Pitchaya Ngamcharoen, performance ‘Who Moves and Who Doesn’t’ (2018), photo Lucie Draai

Absent scents – in conversation with Pitchaya Ngamcharoen and Sanne Vaassen

When people talk about smell they often emphasize its ability to trigger our memory. Specific smells take us back to our childhood, our grandparents’ home or the clothes of our exes. Olfactory artists Pitchaya Ngamcharoen and Sanne Vaassen both seem to go a step further by showing that memory of smell exceeds the mere personal. Smells trace back in time. They are part of our cultural memory, and as such, they (dis)orientate us.

Sanne was invited by Marres to design a walk of scents through the centre and outskirts of Maastricht, attempting to evoke the past of that city. In search of lost time was partly inspired on an earlier walk she designed in collaboration with the Natural History Museum of Maastricht. At that time, she pointed participants to the way in which the city is built on, but also with history. Some of the buildings people would pass by are built with 65 million year old limestone and marl, Sanne tells us.

Her walk of scents was a walk through history as well: ‘If you smell something you are brought back to a certain time and period; a scent is always linked to a specific location. Letting people smell certain things is a way to combine one’s own memories with our shared history.’ On different spots in and around the city participants are asked to imagine smells. Smells that were at some moment in time introduced, like the smell of cherries that was brought to the city during the Roman empire. Or smells that have disappeared, like the smell of leather production in the city. Sanne explains: ‘In Maastricht there used to be a tannery: a place where leather was washed and produced. In that process, human urine was used, and this would produce a smell that went all through the city of Maastricht.’ Another example she gives is the smell of horses– this smell has largely disappeared within western cities. In its place came the smell of cars.

Today certain smells are disappearing as well, Sanne continues: ‘As smaller shops disappear due to globalization, their smells are disappearing as well. The specific metal smell of hardware shops, for instance. Or the smell of cigarettes in public places.’

[blockquote]‘If you smell something you are brought back to a certain time and period; a scent is always linked to a specific location’

Sanne Vaassen, from 'In Search Of Lost Time'

Sanne Vaassen, from 'In Search Of Lost Time'

Sanne Vaassen, from 'In Search Of Lost Time'

[question Marsha Bruinen] Pitchaya, you write about, and work with, smell in connection to walking through the city and orienting yourself as well. One disappearing smell that had an influence on you was the disappearing smell of a noodle shop. Can you tell us a little bit about it?

‘There was a noodle shop that I always used to go to. At one moment, it wasn’t there anymore: it moved to another location. Accidentally, I found my way to this new location by following the smell of the noodle soup. That was the first moment I realised how much I need smell to orient myself, and how disoriented I feel when I do not have this device. Here Sara Ahmed’s notion of orientation in Queer Phenomenology is inspiring to me. Even though Ahmed focuses more on sexual orientation, what inspires me is that she always sees orientation of oneself as orientation in relation to others, whether these ‘‘others’’ are people or surroundings. It connects a bit with what Sanne just said. A smell is produced in a specific time and place and helps you know where you stand and what is around you. In the case of the relocated noodle shop, the smell had changed, because the surroundings of the shop changed. Now there were trees blooming on top of it, for example. This new situation, I thought, could be considered as a collection of different smells, a perfume. If one element of a perfume is different, the smell of the perfume as a whole becomes completely different.’

‘Yes, and that also depends on the person, right? Since my body smell is different than yours, any perfume would smell differently on mine than on yours.’

[question Marsha Bruinen] A few months ago a friend of mine lost her sense of smell. She told me that she realised that if there would be a fire in her house, she wouldn’t be able to smell it. Smell, in that case, was very clearly exposed as (an unconscious) tool for orientation. We use it to determine what is safe, and what is dangerous. But also to say: ‘this smells nice’ and ‘this stinks’. Through memory, we can also recall which smells are familiar and which are unfamiliar, and we can start to distinguish between ‘own’ and ‘other’ smells. Pitchaya, I know you have thought about these things a lot. One thing that intrigued me when I was reading your DAI-graduation thesis was your idea of ‘deodorization as colonization’. Can you tell us more about this?

‘There are a few ideas I’m trying to unpack with that notion. The first is the ability to get used to the smell of your own environment. One easily gets used to the smell of their own surroundings. And whereas someone might not recognize their own smell, or even that they smell, it is without any effort that one recognizes someone else’s smell. Secondly, and connected to that, there is the idea that being ‘‘clean’’, being the clean body, the body that uses perfume or fragrance, is somehow better. And next to that body, the ‘‘foul’’ body is easily discriminated. Notions of cleanliness and scent are therefore related to class. Discrimination can come forward in personal interactions, but it can also be systematic. If you are from some part of the world and you are moving to another country, it might be more difficult for you to rent a house because of a concern that the smell of your food will stay in the house after you leave. But to force someone to be ‘‘clean’’, to force someone to erase their smell, is a way of denying the being of that person and culture. Their very existence is denied, unless they manage to appear in more acceptable presence – unless they adapt to the normalized smell.’

'To force someone to be ‘‘clean’’, to force someone to erase their smell, is a way of denying the being of that person and culture'

Pitchaya Ngamcharoen, performance 'Traces', photo Sanne Kabalt

Pitchaya Ngamcharoen, performance 'Traces', photo Sanne Kabalt

‘That idea of the erasure of smell makes me think of an article I recently read, on a whole different topic. It was about the importance of scent in ‘‘finding your match’’: it showed that people that like each other’s smells tend to stay together for a longer time. I found this interesting: putting on perfumes for dates we are actually covering up the smell that is so important in communicating with someone new.’

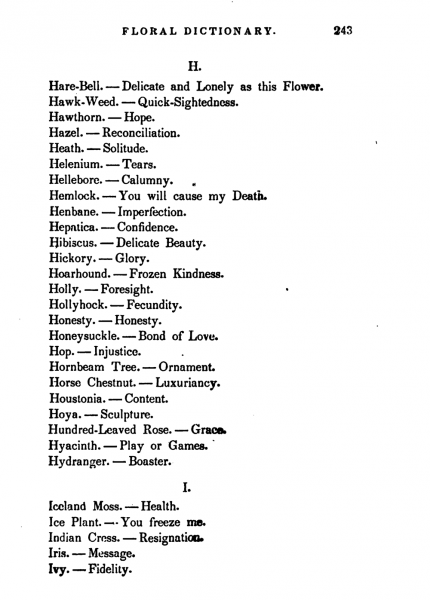

‘Verbloemen’ is the title Sanne gave to one of her works. The title is difficult to translate into English, but means something like ‘covering up’, making something appear nicer than it truly is by covering it with flowers, so to say. For this work, Sanne dived into floriography: a kind of language used during Victoran ages to send out messages through flowers.

‘People wouldn’t say ‘‘I like you’’, but would send a bouquet with flowers that said it for them. Every flower had a different meaning; in a dictionary flowers were listed and linked with specific words. These meanings that were attributed to flowers were very specific. It would go beyond stating red roses as a symbol for love. Even though we still continue with some of these floral traditions – we recognize that some flowers aren’t appropriate for funerals, and that some are better for birthdays- most of the meanings are lost on us. It is a lost language. I wondered: what are the important messages we send out today? That’s when I started looking into political speeches and translating them into perfumes. It is an on-going project: I have now translated six speeches into perfumes. The first was Trump’s Inauguration Speech. I analysed this speech, looked up the words it contained and found the plants and flowers these relate to in these dictionaries. Then I put these flowers together with essential oils and created a perfume. It smelled a bit like mosquito spray.’

'I analysed Trumps' Inauguration Speech into a perfume. It smelled a bit like mosquito spray’

Floral dictionary

Sanne Vaassen, 'Verbloemen'/'Nosegay', Hassan Diab Resignation

Sanne Vaassen, 'Verbloemen'/'Nosegay', Narendra Modi - Dear Soldiers

‘The dictionary sounds very interesting. It makes me think of how you can communicate a negative message, a message that someone doesn’t want to hear, with flowers that are all lovely and nice.’

‘Exactly. One rose in the list has as its meaning: ‘‘beauty is your only attraction’’. Such a painful rose to receive!’

‘It’s also interesting that a floral dictionary of another culture would be quite different. If you want to communicate in a different country, flowers will have different meanings, so the same message would smell differently elsewhere.’

Sanne’s work makes me think of an article this website recently published by Laurie Cluitmans called ‘Total Landscaping’. Cluitmans argued that gardening, something many people started doing again during the first lockdown, cannot be seen as an innocent hobby anymore. Having a garden means having a territory: it means making decisions on which flowers to include and which to exclude. Interestingly, this idea of building and controlling your territory comes forward in Verbloemen as well: the political speeches and the floral dictionaries are brought together as different worlds that stem from a similar need to control.

Up till now we’ve mostly talked about smell as a method of discrimination. Your works show that smell can also be a way to bridge, rather than to divide. Perhaps more so with smells than with visuals, we realize that we often perceive many things at once. Inhaling a smell in that sense means inhaling a mixture of smells. Pitchaya, I was watching documentation of Who Moves and Who Doesn’t, a performance by you at State of Concept in Athens, and in that performance this idea of interchanging smells seemed to play a role. Different smells were generated at once: the audience was sitting in a mixture of smells. Can you tell us a bit about this work?

‘The title of the work is a quote from a book from Danielle Goldman, in which Goldman writes about improvisation dance. In this performance I am performing my daily routine: I start the day by lighting up the stove, cooking breakfast, smoking a little bit, preparing my clothes and putting the scent of flowered water on me –a ritual that reminds me of family in Thailand. I continue creating different smells in one space, such as the smell of cooling powder we use in Thailand to cool our bodies. There are also other stations in the same space, in which performers are burning myrrh. The audience is moving around in the space and the performers are as well. In close proximity to each other, they are also putting the smell produced by other performers on their bodies. A lot of these gestures symbolize being one: a kind of togetherness that entails sharing the same smell.’

'A lot of these gestures symbolize being one: a kind of togetherness that entails sharing the same smell'

Pitchaya Ngamcharoen, performance 'Who Moves and Who Doesn't' (2018), photo Sanne Kabalt

[question Marsha Bruinen] At some point, the performers also start cleaning their bodies and the space.

‘Yes, that is an important part of the performance. Reaching the end of the performance, the smells are being erased and are replaced with more synthetic smells: the smells used to cover smells we don’t like. This idea of erasing smell is also present in the fans that are spinning in the space to manage the air. Finally, the performers use mobs to wipe the floor.’

This makes me think of your notion of ‘common scents’, can you tell me a bit about it?

‘Most of my work is based on belief that many worlds can coexist together in same space. For me, that is the link between improvisation dance. When people move around, a dance of bodies and smells occurs. As one person moves, it leaves traces of movement by leaving its body smell. Sharing a space can be seen as having many lines of smell intertwine in the same space. Who Moves and Who Doesn’t is basically a visualisation of that idea.’

Pitchaya Ngamcharoen, performance 'Who Moves and Who Doesn't' (2018), photo Agata Cieślak

Pitchaya Ngamcharoen, performance 'Who Moves and Who Doesn't' (2018), photo Alah Abu Asad

I am curious about how some of the things we talked about– smell as memory, as a way of distinction or as a potential bridge- align with the idea of smell as something fleeting. How does this fleeting nature of smell find its place in your art-practices? Pitchaya, you work mainly with time-based performances. Was this a conscious decision in relation to the time-based character of smell?

‘It is indeed a conscious decision that I don’t want the smell to be captured. That is what I love about the nature of smell: it is ephemeral, but also evidential. What I try to offer is an experience in space and time.’

‘I find this ungraspability and invisibility very important as well. I also think that sometimes it is better to imagine something than knowing something.’

[question Marsha Bruinen] If there is a tension in documenting a work of smell, this is not a problem since it could actually emphasize what your work tries to bring across?

‘Exactly.’

[question Marsha Bruinen] In light of all this, it is interesting but also a bit weird to have a zoom conversation in which we cannot smell each other. Has covid shed new light on your thoughts about smell?

[answer Sanne Vaassen] ‘I think that covid makes visible what is so interesting about smell to me: that it is a way of communicating. When you smell someone you communicate with someone; without it, a part of the conversation is gone.’

'Covid makes visible what is so interesting about smell to me: that smell is a way of communicating. When you smell someone you communicate with someone; without it, a part of the conversation is gone’

‘And it’s not only lost in zoom conversations like these. Now that we have to be at least 1,5 m apart form each other, there is a certain proximity and smell we cannot have. Before, when someone would move close to you, there would be a touch of air that could really hit you. Now that’s gone. I also realised again another thing. When the lockdown just started, barely anyone was out on the street. When people slowly started to go out more and more again, during summer, I was cycling my usual route through the city. What I realised is that the same path didn’t at all feel the same. Now that there was little traffic, a lot of elements that contributed to the former smell of that route had disappeared. I think this shows that an experience of space is not just determined by a location that can be pinpointed on a map. It has to do with the specific time and season, and with the smells of those who live there and the things that are done there.’

Sanne Vaassen’s work will be on show in In search of Sharawadgi, an exhibition at Schunk in Heerlen, that aims to open on the 2nd of May.

Marsha Bruinen

is webredacteur bij Metropolis M