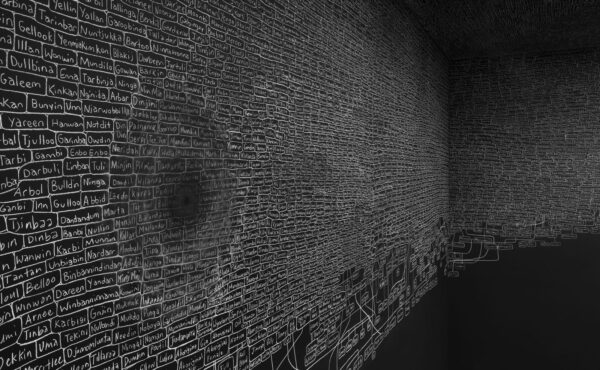

‘Demo II’, 2018/2019, performance and installation by Rosa Sijben in collaboration with Tracian Meikle (Amsterdam Black Women collective)

‘The depth of my work consists in finding spaces of community for Black people’ – an interview with Tracian Meikle

Being an expert on memorial murals in Kingston (Jamaica) Tracian Meikle came to Amsterdam to study how art can help to learn about the socio-economic and political tensions within a city. It is still a crucial element in her academic, curatorial and educational work. In a new series of interviews on PhD-research and its researchers Marsha Bruinen talks to Meikle about the mechanisms of exclusion she aims to unsettle, and the communal spaces she aims to create.

In 2014 you moved from Jamaica to the Netherlands to pursue a PhD at the University of Amsterdam which looked into the socio-political work of street art in Kingston, capital of Jamaica. Can you introduce this research a bit?

‘The PhD programme was presented by professor of Cities, Politics and Culture, Rivke Jaffe as a research into thinking about donmanship in Jamaica – and how art could possibly be a legitimation of that kind of leadership. In Jamaica, “donmanship” refers to an informal leadership of “dons” who take care of their communities and have political ties. It tends to come with violence or illegal activity, and is therefore typically characterized as a criminal kind of leadership.’

How did street-art enter your research?

‘I researched murals that memorialize people who are dead – a tradition that goes back in history to the 70s and that is strongly tied to the street art tradition of portraiture. Even though anyone can ask an artist to make a mural of their relative or friend, most memorial murals started off as a homage for dons; as a way to honor their leadership after their death. I entered my PhD asking if these murals offer a different kind of legitimation of dons. Dons are legitimized because they give money, because they provide justice and protect the community. But seeing people celebrated in this aesthetic realm can also be a way of legitimating them.’

Where would you find these murals?

‘They are typically painted in semi-public space, I say ‘semi’ because they are painted within neighbourhoods; if you don’t come in you don’t see it. In that sense it is different from what you might immediately visualize as ‘street-art’: it is not necessarily meant to be on the most visible spheres aiming to reach the biggest audience possible. They are for those who know about the person, cared about the person or know this person’s impact. Within these neighbourhoods the portraits can be painted on different surfaces. It could be on the perimeter walls that are around the house of where the person lived, on a central square, or even on concrete structures specifically erected for it. For my anthropological research I went into one neighbourhood in Kingston to talk with residents about what these murals meant for them. I wanted to find out what the work of such a mural was: what does it mean to the community? Along the way I expended my research and became interested in questions like: How can we think of the celebration of persons who are by some people seen as criminals? How does this reveal different socio-economic division in the city? How is this kind of street-art embedded in a wider street art scene in Kingston?’

I wanted to find out what the work of such a mural was: what does it mean to the community?

Left: Tracian Meikle presenting a paper on 'Iconization of Donmanship in Visual Culture in Kingston, Jamaica'. Photo: Lucy Evans. Right: Memorial Mural, Kingston, Jamaica. Photo: Tracian Meikle

Memorial Mural, Kingston, Jamaica. Photo: Tracian Meikle

Meikle tells me about a large street-art project that took place in Kingston in 2014. ‘Whereas memorial murals are often painted over by the police because they would encourage persons to look up to dons and thus to a life of crime – these contemporary, cool mainstream works were thought to beautify the neighbourhood’, she says. In one of the papers she published [1]. Meikle goes against the idea that such a simple distinction between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ murals can be drawn. She refers to what she calls a ‘‘multivalency’’ of memorial murals: even though memorial murals, she writes, do have the reputation of celebrating dons, they ‘not only portray and celebrate extra-state leadership and the values that outsiders associate with donmanship, such as a proclivity to violent justice’. They can also commemorate people who died in accidents, important members of the community and even policemen. This ‘multivalency of the murals reveals a hybridity of value systems that troubles the separation of the ghetto and this popular cultural practice from middle-class Jamaican values, and blurs the binary lens through which memorial murals are often viewed.’

Facing this upcoming street-art, what do you think the future of memorial murals will be?

‘I think they have been quite resilient – in the inner-city neighbourhood in uptown Kingston where I did my research the police didn’t paint the murals out. They did paint a lot of them out in downtown Kingston, notorious for being a place of conflict. But even there artists found different ways of keeping the practice going – painting in alleyways, directly on tombstones or on canvasses, making it able to move them around and activate them at dances and memorials. Again, it is important to emphasize that these portraits are not only of dons; they are also of every-day people.’

'Inspired by Katherine McKittrick’s Black Geographies and the intersection between space and race she outlines in that book, I wondered: how can you think of racialized bodies in space? How do they use this space, are they free in this space?'

Was it during your PhD that you got involved in other kinds of projects already?

‘A number of things lead the trajectory. My PhD broadly became a way of thinking about the politics of art in urban space– how do people react to it? Can you use art as well to learn about socio-economic and political tensions within a city? And, inspired by Katherine McKittrick’s Black Geographies and the intersection between space and race she outlines in that book – how can you think of racialized bodies in space? How do they use this space, are they free in this space? With these questions in mind, I started to organize and moderate talks in the city and became more directly involved with art and culture programs. One example is an artist residency I co-organized with Francesco Colona where we invited Neo Musangi, an artist from Kenya who looked at Zwarte Piet and the South-African relation to Holland.’ I bring these paths together under my creative platform – Balmyard. I also co-founded Amsterdam Black Women Collective in 2015. It started off as a way to bring Black women together in the city, to create a place where you could breathe, relax and find strength in each other in the face of dealing with the everyday experience of being a black person in Amsterdam. The collective is actually broader now – we have chapters in other cities in the Netherlands as well, and have relaunched as Netherlands Black Women!

Demo was the first time you directly collaborated with an artist on a project in public space, can you tell me some more about it?

‘I collaborated with artist Rosa Sijben on a project she did as part of the GET LOST- art route, which emerged from thinking about the lack of visibility of Black bodies in the city. We showed different Black skin-colors on billboards in Amsterdam South; these billboards functioned in a way as stand-ins for Black bodies – together they formed a kind of protest that could not be stopped by the police. Afterwards, I started having conversations with organizers of GET LOST and became involved in the curatorial team of the next iteration. Again this interest in urban space and in the question of how urban space can be used was important to me. What does this urban space mean for different dwellers of that space and how can art have an impact?’

'Demo II', 2018/2019, performance and installation by Rosa Sijben in collaboration with Tracian Meikle (Amsterdam Black Women collective)

'Demo II', 2018/2019, performance and installation by Rosa Sijben in collaboration with Tracian Meikle (Amsterdam Black Women collective)

From what I hear, pursuing PhD’s can be quite a solitary experience. Were these collaborations also a way to get out of that process?

‘I think working on a PhD can be a quite lonely, individual process – but I think that is part of writing in general, unless you find other ways to do it. Doing more collaborative work even within writing is something that could be worked on, I think. But I must say my supervisor did a good job of creating small PhD community: there were six of us with her and we had reading groups and peer reviews. My involvement in the city was more related to my Blackness and my need to connect outside of the university that was quite white, and not so much from the need for an intellectual community.’

It seems that you slowly started to become more interested in the artistic, more curatorial and ‘practical’ side of the questions on the politics of art in urban space you raised in your PhD. Is that true?

‘Very much so. I also became interested in the intersection between artistic and intellectual work. For me, artistic work is inherently intellectual. I think that there are many ways in which a division is suggested – supposing academic work to be more cerebral than artistic work. But I find art to be highly cerebral. I became interested in thinking about how I could become more involved in having discussions around art itself, not necessarily within academic realm. Going to exhibitions and having talks, I found the intellectual situation I needed. Additionally, I must say I am much more interested in talking than I am in writing. I think it is important to elevate talk as well in academia, where written work is very much elevated. A lot can be gained through conversation. All this also led to me becoming more interested in the freedom of art education versus traditional university education, which is why I started working more within art schools.’

'I must say I am much more interested in talking than I am in writing. I think it is important to elevate talk as well in academia, where written work is very much elevated. A lot can be gained through conversation'

Tracian Meikle during 'The Weekend of Global Cultures', Hiphop Museum, December 2017, Tropenmuseum, photo Kirsten Santen (thanks to Dutch National Museum of World Cultures)

Could you give some examples of such a programme? In what sense do they allow for more freedom in teaching?

‘I teach a class on dancehall and hip-hop at SNDO (School for New Dance Development) with Simone Zeefuik, and I also taught in the Honours programme of ArtEZ. In my classes there, I focused on looking at the personal as political. We talked about what it means to do political art and how you can see your art as being political even if it is quite personal. I wanted to let the students see that they are always in context and hence always linked to political issues. What I did for their assessments is to have them make an Instagram-account. I wanted them to recognize the amount of information such an account carries, and realize that it can function as a ‘‘super-short-essay’’. It was a way of saying: ‘‘hey, you do this work all the time, now let’s bring it into the classroom’’.’

You are also the coordinator of the Unsettling-programme at Sandberg and Rietveld. The publication of the NRC-article on Julian Andeweg in the beginning of November triggered virtually every Dutch art academy to unsettle, but this programme was initiated a few years earlier already. Can you tell me about your involvement there? What are the common roots you think are problematic and need unsettling?

‘I am super happy to be a part of this programme and happy as well that both Rietveld and Sandberg have indeed been a few steps ahead of other schools because of the fact that Unsettling started a few years back when issues in relation to racial discrimination came to the fore. In 2018, Clare Butcher and Judith Leysner were asked by the board to write a policy on inclusion and diversity, so on behalf of the board, Judith and Clare came up with the whole structure and name of Unsettling to truly include all voices and bodies within the school. I joined the programme in 2019 and have been working with Judith on ensuring that the mandate of Unsettling is carried out.

The programme sets out to make these art schools ‘radically inclusive’ – what does this mean?

‘It means thinking about how both Sandberg Instituut and the Gerrit Rietveld Academie can be schools that really reflect the kind of space that the city is. How can they be places that actually welcome the different bodies and ideas that are represented in Amsterdam, and the world more broadly? These questions raise other ones, like what is the right kind of curriculum? How can we have a more diverse teacher and student body? What does true social justice look like at the institution? For our programme we invite artists and thinkers to come in and give talks and workshops, but we also work directly with departments and the board in activating structural change with the Unsettling Framework for Action We work on issues such as discrimination, undesirable behaviour and harassment, and put in structures that can truly support the students. Next to that we also work with unions, such as the Black Student Union (which Judith Leysner and Nagare Willemsen set up in 2017), The Asian Union, The Latin American Caribbean Union, and the Near East Union. We are there for all students to come in and talk to us when we have our Unsettling stations on Thursday (and now via Zoom). That is what radical inclusion means: to be both broad and deep in ensuring that all persons can be nurtured, free and included in the school.’

'This is what radical inclusion means: to be both broad and deep in ensuring that all persons can be nurtured, free and included in the school'

‘I came here to be free’. Video installation at Pakhuis de Zwijger by performance artist Neo Musangi, curated by Tracian Meikle and Francesco Colona. Photo: Carolina Maurity-Frossard

I came here to be Free’. Panel discussion moderated by Tracian Meikle, with Neo Musangi, Timothy Aarons and Naomi van Stapele. Photo: Carolina Maurity-Frossard

What are your future plans? What would you be excited to see or participate in?

‘It is important for me to create a community for Black people in whatever form. In Amsterdam, and because of my interest in art, I want to create it around art. There is a lot going on already with different initiatives and I am happy to be connected to those, but I feel that there is always so much space for even more. Currently I am working with Marly Pierre Louis on ‘The Wild’. It will be a physical space that brings together Black literature and art, and we will organize talks and exhibitions as well, emphasizing what it means to be Black and free. We have already started with a pop-up last October and will have another this year. I want to generate spaces of belonging for the black community, focusing on the liberating power of our creativity and togetherness. That is my dream.’

[1] Tracian Meikle (2020) The Multivalency of Memorial Murals in Kingston, Jamaica: A Photo-Essay, Interventions, 22:1, 106-115, DOI: 10.1080/1369801X.2019.1659163.

Marsha Bruinen

is webredacteur bij Metropolis M