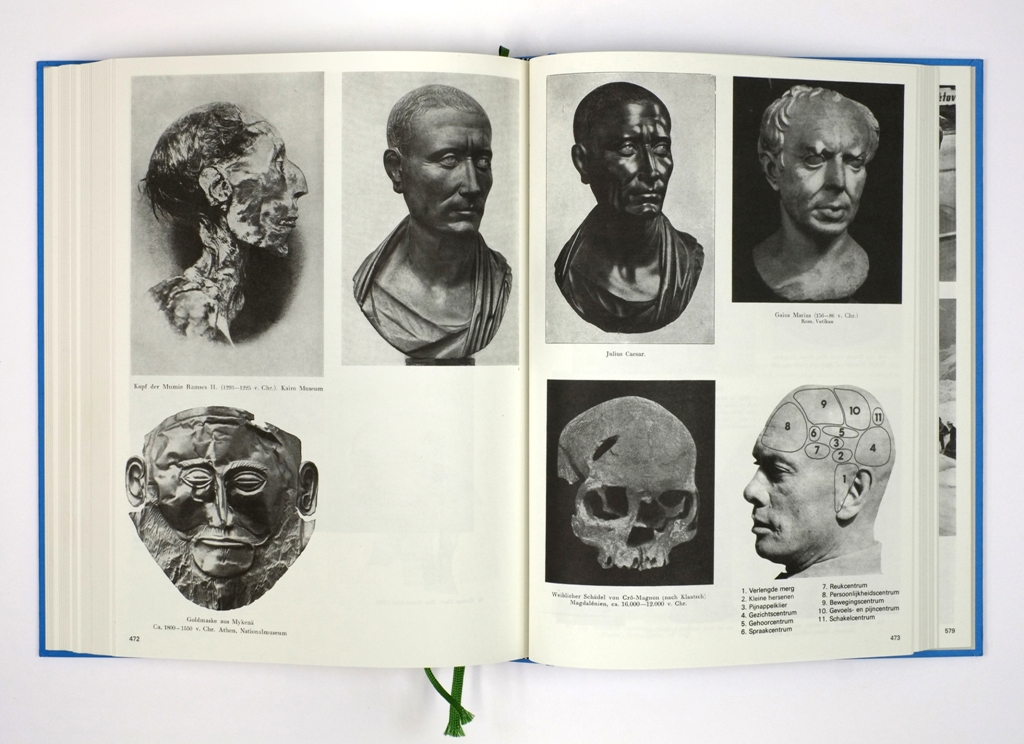

One artist who understands the power of images as carriers of encyclopaedic knowlegde and has followed it through in its most radical form is the Swiss artist, Batia Suter. In her 2007 book and exhibition project, Parallel Encyclopaedia, a window onto the world in which we live unfolds through a myriad of found images. From images with geometric and circular motifs and pictures of round shapes (like planets or blow-fish), we seamlessly continue on to images of oil tankers, landscapes, bridges, various sorts of upholstery, typewriters and insects, to finally arrive at the final section, which contains representations of humankind in all its guises.

All the images that Suter has brought together in her Parallel Encyclopaedia are taken from other books and publications. This recycling and appropriation of ‘found knowledge’ is a strategy used by many artists (think of the numerous archive-based works as outcomes of artistic research projects), but in Suter’s case, the focus is primarily on the associative connections between the different images and the various narratives and patterns that emerge in the space of a single page, and in between, within the space of the encyclopaedia as a whole. Back in his day, Diderot had already spoken of the idea of a dialogue between text and image, and the possible metonymies that could result from the juxtaposition of topics, or of texts and images, which would normally never appear alongside one another. He, however, considered this a shortcoming of his encyclopaedic project. In Suter’s work, in contrast, the heraclitic arrangement of visual information is at the core of the project’s poetic power, inviting viewers and readers to a ‘multilateral’ reading or browsing of information.

In this respect, Suter’s Parallel Encyclopaedia recalls the ‘exotic charm’ of the cabinet of curiosities, the encyclopaedic predecessor of the museum, in which the owner – driven by curiosity – collected mostly exotic and strange objects, brought together with no particular or logical order. Like the cabinet of curiosities, Suter’s Parallel Encyclopaedia embodies a space in which lack of order creates a space for wonder, for not knowing, for another form of knowledge, or in short, the (non)order of the imagination.

Christel Vesters is an art historian, art critic and curator.

This text has been translated from Dutch by the author and edited by Mari Shields.

THIS TEXT HAS BEEN PUBLISHED IN DUTCH IN METROPOLIS M No 3-2013

1 Michel Foucault, The Order of Things, 1966, Editions Gallimard, Paris, p. xv

2 John Wilkins (1 January 1614-19 November 1672) was an English clergyman, natural philosopher and author, founder of the Invisible College, co-founder of the Royal Society and Bishop of Chester from 1668 until his death. Wilkins was one of the few people to have headed a college at both Oxford and Cambridge Universities. He was a polymath, was instrumental in reducing political tension in Interregnum Oxford, founding the Royal Society on non-partisan lines, and in efforts to reach out to religious nonconformists. He was a founder of a new natural theology compatible with the thinking of the time. He is best known for An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language, in which he proposed a universal language for scientists and philosophers and a decimal system of measure not unlike the modern metric system. [Wikipedia, accessed March 19, 2013]

3 Franz W. Kuhn – not to be confused with the American scientist and philosopher of science Thomas S. Kuhn – lived in Germany between 1884 and 1961, where he worked as a lawyer and translator. After he studied Law at the University of Leipzig and Berlin, he as send to Peking as a translator to the German delegation in China. After the First World War, Kuhn began to translate classic Chinese literature into German. Eventually he ran into conflict with the Nazi authorities, who considered his works to be harmful. After the end of World War II, Kuhn’s work began to be more widely known and appreciated. Kuhn is best know for his translation of Der Traum der rotten Kammer (1932). [wikipedia, accessed March 19, 2013)

4

Borges’ oeuvre features many more fictive encyclopedias: The encyclopedia of Tlön, for instance, from the novel Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis, Tertius which allows people to discard of all their worldly books, cultural arte facts and languages; El Libro de los seres imaginarios contains 120 descriptions of fabulous animals originally found in folklore tales and literature. The Greek artist Christiana Soulou, whose work is included in the 55th edition of the Venice Biennale, titled Il Palazzo Enciclopedico, recently created a series of drawings in which she animates the animals mentioned in Borges’

5

From the 18th Century onwards most modern encyclopaedias included a preliminary discourse on the nature of knowledge it contained, its origins – and thereby its authority – and the systemic relationship between the different areas of knowledge. A well-known representation of the logical order of the presupposed knowledge system is the so called tree of knowledge in the Encyclopédie van Diderot en d’Alembert, which shows how knowledge can be classified according to a certrain hierarchy and genealogy. Subsequent knowledge systems were represented as labyrints, maps, networks or rhizomes

6 A small selection: the German author Novalis worked on his Encyclopedia of the Romantic Movement, titled getiteld Algemeine Brouillon (1798/99) in which he explained his ideas of a holistic science; Ambrose Bierce published his Devil’s Dictionary (1911), in George Perec’s Life A Users Manual (1978) the protegonist Cinon worked on the big dictionary of forgotten words; in 2002 Herve Le Tellier publiceshed his Encyclopedie Inutilis and Koen Brams recently published his Encyclopedia of Fictional Artists and also the catalogue which accompanied Manifesta 9 The Deep of the Modern, titled Subcyclopedia. adopted an encyclopedic format.

7 Ephraim Chambers (1680 – 15 mei 1740) was an English writer and encyclopedist who is best known for his Cyclopaedia, (or Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences). Chambers’ Cyclopaedia was the inspiration for the famous Encyclopaedie by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert.

Christel Vesters