‘Corpus’

Precarious schemes – On Brianna Leatherbury’s Liquidation series

At the beginning of the renovation works Hartwig Art Foundation recently started in the former courthouse at the Parnassusweg in Amsterdam, Mitchell Thar reflects on Brianna Leatherbury’s videowork Liquidation, tracing the often absurd real estate schemes that shape the narratives of our monumental buildings. For example this courthouse (soon to be a museum), a former prison in Utrecht (soon to be workspaces and a hotel), and a farm estate in Groningen (soon to be Airbnb).

The former sub-district courthouse of Parnassusweg 200 opened in 1975 and was designed by architect Ben Loerakker. The main building consists of seven stories and four courtrooms, to which extensions have later been added, most of which have been demolished in recent years to make way for a judicial complex. Since 2013, the main building has transitioned into a protected monument. Recently, different spaces in the building have been rented out to start-ups and artist initiatives under temporary anti-squat contracts in the building. This is a precarious scheme familiar to anyone working in the cultural field in the Netherlands. Currently, the building is being rehabilitated into a so-called ‘creative hub’, including a contemporary art museum and artist studios, by the Hartwig Art Foundation.

Such strange and inconsistent carousels of functions, from institutional to interim space, back to institution again, are the subject of Brianna Leatherbury’s Liquidation (2020-), an ongoing series of videos presented in site-specific installations in which viewers are presented with a tour of different properties. Each video documents a building that was or is currently put on auction by the Dutch government in an ‘uncertain moment of operation’, as the artist tells me.[1] Leatherbury describes these works as ‘material testimonies’ towards an ‘architectural and historical conflict at play in this real-estate scheme’. The properties referred to are sold off by the state to the highest bidder, even though some of them have been assigned a monumental status which protects them from demolition and assures that they can only be changed to a certain degree.

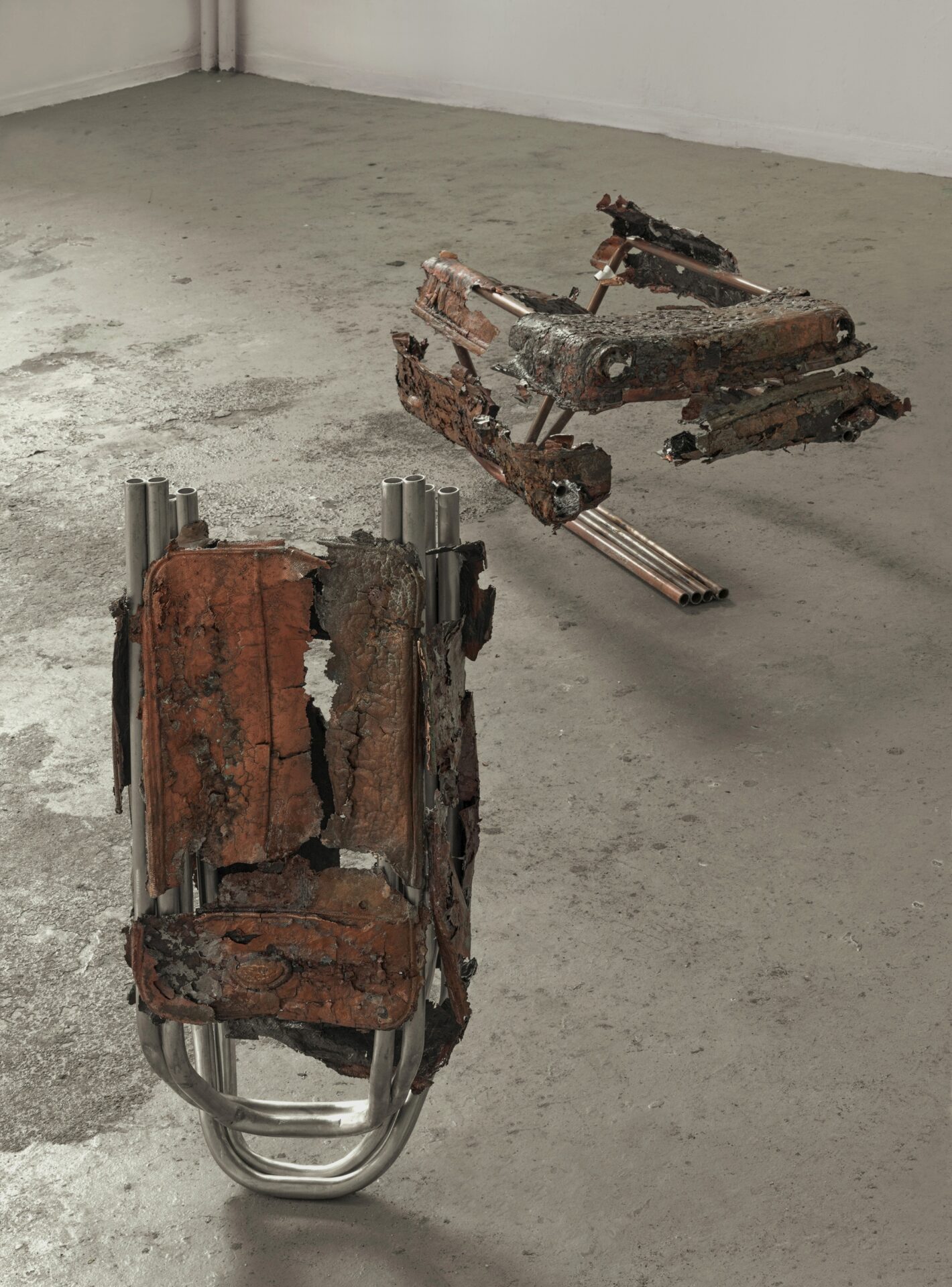

'Corpus', exhibition view at bologna.cc, Amsterdam, 2023, courtesy of the artist

The properties referred to are sold off by the state to the highest bidder, even though some of them have been assigned a monumental status which protects them from demolition and assures that they can only be changed to a certain degree

'Corpus', exhibition view at bologna.cc, Amsterdam, 2023, courtesy of the artist

Two works from the Liquidation series were recently shown at bologna.cc, in its temporary space at the former courthouse in Amsterdam-Zuid. Documenting the movement towards renovation, Leatherbury’s series captures the precarious moment when the buildings are covered up by other schemes. In Leatherbury’s words: ‘It’s clear from this [real-estate] scheme that [the occupants] may easily substitute one another, no matter what the architecture calls for.’ Following the notice of eviction for bologna.cc and all other tenants and anti-squatters of the former courthouse on Parnassusweg 200, the work was presented in the midst of the move, rendering its message all the more urgent.

The bologna.cc project space was located a few stories up in the courthouse, surrounded by spaces out of use. Visitors to the Corpus exhibition were led to a room with two of Leatherbury’s video works: Why should we keep these buildings?, presented on a tablet in front of a window, resting on a stand which resembled a podium, and L1quidation (both from 2022). Central to the exhibition, L1quidation was a video projection which split the room in half, viewable from both sides of the projection screen, and positioned for the viewer to move around in the near-empty space of the courthouse room. The space was dimly lit by the video works only, as the windows had been meshed for the presentation – replacing their transparency with muted shadows of the backdrop of the Zuidas financial district.

In the exhibition text for Corpus, written by Alec Mateo, the two properties in the videos are identified as the former Wolvenplein prison in Utrecht, which has been out of operation as a penitentiary institution since 2015, and a bankrupted farm estate in Groningen. Both properties have recently been auctioned online by the Rijksvastgoedbedrijf (RVB), the largest real estate company in the Netherlands, owned by the state.

No longer a responsibility of the state once they have been sold, the properties have since taken on multiple functions. In the case of the prison, this function is a cultural broedplaats with start-ups, artists and freelancers renting the empty prison cells on temporary contracts until its planned, but to be seen, conversion into housing (both social- and middlepriced), artist studios and office spaces. The farm estate – which went bankrupt after one hundred years, partly in consequence to the rise of automated agriculture in the Netherlands – after a period of being vacant and squatted, was used as a lucrative but illegal cannabis nursery before being shut down in the early 2000s and bequeathed to the RVB. At present, it houses a bed and breakfast.

Leatherbury describes the properties featured in L1quidation in terms of identity and memory: ‘In the case of the buildings in L1quidation, both properties are monuments and can only be physically changed so much. But narratively, functionally, they are allowed to take on a new identity. This scheme brought to mind architectural renderings – buildings without humans, or with bodies digitally placed in at the end, scriptedly enjoying the space. In this way, I’m also curious about national/social memory: what will we think of prisons when they are all hotels or office spaces in fifty years? Where will we be living?’

'L1quidation', 2022, video still, courtesy of the artist

Leatherbury installed a humidifier in both of L1quidation’s protagonist buildings and filmed it in use, spraying not water as usual, but lab-material artificial sweat

The video resists stylization, yet incorporates elements of horror and DIY-documentary film, without actually being a documentary. Therefore, it finds itself in a nervous, liminal state that aptly mirrors the spaces of its recording. Voice-overs from the buildings’ caregivers give testimony to their former use as well their often long and extended transitional moments. The voice-overs are bridged by sequences of appropriated footage: automated farming, followed by high-rises sourced from the same company redeveloping the prison, AM. Subtitled with contradicting sentiments such as ‘A place that’s bold, healthy, sustainable/Where you never want to go home’, they vent an all too familiar state of affairs, grounded in the extraction of affect in the service of productivity.

Leatherbury installed a humidifier in both of L1quidation’s protagonist buildings and filmed it in use, spraying not water as usual, but lab-material artificial sweat. The installed humidifier-sculpture forms the impetus that leads the video away from documentation of a site-specific work to a site-specific video installation. Reused in the work’s presentation, the humidifier, built with industrial greenhouse equipment, was reappropriated as the carrier for the video projection in the courthouse and in other showings of this work. Fabricated with plastic hoses, high pressure misting nozzles and steel tubes, the humidifiers’ presence in the video work and as the infrastructure for the projection as a semi-translucent screen materializes disappearance.

As explained by Leatherbury, the installation ‘was an attempt to confer all of these sweats together – the sweat of the prisoners who once inhabited these cells, the sweat of the freelancer who pays to work in them, and the sweat of the future hotel guests (and the same can be said about the farmhouse: the former owners, the animals, the squatter, the future airbnb guests).’

The humidifier thus becomes the protagonist of the video, its perspiration dampening the buildings’ infrastructure. Leatherbury writes that ‘it’s not a coincidence that all of the materials used – the humidifier, the fake sweat, the real estate – share both an artificial and an industrial quality. They also define an indirect transient relationship to human consumption that I think is specific to our current economic and political terrain.’ Consequently, the work questions what happens to the site when it is (again) devoid of human bodies, when attention has been directed elsewhere or the property is refurbished: what are these spaces without bodies, and what does their preservation represent for the culture at large? Leatherbury pinpoints a strange paradox which documents an even stranger case of priorities: site-specificity here is no less virtual than actual.

Negative totems

The other shorter, interrelated video, titled Why should we keep these buildings? (2022), is also from the Liquidation series. Before it was shown at bologna.cc, this video also featured at Festival Media Mediterranea, ECPD (Pula, HR). Made with a freeware 3D-scanning app, the video is voiced-over by the current owner of the farm estate as the phone-scanner intermittently takes coordinates of both the prison and the farmhouse, creating a rendering of the buildings under transition. The 3D-model results of the scanning are not shown: the buildings’ virtuality is again underscored by the process of documentation between what they are memorialized to be and what they are slated, speculated to become.

Video still from 'Why should we keep these buildings?', 00:01:43, 2022, courtesy of the artist

As Mateo explains in the exhibition text, Corpus enacts the prospector of today: the explorer who is mining not for minerals but for speculation. A point of reference for Leatherbury across multiple bodies of work, their slightly earlier set of sculptures from 2021, Insider’s Grave, plays a game of mirror with the spectator. The starting point for this work were objects borrowed out by stock-market investors in response to the question: ‘What is an object that you would take to your grave?’ Leatherbury plated these objects in a thin copper shell – the skins of this process became the sculpture, after the original objects were returned to the investors. The resulting, transactional sculptures are something like negative totems, evacuated of meaning yet memorialized in a slow process of oxidation. In tandem, the desolate burns of Leatherbury’s material testimonies in Insider’s Grave and the Liquidation series probe the machinery behind a false semblance: where facade compensates function – as priorities, like artificial sweat, disappear into thin air.

In 2021, Leatherbury presented another series of site-specific sculptures at De Ateliers Offspring titled Incoming. Using rotary lasers to first make contact with their neighbors, Leatherbury then beamed from the private apartments of the neighbors into their own studio and throughout the institution. The rotary laser, which is used in urban development and land surveying, thereby made ‘a connection between two (potentially) temporary neighbors’, connecting them in the acknowledgement that their street has dramatically changed over the past thirty years. The question of what changes in the neighborhood, and at whose expense, occupied the work. Framing what are often inaccessible movements of change or ‘development’, the space between private to public is made visual in Incoming, like it is similarly done in Liquidation: the viewer is left with coordinates to consider these changes, and to weigh in whose benefit they are made for.

'Hard shelled stretch marks/I’m thinking of zeros of carbon footprints and bank accounts together with smiles. What do you think these cultural ventures teach your children?', copper platings of borrowed objects, aluminum, from the series 'Insider’s Grave', 2021: exhibition view De Ateliers, Amsterdam, 2021. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij

'Insider’s Grave', installation view at Snooperverse, HISK Gosset Site, Brussels, 2022, courtesy of the artist

Material testimonies

Just a move west along the A10 highway, another artwork in recent memory addresses the same real-estate scheme as Leatherbury, through similar methods of documentation. Wendelien van Oldenborgh’s film Prologue: Squat/Antisquat (2016), shot in the Tripolis complex: an office complex of three buildings designed by Aldo van Eyck in 1994, maintained under the same conditions as the buildings that Leatherbury documented – now in redevelopment, with offices being rented to Uber and a law firm, De Brauw Blackstone Westbroek[2] – only some 1.3 km away from the Parnassusweg 200 courthouse. In the essay which outlines the film’s interconnecting sites of struggle and emancipation in Amsterdam’s housing crisis, Asset as Film: Filmmaking in Relation to a Certain Realness of Site, van Oldenborgh writes:

Tripolis exists as a prime example of a contemporary, complex confluence of site, territory, and legality: an office workplace, a home to asylum-seekers, and a corporate asset. Its value goes up as long as one of these is excluded—edited out. As much as a method for canceling out, omitting, or excluding, filmic montage also provides an opportunity to structure and thereby question and affect the temporal thinking that supports those very exclusions.[3]

The exclusions that Van Oldenborgh underlines are those of the actions of We Are Here: a collective of asylum seekers denied official stay in the Netherlands, unable to return to their countries of origin or to go anywhere else, who, temporarily but successfully, squatted the Tripolis 200 for roughly three weeks in 2016 – before being informed to the city authorities by a group of anti-squatters in Tripolis 300.[4] Until two years before, the building itself was a municipal office for Amsterdam-Zuid – an office to register permits of residence, marriage and official documents.[5] The absurdity of this scheme is shared in both Leatherbury and van Oldenborgh’s accounting of the filmed buildings’ uncertain state(s) of use: material testimonies which enact films’ ability to do just as van Oldenborgh proposed in restructuring what is often omitted from the official gaze. In the midst of a housing crisis, where prisons will become office space and courthouses are repurposed into art museums, recordings such as these are revealing – if not cautionary.

[1] Citations taken from an e-mail correspondence with Leatherbury. All quotations in this text have been taken from there or from the artist’s website.

[2] https://zuidas.nl/project/tripolis/

[3] Wendelien van Oldenborgh, “Asset as Set: Filmmaking in Relation to a Certain Realness of Site,” E-Flux, Issue 90 (April 2018) http://www.e-flux.com/journal/90/192148/asset-as-set-filmmaking-in-relation-

to-a-certain-realness-of-cite/ (accessed November 6, 2023)

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

For more information about bologna.cc, visit their website.

Mitchell Thar

is an artist / studies artistic research at UvA