‘Identity is a notoriously contested concept’

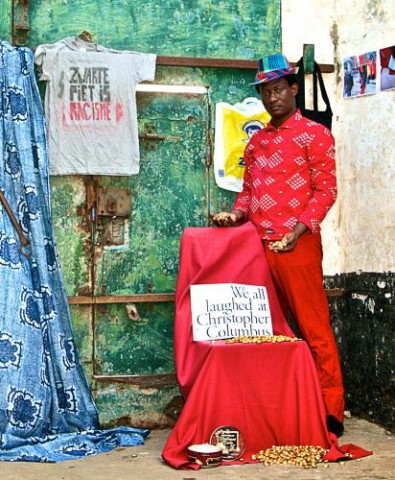

Bernard Akoi Jackson, artist from Ghana, is invited by the Stedelijk Museum for a residency in Amsterdam. He talks about his live in Africa and Amsterdam. ‘I want to believe that the Stedelijk indeed is opening up to the vast world(s) now, after so many years of physical and methodological closure.’

Could you briefly sketch your background? Where and when were you born, where does (most of) your family live and what cultural or maybe religious education have your received at home and at school? What kind of artistic education or other (university) education have your received? For what reason and when did you leave for Europe for the first time? What is your motivation for the residency you are currently doing?

What reason, then, do you think would have brought me to Europe?

[answer Bernard Akoi-Jackson]My background is indeed quite nuanced. Being Ghanaian is already an exercise in a sort of ‘bricolage’ hybrid identity. To be historically aware that Africa as a continent has been the site of globalization(s) long before the concept came into mundane use in the West, is a position many tend not to adequately acknowledge. Also, this postcolonial entity that was eventually named ‘Ghana’ by Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of the nation state, was modeled upon the western conception of territory. Having even emerged as a result of the whims of Von Bismarck and his allies in 1884-1885, already presents paradoxes.

So having been born in Accra, the capital of Ghana in 1979, my cultural and, if we may, religious space had already received a lot of rupture. I always quip that in Ghana, my dad hails from the Northern Region of the country, my mom from the Volta Region in the South; they met in Kumasi (capital of the Asante Region), close to the centre and I was born in Accra the capital and heart of the Ga-Dangme culture. This sense of multicultural mobility has been a constant feature of my life, but that of all my family too. So you’ll find us all scattered, not only over the territorial specificity of Ghana but across worlds all over. I spent close to ten years also in Botswana, since my Dad was working there. So my siblings and I have this expanded space of awareness and pan-Africanist, indeed ‘global’ perception.

My art education happened in the context of a university; Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, located in Kumasi, has birthed a whole list of formidable artists in the world, and it is this history that I participate in. What reason, then, do you think would have brought me to Europe? It would have been, as a matter of course, to further expand my reach and touch more spaces with my hybridity, and simultaneously, to somehow be touched too. It is a reciprocal gesture, this back-and-forth movement. It actually becomes cyclical.

So when I first came to Berlin in 2004, it was to attend the Mobileacademy (a brilliant concept that is still being run by Hannah Hurtzig and her multicultural, multidisciplinary team of experts and non-experts). It was a great experience. Having been an archetypal navigator of ‘the cross-roads’, I remember having made a performance at Checkpoint Charlie in the centre of Berlin.

My current residency with the Stedelijk Museum is, once more, an opportunity to engage in this discourse of globalization in the context of a huge museum dedicated to Modernist Art. What potential for instance, has a post-post-modernist, ‘globally’ oriented art program like the “Global Collaborations” project has for future societies?

I am very certain we can begin to enumerate the several instances of potential and we’ll keep counting many more years from now. It is interesting to note too that this residency is closely linked to the education department of the museum. I am collaborating with this dynamic group of youth called the Blikopeners and another organization, Diversion. This is a recipe for multicultural awareness, growth and maturity.

In what ways has working/doing a residency abroad, and being in between different cultures, affected you personally? Would you rather say it made you develop a concrete sense of belonging or did it rather uproot you? If one or the other applies, could you describe this sensation further?

It will be thus unfortunate if interest in me and my work were only rooted in a parochial thirst for an exoticized “Other,” which I would then read as a form of repressed and eroticized anthropological voyeurism

[answer Bernard Akoi-Jackson]I guess you’d have already grasped a sense of my several experiences with spaces and places. You could say in a way I have been riding Foucault’s “heterotopias” for quite long. Because of this, my outlook has always been positive towards intercultural exchanges. Mine is a strategy of negotiations rather than belonging. I identify with Adorno’s saying that “The highest form of morality is not to feel at home in one’s own home (…)”. I even expand it further to suggest that it is immoral to feel at home just anywhere or everywhere.

I believe by constantly reviewing and revising our concepts of ‘the home’ or ‘the domicile’ we keep reminding ourselves of life’s dynamism. This gives us some agency in all our dealings. I will not describe my experiences in the European space as uprooting. When audience is being sought with my work, I read it as the yearning of other spaces to engage with my intellect. To illustrate it more clearly, I’m thinking of Koyo Kouoh, when she suggests that such exchanges “build grounds of respect and recognition”. She comments, in her response to Senam Okudzeto in an ‘Open Dialogue’ (on Decolonising African Art, Transnational Contexts and Contradiction) in an SMBA publication (Project 1975), that “It is not your western passport or colour of your skin that makes you interesting or attractive, but rather the quality of ideas coming out of your mind” (2014:125)*.

It will be thus unfortunate if interest in me and my work were only rooted in a parochial thirst for an exoticized “Other,” which I would then read as a form of repressed and eroticized anthropological voyeurism. I want to believe that the Stedelijk is by this gesture indeed opening up to the vast world(s) now, after so many years of physical and methodological closure. These new interactions should birth, what I seek, new negotiations.

What are the major differences and similarities between the local, African cultural and artistic community and the local, Dutch you could tease out for the way they have affected you? Which aspects can you identify with, with which you cannot?

Isn’t it curious that fourteen years into the 21st Century, we are still constantly confronted by this ‘spectre’ of a “local African cultural and artistic community” in comparison to a “local Dutch” one? Do you appreciate that by even suggesting “Africa,” you imply an entire continent, against a specific country in western Europe? With all that we know about the world and geography, I don’t think a reductionist view of Africa as a country is permissible any longer. The continent is too complex a being for that. It will therefore be quite unfair, on the part of the Netherlands, if we’re to pitch this multilayered landscape of visual culture in “Africa” against a “Dutch locality” that is largely homogeneous yet, albeit gradually becoming ‘tolerant’ of other cultures and orientations.

If however, we’re to consider the specific art worlds in the local contexts of Accra and Amsterdam, then we can claim that there is quite more vibrancy on the latter scene than the former. But this is said in the knowledge that the ‘artscape’ in Accra is not mediated or state funded in any way and that most efforts are privately initiated and supported and are largely artist-led – what in the Dutch context might be considered ‘alternative.’

In the Amsterdam experience, there exist parallel ‘canonical’ and ‘alternative’ systems. So we can assume that in Amsterdam, artists have a lot more opportunities for making and showing work. So how might the artists in the Dutch context feel, if they were thrown into a financially austere situation as pertains to the Ghanaian scene? But this has been our reality for so long, yet we remain dedicated to our work.

A few years ago, when Western governments started introducing cuts in funding for the arts, some artists and art institutions were thrown into panic. The hilarious contrary is what might happen in Ghana. I want to imagine what panic there would be in Accra, if the state suddenly decided to fund the arts. So in this sense, both art scenes have a lot to learn from each other. How to deal with austerity on the one hand, and how to deal with plenty on the other.

What are other, basic influences that have a lasting effect on you and your life?

Humanity will always have a lasting effect on my life and work.

If so, in what ways has your connection to Europe, and in specific, Amsterdam in the Netherlands, concretely affected your artistic work?

I guess I work because of and in spite of the spaces I’ve experienced. Since my practice often emanates as a reaction to or commentary upon the space I’m inhabiting at a particular time, Amsterdam will concretely affect work that I create here as much as Accra will or any other place.

But since I’m also dedicated to my cause(s), any one reading my work will notice a constant engagement with criticality and a yearning towards ambiguity or indeterminacy. My critique will always be at global capitalism and how it seeks to exclude the majority of humanity, whilst fictitiously riding on the nomenclature of “globalization”. I seek for democracy also, but not that strain that courts anarchy. Mine is for a democracy that can truly be humane.

If your work does in certain terms evolve around the notion of identity ?itself, in what ways do you address and re-work/consider it?

Identity is a notoriously contested concept. And so gives to a lot of engagement and iteration. My work has considered this concept in several ways. I have dealt, for instance, with notions of identity construction, stereotyping and bureaucracy, as pertains to movement and space politics. But I always look at these issues through a filter of wit and humour. I like them because they become potent decoys to dealing with hardcore iniquities in society.

- see more in Bouwhuis J.& Winking, K.(Eds)(2014), ”Project 1975: Contemporary Art and the Postcolonial Unconscious.” Black Dog Publishing. London UK

Svea Jürgenson

is a set designer and prop stylist currently based in Zurich