Logo No Logo – A report on a visit to the 31st São Paulo Bienal

‘However, there is nothing inevitable in the relationship between the

violence of our age and the conflicts that might have caused it.

Conflict itself, an essential part of any agonistic system, can be a

tool to modify those sequences. It is to be welcomed, as a way to raise

the alarm, as a way to reveal, as a way to intervene.’

This provocation appears at the start of the guide to the 31st Sao Paulo Bienal – and quite a self-fulfilling prophecy it turned out to be. Co-curated by Van Abbemuseum director, Charles Esche, together with Galit Eilat, Nuria Enguita Mayo, Oren Sagiv and Pablo Lafuente, this edition of the second oldest biennial saw 81 projects converge upon the 30,000m2 pavilion designed by Oscar Neimeyer and Hélio Uchôa. Dogged by tensions over both backstage or infrastructural issues, and those concerning its more public contents, the Bienal entitled ‘How to […] things that don’t exist’ exposes just how much lies within that elliptical space between an exhibition’s conception and reception.

Constituted by a team known for their views on the political capacities of artistic practice and the art institution, it was with some surprise that many read the public statement issued by the artists, just days before the opening. This statement pertained to the non-transparent pooling of certain Bienal funds which endangered not only the positions, but in some cases, the personal safety, of some of the Bienal’s contributors.

Signed by an eventual total of 61 contributors, the prospect was one of withdrawal if a solution could not be reached concerning the representation of certain logos on sponsorship walls, publications and press material. (I say ‘certain logos’ as the issue of accepting sponsorship was directed chiefly toward that coming from the Israeli State and not those corporations whose ties to the Bienal are also a major concern for local artists.)

‘There’s no limit on visibility,’ says Galit Eilat, one of the curatorial team, in discussing the lack of policy surrounding corporate branding of the Bienal space. And despite the support shown by the curators for the artists’ right to express their consternation, their call seemed a somewhat more moderate one – asking for an awareness of the deep impact of cultural funding sources on the ‘supposedly “independent” curatorial and artistic narrative of an event.’

While the volume of this moment may have been muted somewhat by the proceeding internal discussion and addition of a vitally important sentence on the wall of sponsors (‘The institutions below only support the artists from their respective countries’), the issues raised by it, run deeper than a mere case of “logo” vs. “no logo”.

Having done away with national representation in the Bienal in Lisette Lagnado’s 2006 edition, the Bienal’s history is in fact steeped in the very conflict welcomed by this year’s thematic framing. In the late ‘60s and ‘70s, a number of famous examples emerge of artistic refusal to be subsumed by overarching categories and complicities. And though this history might overshadow the current exhibition, as well as many of the works therein which address the falseness of such polarities, it is in the perhaps anti-climatic moments of post-opening reality that one can see the everyday negotiate work of that interweaving, agonistic process.

Following the opening – which did in fact happen – a number of complaints (over 4000 to be precise) arrived at the Bienal’s PR desk concerning the appropriateness of some of the artworks for the Bienal’s student visitors. These visitors constitute a quarter of the Bienal’s million viewers. (That number needs to be read in the context of a city inhabited by more than ten times that amount.) The complaints pertained to specific projects with provocative titles – such as the collection display organised by Miguel A. López God is Queer (2014) – and subversive content, particularly relating to gender – as seen in Hudnilson Jr.’s xerox paradise Tension Zone (1980) – or a certain kind of violence – supposedly made explicit by Halil Altindere’s rapper video Wonderland (2013).

All of the above are flagged as “inappropriate” by a warning sign which appeared around the Bienal in the following weeks. An exclamation mark inside a triangle bids viewers under the age of 18 be advised by Law 8,069 of July 1990.

For the 250-member team of Bienal educators (known as the Educativo), this restriction ostensibly meant they might have had to cut short their tours with school groups substantially. However, due to the ongoing, dynamic conversation amongst themselves and a number of the artists in the Bienal (conducted in person and via a closed Facebook page), the Educativo have introduced what they’re calling the Proibido [prohibited] Tour.

On this route, student groups are, as usual, taken to all the works. However, when approaching a prohibited piece like Ines Doujak and John Barker’s Loomshuttles, Warpaths (2009-), whose poster series and objects trace the, often brutal, histories and presents of textile production processes in the Americas, the tour guide will send the group’s teacher in to see the installation and report back to the students what they found.

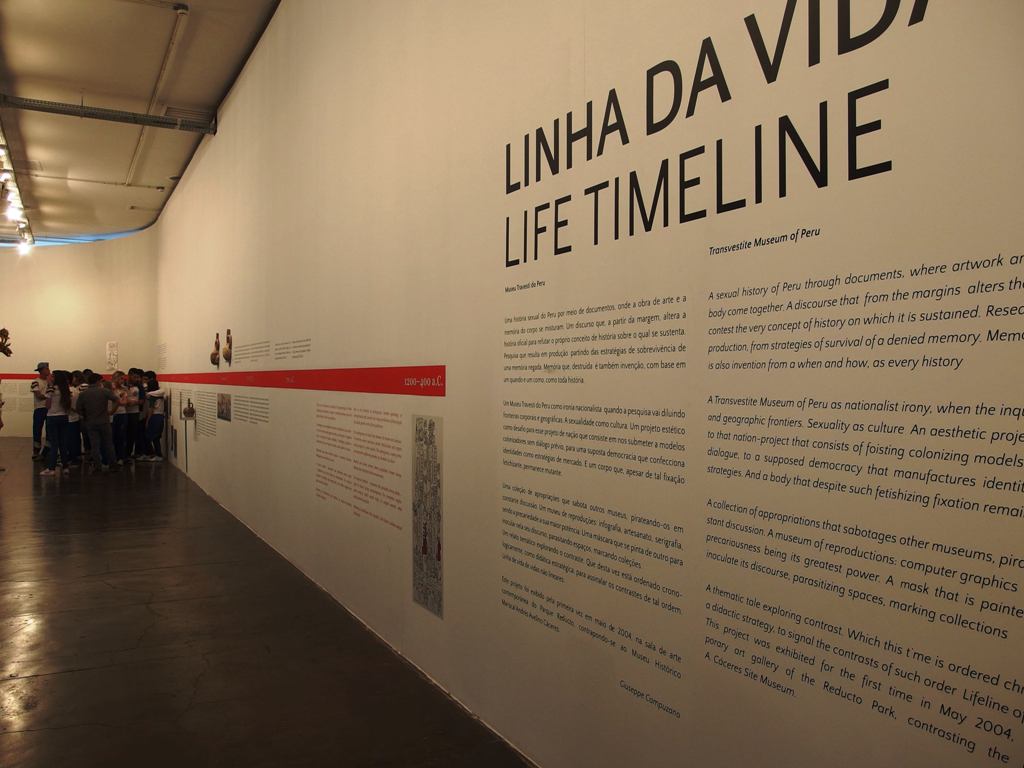

Another stop could be the iconoclastic antics of the Étcetera… collective in their absorbing antechamber of relics and phone conversations with the Almighty, entitled Errar de Dios [Erring from God] (2014). It could be the Línea de vida of the Transvestite Museum of Peru created by the late drag queen and philosopher Giuseppe Campuzano. Clara Ianni’s collaborative film with Mães de Maio – an organisation which seeks justice for mothers who have lost sons and daughters due to police violence in Brazil – would be another obvious point on the route. However, despite their potentially controversial content, these works have not been censored and the viewer is left to consider the superficial criteria on which the other prohibitions must have been based.

Other unrestricted but nonetheless critically insightful works include those by artists from closer to home. Jonas Staal’s planological pairing of two cities: one, the “airplane-shaped” Brasília and the other, Nosso Lar, believed by spiritists to hover over Rio de Janeiro, recalibrates the rationality of Brazil’s proud and problematic history of Modernism. Yael Bartana, whose Inferno (2013) was presented earlier this year at the Stedelijk Museum, also brings grand developmental schemes crashing to the ground with her melodramatic filmic fulfilment of the third destruction of Solomon’s Temple in São Paulo.

The geological research of Otobong Nkanga has developed throughout a number of performative and installation renditions in the last years elsewhere. Now Landversation (2014) finds a painfully poignant fit amidst the environmental urgencies of Brazilian corporate-induced climate change and land ownership. The oral modes invoked by her project are echoed in a number of other projects such as Mujawara (2014) a collaborative project initiated by collective Contrafilé together with Palestine-based Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti, which sought to bring both the Arabic tradition of neighbourliness (mujawara) and knowledge of the work done for rights amongst marginalised groups of Brazil’s landless workers, into the exhibition space.

While these endeavours speak to the transformative power of confrontation, when conflicting visions or versions of the world are juxtaposed in the the ‘[…]’ of the exhibition, they cannot, and in most cases do not, claim to completely escape the complicities and complications of an artpolitik entangled in a realpolitik. And perhaps this is the raising of the alarm spoken of in the exhibition guide – a siren which resounds throughout Niemeyer’s now not-so hallowed halls.

Clare Burcher is a curator and a critic

Bienal di Sao Paulo

6.9 – 7.12.2014

Clare Butcher